A new short publicity video for the society.

All posts by Robert M Ellis

Nostalgia isn’t what it used to be

I have a persistent early childhood memory which is about walking along a track between fields near the Norfolk coast in Eastern England. We used to go for holidays there when I was a child, and there’s a strong set of associations between contentedly walking in early evening sun, a dry, beaten track carpeted with pineapple weed and common plantain, overgrown late summer vegetation beside the track, and wheat fields beyond. Several times recently I have realised that when walking along in a contented frame of mind, this memory is often at least partially evoked. Perhaps it is the late summer vegetation that can give me a partial taste of this memory when walking along a track, even where the landscape is otherwise quite different.

Is this nostalgia? Well, that all depends on how you define the term. I would rather distinguish nostalgia from this kind of experience of the past giving meaning to the present. Nostalgia involves hanging on to the past in some way, absolutising it in a way that distorts the present: but this experience seems rather to augment the present and make my experience of it fuller. I appreciate the flavour of the present landscape more because it is also, simultaneously, this past landscape. I think, perhaps, we often do this – probably more often than we realise. We integrate our experience through time by to some extent having one experience in the present in the terms of one in the past. That way the meaning that we attributed to the past experience is added to the present experience, not taken away from it.

Writers make a great deal of use of this phenomenon. There is Marcel Proust’s famous example of the taste of madeleine cake, that evokes a whole set of previous experiences. There are many novels in which writers have incorporated their own youthful experiences into a fictionalised narrative that carries more power because of it, such as D.H. Lawrence’s ‘Sons and Lovers’. In some of these, though, perhaps we can be doubtful about whether we are dealing with the meaning of the past augmenting the present, or nostalgia of a narrower kind.

Nostalgia of a narrower kind I would take to involve forming beliefs about the past experience that then distort one’s judgements about the present. The other day, accessing the Norfolk experience when walking, I began to see how it could turn into nostalgia. Supposing, in pursuit of this lovely memory, I tried to re-experience it. I might drive for several hours back to Norfolk and go in search of the exact spot where my childhood memory took place. The chances are, however, that I would be disappointed. Even if the landscape and the weather happened to be as I remembered them, I would have changed in a way that would make that fleeting mood that has somehow got engraved on my memory elusive. I would probably feel that I was having a boring adult experience of walking along that track, not an enchanted childhood one. Trying to recapture that experience, rather than integrate it, would be an absolutising move, taking an abstract idea of that experience and exalting it in a way that does no justice to its context in experience, then or now.

One kind of extreme absolutising response would be to idealise the experience nostalgically, and the other would be to dismiss it and assume that the experience is not relevant to me now. But the Middle Way seems to involve the possibility of a full acknowledgement of the power of that experience, together with an acceptance that now, forty years later, my experience is different. This is not just a version of the commonplace observation that we cannot recapture the past, for we can indeed recapture the past, in the present. Somehow the past can carry on enriching the present.

Perhaps this is the gift of age? I’m sure those older than I am can say more about whether this can happen further the older one gets. Is the savour of past experiences potentially integrated more with present ones, the more past experience one has? The gift of youth might be single-pointed, full-blooded experiences that age cannot recapture, but the gift of age might be multifaceted, rich, complex experiences of the meaning of the present integrated with the past.

New review – ‘Emptiness and joyful freedom’

I’ve now posted a new review of ‘Emptiness and Joyful Freedom’, a book by Greg Goode and Tomas Sander that tries to take the emptiness teachings of Buddhism beyond the context of Buddhist tradition. In the process I’ve included some discussion of why I don’t normally use ’emptiness’ terminology, and don’t find it particularly helpful in discussing the Middle Way. See this page to read the review. Robert

I’ve now posted a new review of ‘Emptiness and Joyful Freedom’, a book by Greg Goode and Tomas Sander that tries to take the emptiness teachings of Buddhism beyond the context of Buddhist tradition. In the process I’ve included some discussion of why I don’t normally use ’emptiness’ terminology, and don’t find it particularly helpful in discussing the Middle Way. See this page to read the review. Robert

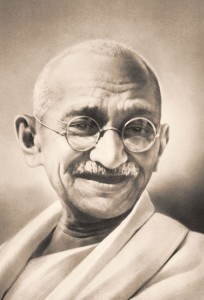

Middle Way Thinkers 7: M.K. Gandhi

M.K. Gandhi was a Middle Way thinker in very striking practical respects. I count him as such not because of his obviously metaphysical beliefs about God, Truth, and the ultimate unity of religions, nor because of his commitment to Pacifism, but because of his courage and innovation when it came to dealing practically with conflict and providing us with tools for non-violent political change. Gandhi’s key insight was that the whole concept of any enemy is a projection of narrowed, dogmatic representations of the world. Our desires may conflict with others’ desires, but that conflict needs to be resolved by integration, not by a victory that eliminates the ‘enemy’. The conflict we may have with ‘enemies’ reflects a conflict within ourselves and within that person, which is not resolved by ‘winning’ the conflict.

Instead, in a case of conflict like that between exploited Indians and the ruling British of imperial India, the resolution of the conflict comes from making opponents recognise the conditions they are ignoring in their unnecessarily narrowed view of the world. They can be led into this by being led to see the humanity of those they are oppressing, and the similarity, rather than just the difference, between their concerns and those of the group or individuals they have previously seen so rigidly. If they cannot be positively persuaded, they need to be shocked into an act of imagination.

The recent death of Richard Attenborough prompted me to re-view the great biopic of Gandhi that he directed, and I highly recommend that film to get an impression of the man (selective though it inevitably is). The following scene from the film depicts the disciplined practice of non-violent protest that Gandhi inspired and organised, though Gandhi himself does not appear in this clip (he had just been imprisoned). The march on the salt works was inspired by the injustice of a British state monopoly on the making of salt, so in effect the salt works symbolised British imperial rule.

At one time I used to think of this scene as masochistic, but now I no longer think of it in this way. There seems to be no sign that the protesters lacked confidence or had any sort of craving to be hurt. Masochism reflects a conflict and repression within, but I see no sign of that in these men (though of course it is a reconstruction, and who knows what motivated the original men). Rather their willingness to incur injury to themselves for their cause could be seen as the result of their commitment to integration: not so much a self-sacrifice as a recognition that voluntary physical injury to oneself is in the end less important than the integration they were trying to bring about.

This, at least, is how I now read the practical insights that Gandhi reached, in which I see a powerful example of the Middle Way in action. In practice, in his political campaigning at its best, Gandhi seems to have neither stuck dogmatically to an interpretation of his beliefs that would cause immediate conflict, nor gone to the self-sacrificial opposite extreme of giving up the cause that he identified with and understood the justice of. It is in his private life, revealed particularly in his Autobiography ‘My experiments with truth’, that I find a much more dogmatic Gandhi: one whose absolute beliefs led him to repress his own passions and to have an inconsistent response to his sexuality.

Gandhi called his technique Satyagraha, ‘truth grasp’. At times he seems to stubbornly assert that he has a grasp of truth of a metaphysical kind, but at other times I can read Gandhi’s relationship with ‘truth’ as something he found profoundly meaningful and interpreted with humility, a truth on the edge. Though he was an imperfect human being like the rest of us, he is also a thinker who forged his understanding of the Middle Way in the heat of action.

Just another dogma?

A new page is now published to engage with a common reason for dismissing the Middle Way – the assumption that it’s just another dogma amongst all the others. See Isn’t the Middle Way just another dogma?