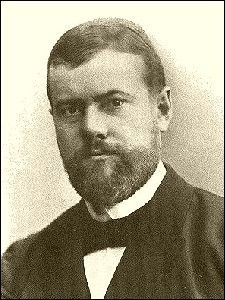

Recently reading a review of a new book about Max Weber (1864-1920), I was reminded of how much of an effect his thinking in ‘The Protestant Ethics and the Spirit of Capitalism’ had on me when I was first writing my Ph.D. thesis (which was when I first started to develop Middle Way Philosophy about 15 years ago). He’s often thought of as a pioneering sociologist, but you could also see him as a kind of historian and/or philosopher, and his interests took in religion, politics, and economics among other things. In effect, he was one of those great thinkers who refuses to be pigeonholed. He famously said “I am not a donkey and I do not have a field”. He was also relatively uninterested in most of the trappings of academia, and managed to maintain a relatively objective political position through the First World War in Germany without being dragged into what he called the ‘politics of vanity’.

In ‘The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism’ he points out the important historical link between Catholic monasticism, Protestant worldly asceticism, and Capitalism. The story is roughly this: the medieval monks developed an ascetic mentality of self-denial in a higher cause, together with an individual relationship with God in which they felt accountable to him for their deeds. The monks were also used treating the monastery’s property as corporate. In the Protestant countries at the time of the Reformation, this asceticism was taken over into wider society rather than being confined to the monasteries. The Protestant began to have an individual relationship to God that went together with the literacy and accounting that had formerly been a monastic preserve. Capitalism then began to develop in Protestant societies because the basic requisites for it were there: an ascetic culture of self-denial allowing investment for future profit, a culture of book-keeping (whether moral or financial), the specialised organisation of free labour, and the separation of corporate property. Though of course, trade and industry had existed before this, it is these practices that enabled it to really take off in Europe and create the capitalist world we know today.

What makes this particularly interesting from the standpoint of the Middle Way is the way in which it shows the increasing dominance of a left-hemisphere formed, regularised, bureaucratised view of the world in Western culture. Far from being separated or antithetical, the worlds of ‘religion’ and ‘economics’ also turn out to be deeply inter-related, both shaped in parallel ways by this narrowly focused view of the world. To begin to loosen the grip of that narrow perspective and integrate it into a wider one, it helps to understand some of the conditions that formed it for us. These conditions have now spread into nearly every other area of life, where they tend to take the form of what is often called ‘managerialism’: if you can represent things and keep close control over them, this view goes, they will fulfil your desires more fully in the future. Max Weber seemed to understand clearly, more than a hundred years ago, how much of a delusion resided in this approach to life.

The last few pages of ‘The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism’ offer a remarkably prescient account of the ‘iron cage’ created by this narrowed, bureaucratised view, and the ironic way this has emerged from religious other-worldliness. Though written in 1905, it begins to foreshadow modern concerns about sustainability. I will finish with a quotation from there:

The Puritan wanted to work in a calling: we are forced to do so. For when asceticism was carried out of monastic cells into everyday life, and began to dominate worldly morality, it did its part in building the tremendous cosmos of the modern economic order. This order is now bound to the technical and economic conditions of machine production which today determine the lives of all the individuals who are born into this mechanism, not only those directly concerned with economic production, with irresistible force. Perhaps it will so determine them until the last ton of fossilised coal is burnt. In Baxter’s view the care for external goods should only lie on the shoulders of the “saint like a light cloak, which can be thrown aside at any moment”. But fate decreed that the cloak should become an iron cage.

(A more detailed discussion of Max Weber’s arguments and their critics can be found in my thesis here.)