Another video about groups! The timing of it coming out just after the previous one is just a coincidence. However, the approach in this one is a bit different, it being made as part of the ‘Mistakes we make in thinking’ series. The intended audience is wider, so it’s not framed in terms of Middle Way Philosophy but in terms of avoiding cognitive errors, drawing on psychology and critical thinking.

All posts by Robert M Ellis

Groups

This enhanced audio is the latest release of edited material from the 2014 Summer Retreat talks and discussions. We are social animals who can’t help relating in groups, by why are groups so often oppressive and dogmatic? How can we strike a Middle Way in relation to groups?

Breaking down the Walls of Fortress Europe

I’ve been thinking for a while that I should write something here about the refugee crisis that has been stirring up passions in the media and social media in Britain (and I suspect in Europe and the US too) in the last few weeks. I have been struck for some time by the dogmatic features of a lot of discussion about immigration (though not all), so what I really want to do here is just point out some of the dogmas that I think need to be avoided if we are trying to apply the Middle Way to the issue. Beyond a certain point, in such a complex issue, the Middle Way doesn’t give us specific answers to the dilemmas involved. Questions like exactly how many refugees to admit, how exactly they can be accommodated, or how to avoid encouraging criminal gangs from people-trafficking operations are all more detailed questions of policy on which I’m going to try to avoid being too prescriptive. Instead, I want to reflect on the effect of frontiers on our thinking

National frontiers are political absolutisations of differences in geography, history, language, culture, religion, ideology etc that would otherwise be incremental. If I travel overland from England to Mauritania, say, I will pass through only 3 other countries (France, Spain, and Morocco), and as I go the climate and culture will gradually but imperceptibly change. By the time I reach Mauritania I will be in a poverty-stricken, Islamic, desert land where slavery is still common: a starkly different place from England. However, since national boundaries in the Sahara are extremely difficult to police, and under the Schengen agreement France and Spain share an open zone, that whole difference has become concentrated at the Straits of Gibraltar (and to a lesser extent at Calais). There migrants and refugees try to scale the fences of the Spanish enclaves of Ceuta and Mellila, just as they try to cross the sea between Libya and Italy or between Turkey and Greece. All European fear of the Other has become concentrated on those borders, with ‘home’ extended to one side of them and the Shadow lurking on the other side. The British tabloid newspapers have exacerbated this kind of reaction by using consistently negative or dehumanising language about the ‘swarms’ (a word used even by David Cameron) on the other side of it.

National frontiers are political absolutisations of differences in geography, history, language, culture, religion, ideology etc that would otherwise be incremental. If I travel overland from England to Mauritania, say, I will pass through only 3 other countries (France, Spain, and Morocco), and as I go the climate and culture will gradually but imperceptibly change. By the time I reach Mauritania I will be in a poverty-stricken, Islamic, desert land where slavery is still common: a starkly different place from England. However, since national boundaries in the Sahara are extremely difficult to police, and under the Schengen agreement France and Spain share an open zone, that whole difference has become concentrated at the Straits of Gibraltar (and to a lesser extent at Calais). There migrants and refugees try to scale the fences of the Spanish enclaves of Ceuta and Mellila, just as they try to cross the sea between Libya and Italy or between Turkey and Greece. All European fear of the Other has become concentrated on those borders, with ‘home’ extended to one side of them and the Shadow lurking on the other side. The British tabloid newspapers have exacerbated this kind of reaction by using consistently negative or dehumanising language about the ‘swarms’ (a word used even by David Cameron) on the other side of it.

Whatever judgements we make need to avoid that absolutisation. Of course, when people of very different cultures are brought together (particularly when they have to share resources), difficulties of communication, adaptation and adjustment will follow. We can’t ignore that condition, but it is an incremental condition, a matter of degree. The ‘swarms’ on the other side of the wall not only share our basic humanity, but are like Europeans in lots of other ways too. Probably to list such ways would be patronising: anyone who has heard refugees interviewed on the media will have an impression of how much refugees are often not very different from us. Indeed, many people who have been refugees in the past are now settled citizens of Britain, the US, and other such countries.

It’s striking how the British tabloid Daily Mail, particularly, moved suddenly from dehumanising refugees to sympathising with their plight, after the shift in public mood that seems to have been triggered by pictures of drowned refugee children. But to blame them for that inconsistency (rather than for their previous negativity) is fallacious: we are all moved by such pictures, for we are embodied humans, not rational automata, and if those emotions help us to address conditions we were not previously addressing, that is helpful.

Frontiers also give us a sense of protective and egoistic ownership over ‘our’ land on this side of them, and this protectiveness can extend to worries about employment, the shortage of housing, and strain on welfare systems. But if we incrementalise such concerns, rather than absolutising them, we may be able to see them in better proportion: perhaps minor inconveniences or drops in service provision for us, and a major help to refugees. Perhaps if refugees did enter Britain in the kind of numbers they have been entering Turkey (where there are 1.9 million, according to UNHCR), we would see a noticeable increase in the strain on housing and welfare (employment is perhaps a different matter, as enterprising people can create their own jobs). But why should Turkey take that strain rather than Britain? How much difference would it really make to everyday life in Britain? Even if some British people would suffer to some extent in some ways, how would that suffering compare to the suffering of the refugees?

Yes, there are all sorts of practical difficulties that stand in the way of breaking down the walls of fortress Europe. I was in a local Green Party meeting the other day that brought some of those difficulties home to me: for example, currently a town in the UK that wants to host refugees will only be funded by central government for the first year to help the local authority meet their needs. Many councils are rejecting the prospect, because they fear that their overstretched budgets will be stretched still further by responsibilities for traumatised people that go on beyond that year. One can hardly blame local council officials, who have to make it all work, from being concerned about such points.

But we also need to keep in mind the big picture that such objectors neglect: that Europe cannot forever maintain a fortress policy. Exactly the same point applies to other developed countries, such as the US and Australia. How many refugees do there have to be, and how desperate do they have to be, before such policy becomes impossible to maintain? No border is absolute, not just in philosophical terms, but in terms of practical maintenance. If climate change produces a great many more refugees, as is often predicted, how will we deal with this? You cannot shut off a large portion of the world’s conditions behind a wall and pretend it is not your business – or if you do, you are engaging in repression, and that repression has a habit of springing back in the future with unexpected and often violent effects. Other social, economic and technological forces are also making the world more integrated, not less. It has been remarked that one of the drivers of the current wave of migration is the internet, where migrants can easily find out about their dreamed-of destinations.

How we precisely address these conditions is another matter. An open-door policy might actually produce a lot less conflict and suffering in the long-term. Of course we shouldn’t neglect the possibility of social conflict that might be created by such a policy. The details of where the right balance lies can only be worked out by those responsible, with all the practical information. But for those of us on the sidelines the general best policy seems clear: we need to work on the basis of the big picture, and that also means opening our hearts – not indulging our projected archetypal fears about the shadowy people on the other side of the border.

Picture: Syrian refugees in Lebanon (public domain)

Appeals to Authority

A new video, the second of a series that attempts to clearly explain an area of cognitive error and how we can work to avoid it. A resource for objectivity training!

Objectivity training

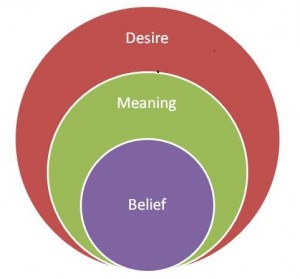

In my account of practice in Middle Way Philosophy, I have identified three (interlinked) kinds of practice area, which I call integration of desire, integration of meaning, and integration of belief. To integrate desire the central practices will be meditation, or other practices involving body awareness. To integrate meaning the central practices are likely to be the arts. To integrate belief, so far I have often focused on critical thinking as a central practice. To distinguish these types of integration and link them together in this way seems to involve a distinctive emphasis: but still, the practices of meditation and the arts themselves are widely recognised as beneficial in all sorts of ways. I have been thinking more recently of the third area as one on which I need to focus, because, although it has all kinds of links to academic practice, it is rarely either seen as integrative or linked effectively to the other types of integration. Instead, the habit of many people seems to be to fence these areas off as ‘intellectual’ concerns of interest only to a minority of boffins. The whole area of working with awareness of our beliefs and judgements, perhaps, needs a re-presentation.

I have been thinking more recently of the third area as one on which I need to focus, because, although it has all kinds of links to academic practice, it is rarely either seen as integrative or linked effectively to the other types of integration. Instead, the habit of many people seems to be to fence these areas off as ‘intellectual’ concerns of interest only to a minority of boffins. The whole area of working with awareness of our beliefs and judgements, perhaps, needs a re-presentation.

Lately I have hit on a label for the whole enterprise that might be helpful in doing this. ‘Critical thinking’ has not really been doing that job well for several reasons. People tend to associate being ‘critical’ with narrowness and negativity, which obscures the ways in which it can help one cultivate the reverse. Critical Thinking courses are also often narrowly focused on the structure of reasoning and mistakes we can make in reasoning: which are good things to study, but they miss out the whole important psychological dimension of the integration of belief. What should we call the whole study and practice of mistakes we make in thinking (not just in ‘reasoning’, but also in our emotional responses and the attention we bring to our judgements)? It has struck me recently that ‘objectivity training’ might be a better term to use for this. The term ‘objectivity’, of course, is also still used by too many philosophers and scientists to mean a God’s eye view or absolute perspective of a kind we can’t have as embodied beings, but surely if it is paired with ‘training’ it’s going to be reasonably obvious that we’re talking about helping people to make incremental progress in avoiding delusion and facing up to conditions?

So how can you train someone to be more objective? By helping them to be aware of the kinds of cognitive errors we are all inclined to make, and helping them to train attention on such errors. That’s never going to provide any guarantee that your judgement is right, but it can help us avoid certain easily identifiable sources of wrongness that we can all easily fall into through lack of attention. If you can avoid the errors, you will then have a more trained judgement, and that will give you a much better probability of making adequate responses to whatever the ‘reality’ we assume to be out there may throw at us.

There’s lots of evidence available of what those errors are, and why human beings generally tend to share them. That evidence comes from both philosophy and psychology, and one of the distinctive things I want to do is to fit the contributions of both these studies together as seamlessly as possible, with Middle way Philosophy as the stitching thread. The kinds of errors we make can be encountered in three categories:

- Cognitive biases as identified in psychology (or, to be more precise, the elements of cognitive biases that we can do something about, and that are not just unavoidable aspects of the human condition): for example, actor-observer bias or anchoring

- Fallacies, particularly informal fallacies, as identified in philosophical tradition: for example, ad hominem or ad hoc argument

- Metaphysical beliefs in dualistic pairs, as recognised and avoided in the Middle Way : for example, realism and idealism, or theism and atheism

In the end I think there is no ultimate distinction between these categories, and they often mark the same kinds of errors that have just been investigated and understood from different standpoints. What I think they have in common is absolutisation: the tendency for the representation of our left brain hemisphere to be accompanied by a belief that it has the whole picture and that no other perspectives are worth considering. We can absolutise a positive claim or a negative claim, but when we do so we repress the alternatives.

For the full argument as to how absolutisation links all these kinds of errors, you’ll have to see my book Middle Way Philosophy 4: The Integration of Belief, which makes the case in detail. However, the main reason for focusing on absolutisation is the practical value of doing so. Objectivity training is a training in bringing greater awareness to spot those absolutisations when they happen, realise they are not the whole story, and open our minds to the alternatives before we make mistakes, entrench ourselves in unnecessary conflict, and fail to solve the problems we encounter due to an inadequate engagement with their conditions.

What does objectivity training actually involve? Well, it’s something I want to focus on developing further and testing out in the next few months or years. Here are the general lines of what I envisage though:

- Becoming familiar with cognitive biases, fallacies and metaphysical beliefs – not just as isolated abstractions, but in relation to each other

- Developing understanding of why these errors are a problem for us in practice

- Becoming familiar with examples of these errors

- Identifying these cognitive errors in actual individual experience: this might involve reflection on past experience, critical reading and listening, observation of others with feedback, anticipating contexts where errors will take place, development of attention around judgement through trigger points and general use of mindfulness practice.

This is not just ‘logic’: rather it focuses on the assumptions we make. Though some of the mistakes may be identifiable as errors of reasoning, most will not, and part of the problem may well be that our narrow position seems entirely ‘rational’ to us. Nor is it just therapy, though it may have some elements in common with cognitive behavioural therapy. It needs to be an autonomous aspect of individual practice, rather like meditation and mindfulness (with which it needs to have a near-symbiotic relationship).

I think it’s really important that more people in our society learn these kinds of skills. They can be applied to our judgements everywhere: in politics, in business, in personal relationships, in spending judgements as consumers, in scientific judgement, in our attitudes to the environment, in our judgement about the arts, in leadership, in education and so on. In some of these areas, such as environmental judgement, we very urgently need to improve people’s judgement skills.

I think there is huge potential for this type of training, which is why I want to focus on developing it. But the other forms of integrative practice are also very important, which is why I hope that other people will emerge in the society who are able to take more of an effective lead in developing and teaching distinctive Middle Way approaches to meditation and the arts.