A new series of real-time online discussion groups using Skype begins from 21st Sept. This series will be led by Robert M Ellis, and based around the introductory book ‘Migglism’. Please see the Online Discussion Groups page for details, and submit the online form if you would like to participate.

All posts by Robert M Ellis

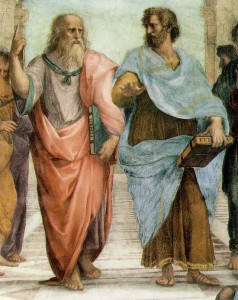

The quarrel between philosophy and poetry

‘”The part which relies on measurement and calculation must be the best part of us…. So is not the part which contradicts them an inferior one?”

“Inevitably”‘ (Plato’s Republic, 603a)

Thus does Plato provide the basic rationale for his condemnation of poetry, along with the other arts. He says that the works of the poet, like those of the artist, have “a low degree of truth” and “he deals with a low element of the mind”. “We are therefore quite right to refuse to admit him to a properly run state” continues Socrates, in pronouncements that are only echoed and accepted by others in the dialogue. Thus begins the long quarrel between philosophy and poetry.

It is easy to see this quarrel as reflecting that between those who judge solely on the basis of the representations of the left brain hemisphere at a particular time, and those who, using the right hemisphere, want to look beyond such certainties and integrate the contents of the left hemisphere at different times. Plato, through the mouthpiece of his dramatised Socrates, appears to reflect that left brain certainty: that rightness dwells only in the apparent clarity of our current representation, and in its tools of positive measurement, critical analysis, and planning. Humour, ambiguity, and grief should not be publicly shared in art, he says, but rather repressed and made objects of shame, made subject to the control of ‘reason’.

Fortunately, Plato’s ideal Republic of the left brain was never created in the fashion he envisaged it. However, he has had many imitators, particularly in the shape of political revolutionaries of a kind who wished to purge the world of all untidy ambiguity that did not fit their utopian vision. Rather than keeping them out of the Republic entirely, the Fascist and Communist regimes of the twentieth century subjected poets and other artists to censorship and control, so that they could only publicly express what fitted the party line.

Plato attacked poetry because he believed it was a form of rhetoric, which would stir up and manipulate uncontrolled emotions, but ironically it is philosophy that has too often become allied to rhetoric by offering naïve political schemes or supporting conventional views of the world, at odds with the immediacy of poetry. It is the poets who have generally understood rather better that meaning resides, not in representations, but in embodied experience. Language that does not speak to that experience appeals only to the shared lowest common denominator of human experience. Without poetry we are too often left to the clichés of the crowd and its groupthink, unable to summon creative responses to new conditions because the very tools of our thinking have been blunted by the platitudes of conventional certainty.

I have recently come across a quotation from the great Irish poet W.B. Yeats that gives wonderful expression to this poetic counter-attack:

“Ideas and images which have to be understood and loved by large numbers of people, must appeal to no rich personal experience, no patience of study, no delicacy of sense…. Manner and matter will be rhetorical, conventional, sentimental; and language, because it is carried beyond life perpetually, will be as wasted as the thought, with unmeaning pedantries and silences, and a dread of all that has salt and savour.” (from J.M.Synge and the Ireland of his time, 1910, quoted recently in a TLS article by Roy Foster)

Of course, philosophy is a varied thing, but if modern philosophy has a consistent theme (with only a few exceptions) it is the overwhelming dominance of limited, ‘flat’ left hemisphere thought in which the wider use of thinking in experience is completely ignored. In the case of Anglo-Saxon philosophy, it may be precise, analytic and highly technical, but nevertheless have the effect only of reinforcing conventional attitudes, or (in the case of post-modernism) it may be highly critical of all conventions, but again in a decontextualized way that gives no attention to the depth or breadth of experience or the practical context in which it is read. Whilst this kind of philosophy may seem of marginal interest to most people in modern society, that marginality might be seen as the unintended and ironic outcome of Plato’s approach. By relying entirely on an inadequate conception of ‘reason’, philosophy has made itself marginal. However, the conventionality, parochialism, cynicism and relativism that dominate it are shared with much of the rest of society.

Has either side ‘won’ the debate? On the one hand it seems that philosophy has ‘won’ in the sense that poetry is extremely marginal in our society, and superficial representationalism rules supreme. On the other hand, however, it seems that poetry has ‘won’, because it has not been banished from the state, and every new generation finds new ways of connecting with the imagination, however puritanical the public discourse. It is, of course, an unwinnable war and a delusory conflict, because both philosophy and poetry address central areas of human experience. Every time we machine-gun down the ‘opposition’, it is likely to pop up again, like an army of indestructible revenants.

It’s time for a new attempt at lasting peace negotiations. Part of a lasting solution, in my view, involves the deconstruction of the wrong assumptions on which the whole conflict has been based. No helpful philosophy can be assembled on the basis of a representational view of meaning that denies the body and its shaping effect on even the most abstract of our constructions. But if we begin with this recognition and face up to its revolutionary implications, philosophy can be shaped anew in a way that works in co-operation and peace with poetry. Metaphor is the way in which we appreciate meaning and connect it to bodily experience, not a dispensible ornament on a ‘literal’ base. Beliefs constructed on the assumption that they are even capable of reflecting reality become dogmatic, entrench us in inadequate attitudes, and create conflict. ‘Emotion’ is part of our basic response to the world, and is not ‘subjective’ and ripe for repression, but rather, like ‘reason’, part of our provisional account of the world, to be shaped with increasing adequacy.

Poets have been telling us about the power of metaphor and the need to face up to repressed ’emotion’, for thousands of years. Now it’s time to start listening, and to incorporate that view into a richer and more adequate kind of philosophy. I will close with a quote from Seamus Heaney (who died a year ago), which I also found in the same TLS article as the one from Yeats above:

“Within our individual selves we can reconcile two orders of knowledge which we might call the practical and the poetic…. each form of knowledge addresses the other and… the frontier between them is there for the crossing.”

The 2014 Summer Retreat

The Middle Way Society’s summer retreat at Anybody’s Barn, Worcestershire, finished yesterday, and I hope that in a few weeks we can put up a page containing various comments from all the Retreatants. However, for the moment I thought I would just post some of my own reflections on it.

The retreat was the first one that has been organised by the society (as the 2013 Middle Way Study Retreat, when the society was founded, was organised by me privately). As such it is a bit of a test-bed, but I expect it to be the first of many (the next will be a weekend retreat in Sussex in November). The overall purpose was to provide a basic understanding of the Middle Way as an approach, combining talk and discussion with practice and allowing the practice to give a wider context to the discussion. So the programme contained two 45 minute meditation sessions (early morning and late afternoon), a couple of hours of talk and discussion (two sessions of about an hour or a bit longer), and a more practical or creative activity in the evening that might take one or two hours. In between there were meals and lots of free time for walks, socialising, naps, reading, or reflection. We had silence up until 10am each morning to provide a focused start to the day, but there was lots of informal discussion at other times.

I’d arrived at this programme by gradually adapting the model I had initially learned in Buddhist retreats and adapting it so that the Middle Way, rather than an adherence to a tradition of what retreats ought to be like, was the working principle. Balance is vital. For retreats to work, people do need to treat them as a special space, and drop everyday distractions such as their mobiles, TV etc, but on the other hand if people are forced into too much of a ‘disciplined’ mould by an excess of one kind of activity, this is liable to produce an unhelpful reaction. I wonder very much about the long term efficacy of extreme meditation retreats, where people do 8 hours of meditation or more, as though meditation was an end in itself and more of it is necessarily better. If one wants to integrate the effects of meditation into one’s life, I think one stands a lot more chance of doing this through integrated activity: though that doesn’t mean that MWS couldn’t run retreats in the future that put a bit more relative emphasis on meditation.

One thing I think I learned from the retreat is that events that one thinks might be very disruptive are not necessarily so, as long as people maintain commitment to the retreat space. Two people had to leave less than halfway through the retreat, and another stayed locally off the premises and had to come and go a lot because of their personal circumstances. On the rather rigid model of a retreat that I had absorbed from my experience of Buddhist retreats, such things would either just not be allowed, or be regarded as disastrous if they happened. But retreats are for people, not people for retreats. Although I didn’t initially set out intending to be quite as flexible as I ended up being about these ‘disruptions’, I ended up feeling that flexibility of this kind was an important part of the way that retreats need to address conditions for real, embodied people. Ordinary people have all sorts of needs and problems that retreats need to accommodate if they are to help them, rather than excluding people because of the fixed idea that a variation of the normal conditions must be seriously disruptive.

The retreat was relatively small (7 people), and only just financially viable (many thanks to Anybody’s Barn for being flexible with their charges), but if we can attract that many people to a successful week-long retreat after only a year of existence, I’m optimistic that we will rapidly gain more credibility and begin to run an increasing number of viable retreats. The people who came along were quite varied in age, outlook, and previous experience. However, a spirit of practising the Middle Way in handling any disagreements soon came to prevail, and by the end of the week (as often happens on retreats) we had all formed bonds of friendship. If you only came on a retreat to make friends, and that was your only motive, it would still be worthwhile. It’s also impressive how easily on retreat people often get down to handling practical activities (like washing up) in a straightforward and harmonious way.

One of my own major contributions to the retreat was the talks, and one of the other points of reflection I will take away from the retreat is to keep improving the way I handled these. My tendency is to be a bit too much motivated by an overall abstract view of what I am communicating, and to go on for slightly too long, because I think about the issues in a very synthetic way, and am also thinking a bit more about the importance of the material itself than of the needs of the embodied people I am addressing. I think I improved on this compared to 2013, as I kept most of the talks down to about 30 minutes – but there were still some that went on a little too much beyond this. I also need to be more thoroughly prepared with examples and engaging stories, as sometimes I still have to be prompted to provide these.

Nevertheless, the audience did seem to get a lot out of the talks. They have all been recorded and, as with the ones on the 2013 retreat, the plan is to put them up on the website in both audio form and augmented audio (i.e. with illustrative summaries and pictures in a video format). They were differently structured from the talks I gave in 2013, and included a lot more reference to cognitive biases, drawing on the work I have been doing on these recently. Compared to last year, they were also oriented less towards addressing Buddhist assumptions and more towards just offering a straightforward and practically-oriented account of each topic (though some of the questions in discussion did still involve the relationship with Buddhism). I made a point of ending each talk with specific points about the application to practice. The headings of the talks were as follows:

- Introducing the Middle Way

- Space and attention

- Embodied meaning

- Archetypes

- Self and ego

- Theories and ‘nature’

- Responsibility

- Value

- Authority

- Groups

- Time

- Practice

Even if you weren’t there, I’d be interested to hear any comments about your responses to the format and style of this retreat – i.e. how it sounds to you. I’m also very interested to hear any suggestions for future retreats that you would like MWS to run. For myself I finish convinced that retreats are the heart and blood of MWS. The internet is all very well for spreading ideas, but it is only by meeting face-to-face and encountering each other in greater depth that we can really start to make a positive impact on changing our lives using the Middle Way.

Picture: scene from the drawing class run on the retreat by Norma Smith (photo taken by her). Although this happens to show 5 men, note that there were also 2 women on the retreat!

Announcing our autumn weekend retreat in Sussex, UK, ‘Meaning and the Middle Way’, 7th-9th Nov 2014. Come and meditate, reflect on embodied meaning, walk on the South Downs, and make friends! Please see this link for more details and to book your place.

‘Meaning and the Middle Way’, 7th-9th Nov 2014. Come and meditate, reflect on embodied meaning, walk on the South Downs, and make friends! Please see this link for more details and to book your place.

Plenty of places still also available on our Summer Retreat in Worcestershire, 16th-23rd August. See this link.

Middle Way Thinkers 6: Jesus

Was Jesus a Middle Way Thinker? Largely not. His beliefs seem to have included many absolutes, and he has also been interpreted since in terms of those absolutes. Yet in this series I also want to encourage incremental thinking. I want to suggest that there are some important ways in which Jesus moved forward from the dogmas of his time, which amount to some specific instances of Middle Way thought. I’d suggest that it is due to these new ways that he addressed the conditions of his time that he gets much of his power. Particularly for those of us from a Christian background (which includes me), I think it’s important to re-examine Jesus in a critical way: one that tries to separate out the dogmas of Christian tradition from those elements that might helpfully speak to our experience.

However, this is a loaded subject, so I’d better start with some clarifications. On the one hand, I’m not interested in supporting any of the dogmas of the Christian tradition about Jesus: either that he was the Son of God, affirmed as some type of supernatural status, or that everything he uttered was ‘true’ and the Word of God. But nor, on the other hand, am I interested in historical revisionism, which seems to be the opposite trap for those interested in re-examining Jesus. I don’t want to make any claims about what Jesus “really” was, or believed, or meant to say. I’m content to work with the Jesus accepted by Christian tradition, and depicted in the four canonical gospels, because that is what ‘Jesus’ effectively means to most people today. I’m looking for insights or symbolic inspiration, rather than historical revelation, in this traditional depiction of Jesus, without getting swallowed up by the various scholarly quagmires of Biblical Studies. The third extreme I’d also want to avoid here, is the mere rejection of Jesus as a source of insights or inspiration. For me, and I suspect many others in the West, Jesus is a powerful archetypal figure, both because of his role in Western art and culture and because of his influence through the Christian churches (very much associated, for me, with childhood experience as a minister’s son).

Let me also briefly note some of the aspects of Jesus that I think are pretty unhelpful. There’s the virgin birth, the idealised childhood, and the sense of divine destiny as the son of God. There are the miracles: at least where these are presented not as acts of compassion but (as particularly in the gospel of John) as signs of divine status. There’s the self-sacrificial aspect: he appears to have basically offered himself up as a sacrifice, aware that he was walking into a trap that would result in his death in Jerusalem, but still doing it. In his trial before Pilate he also seems guilty of false modesty, not offering even a moderate defence to draw people’s attention to his innocence. It seems possible that he believed God would save him from the cross (accounting for ‘My God! Why have you forsaken me?’), because of his profound belief in cosmic justice and an imminent doomsday. Finally, if we follow the role of Jesus in Christian tradition, there’s the interpretation of Jesus’s death as an atonement for human original sin, and the belief in his resurrection as a further sign of divinity and a proof of eternal life for the saved: all these are damaging dogmas by which the moral complexity of our experience is overlaid with crude diagnoses and crude magical solutions.

But, if we can manage to leave all that stuff aside, let’s try to focus on some of the ways that Jesus can be inspiring and insightful – corresponding also to ways that he moves towards the Middle Way. I’d suggest that these fall into two categories: one of these is helpful elements in Jesus’s moral teaching, and the other is helpful archetypal interpretation of the meaning of Jesus as the Son of God.

Much of Jesus’s moral teaching involves a struggle with the Pharisees, who were a sect of Jewish legalists, and the Sadducees, who were conservatives associated with the priestly elite at the Jerusalem temple. Jesus is excoriating about rigid observance of tradition or adherence to the letter of the law, instead urging awareness of motive and the spirit behind the law. For example, when his disciples plucked ears of corn on the Sabbath (against the laws that forbid harvesting on the sabbath, which would be work) and were criticised by the Pharisees, Jesus said “The Sabbath was made for man, not man for the Sabbath” (Mark 2:27). He also emphasised motive in urging people not to be showy about giving alms, “Your good deed must be secret” (Matthew 6:4). From today’s perspective, to merely emphasise motive in ethics is not enough, because our motives vary so much along with our unintegrated desires. However, this emphasis was a major step forward in a context where people were thinking of ethics only as an extension of law, in the form of rigid social rules. On the other hand, Jesus seems to be trying to strike a Middle Way in relation to the Jewish Law, because he does not reject it either: “Do not suppose that I have come to abolish the law and the prophets; I did not come to abolish, but to complete” (Matthew 5:17).

Jesus is also well-known for his teaching of ‘turning the other cheek’ – the apparent pacifism of “Do not resist those who wrong you. If anyone slaps you on the right cheek, turn and offer him the other also” (Matthew 5:39). The key insight here is the necessity of avoiding fruitless conflict. Rather than offering one rigid position in response to another, we need to find ways of reducing (an not acting on) the narrow egoistic identification we may have with ‘winning’ when someone challenges us. However, I also think that the Pacifist interpretation of this verse develops another kind of dogma. If we read it as forbidding violence in all circumstances whatsoever, then we rule out the possibility of violence addressing conditions in some circumstances where it might be the best response.

Jesus also offers what might be regarded as a brief equivalent to the Kalama Sutta in Buddhism, offering the suggestion that we need to consult experience when confronted with a conflict between different dogmatic claims. “Beware of false prophets, who come to you dressed as sheep while underneath they are savage wolves. You will recognise them by their fruit. Can grapes be plucked from briars, or figs from thistles? A good tree always yields sound fruit, and a poor tree bad fruit” (Matthew 7:15-17). Here he seems to be suggesting that verbal claims are not enough, and one of the ways we can judge the justification of conflicting claims is by their integration, evident in people’s behaviour. Again, we could take this to another extreme, by rejecting a person’s view whenever there is a shade of hypocrisy. Hypocrisy does not necessarily make people’s claims untrue, but it is a useful warning sign.

Much more could be said about Jesus’ moral teaching, but I must keep this post brief. More broadly, too, I think Jesus’ symbolic role should also be mentioned. His traditional position in Christianity as ‘Son of God’, both wholly human and wholly divine (according to the Nicene Creed) does not have to be merely rejected as a dogmatic belief, because its meaning can be separated from such beliefs. That meaning is one I encounter very frequently in Renaissance art, where I encounter Jesus as what sometimes seem to be an attempt to represent the Middle Way in human experience. The symbolic richness of Jesus’s status as both divine and human is one way of confronting the profound ambiguity of the relationship between perfect ideals and imperfect experience, the ‘truth on the edge’, or necessity of maintaining a robust conception of truth without claiming to possess it. Jesus is full of contradictions: he is both vulnerable and powerful, wise and foolish, alive and dead, but these contradictions are only damaging as objects of incoherent belief. As symbols, on the other hand, their ambiguity can help us to recognise both the conflicts in our own experience and the ways we can work with those conflicts.

Western art often depicts Jesus in three particular forms: as an infant, in his crucifixion, and in his resurrection. All of these, I think, can be appreciated as offering evocations of that symbolic richness. As an infant he represents the incarnation, that strange ambiguous middle way between divine and human. On the cross he represents the unbearable and unjust suffering of the human condition when understood in relation to divine perfection. When resurrected, he shows the perseverance of hope: that the good can still come through human experience even when we least expect it, when we have come to terms with the conditions of human life. The picture here is an intriguing one by the Mexican artist Orozco. There are many ways of reading it, either as a symbol of resurrection, or as an anti-theistic statement in which mere humanity triumphs.

Western art often depicts Jesus in three particular forms: as an infant, in his crucifixion, and in his resurrection. All of these, I think, can be appreciated as offering evocations of that symbolic richness. As an infant he represents the incarnation, that strange ambiguous middle way between divine and human. On the cross he represents the unbearable and unjust suffering of the human condition when understood in relation to divine perfection. When resurrected, he shows the perseverance of hope: that the good can still come through human experience even when we least expect it, when we have come to terms with the conditions of human life. The picture here is an intriguing one by the Mexican artist Orozco. There are many ways of reading it, either as a symbol of resurrection, or as an anti-theistic statement in which mere humanity triumphs.

I have passed through a number of stages in my response to Jesus. As a child and teenager, I mainly had a negative reaction to the idealised figure I was presented with, who was being foisted on me, but didn’t at all seem to represent the qualities I would have chosen to idealise or to worship. At times, however, I also tried out that idealisation, though I had great difficulty making it my own. I then started to see Jesus primarily as a swindle: an attempt to magically jump across the difficulties of human life. Now, however, I’m quite clear about rejecting a lot of the religious claptrap that surrounds beliefs around Jesus, but at the same time I think I am beginning to develop a relationship with him both as a man and as an icon. As a moral teacher, he can be inspiring, but does not seem to me as hugely significant as he is often cut out to be, and a lot of contextualisation is needed to see how he was moving towards the Middle Way. As an archetypal symbol, though, he means a lot more, and that meaning develops a little almost every time I step into an art gallery.

Postscript (2018)

This article was written in 2014, and since then I have written a whole book, The Christian Middle Way, that is now being published. In that book I give a much more detailed interpretation of Jesus with rather more reference to the gospels. Although this article gives an idea of the direction I was heading in a couple of years before I wrote the book, the view of Jesus that I arrived at subsequently is in many respects more positive than this one.

Robert M. Ellis