I’ve produced this new video to help publicise the Objectivity Training Course which I’m running May 31st-Jun 3rd in Malvern, UK. That’s only 6 weeks away at the time of posting this, so if you’re planning to come, please book without delay! This 4 day intensive course should allow you to understand the inter-relationship between a range of different kinds of assumptions that interfere with our judgement, and develop some practical strategies for avoiding them. The web address given at the end of the video, for more information about the course, is also linked here.

All posts by Robert M Ellis

The 12 Steps of Addiction Recovery: Are they in the spirit of the Middle Way?

A dialogue between Robert M. Ellis and Peter Sheath

(Robert’s contributions are in black throughout, and Peter’s in red)

Robert: The 12 Steps are a successful method of addiction recovery that has been used by Alcoholics Anonymous and its sister organisations since the 1930’s. After my recent discussions with Marc Lewis about addiction, and also inspired by this interview with a pair of philosophers who have analysed the 12 steps, I have been interested in looking more closely at the 12 steps to see how far their success can be attributed to a compatibility with the Middle Way. My thesis is that at least a part of their practical success in facilitating recovery must be due to the ways in which they help addicts avoid explicit or implicit absolutisations, whether positive or negative. Whether a particular text operates as an absolutisation or helps people to avoid it, however, depends entirely on its practical interpretation in context. This is a particularly interesting point in relation to the 12 steps, which use a lot of religious language, though it seems that this language has been interpreted in a very practical way.

Lacking any practical knowledge of the interpretative context of AA and associated organisations myself, I am pleased to be able to collaborate with Peter Sheath by getting him to bring his practical experience to bear in commenting on the accuracy (or otherwise) of my suggested interpretations of the 12 steps. Peter has long experience of working with addiction recovery, and was recently interviewed by Barry in the Middle Way Society podcast.

The way I will proceed, then, is to offer commentary on each of the 12 steps and how they might be interpreted in relation to the Middle Way. Peter can then add his response to each one. I will be quoting the original wording of the 12 steps, though I understand that variations have been introduced by different groups.

Peter: I get your point here. It’s akin to most quasi-religious/spiritual teachings in that, for some, the text becomes ten commandmentish, fundamental and dogmatic. I believe the 12 step programme was never intended to become that, but considering the background, the Oxford group, the temperance movement it’s no wonder it did. As you point out, the language is very religious and can lead to it being interpreted in that way. I guess that’s why sponsorship and finding a meeting that fits you is so important this is how the often “absolutist” text gains context and nuance and develops psychological flexibility.For me context is everything and my interpretation and subsequent application of the 12 step programme has changed quite dramatically over the years.

There are a few things we probably need to discuss before we get to offering our interpretations of the steps;

The 12 steps are part of a much wider recovery landscape based on fellowship, honesty, open mindedness, willingness, sponsorship, service, anonymity, change and values based living. The steps are mainly for the individual but there are also 12 traditions, for the group. As well as working through the steps, with someone who has integrated them into their life (sponsor), it is recommended that people offer service (making tea, greeting, etc.), attend as many meetings as possible, remain anonymous as far as possible, learn to meditate and/or pray, learn to listen, and practice humility and honesty.

Fellowship is very important because, for most people, their substance use and/or behaviours will have led to social isolation, loneliness, and a feeling that there is only me suffering like this. One of the constructs of this kind of fellowship is the honesty with which group members share their stories. At my first meeting I heard people talking about all the personal experiences I had kept hidden for all of my life. For the first time I heard people talking openly about thoughts, fantasies and feelings that had been going on in my mind, since childhood, and for which I felt deeply ashamed of. I also heard people talking about things they had done which I had done that I was absolutely convinced no one else had. I can’t begin to tell you just how relieved it felt to know, in that instant, that I was not alone.

This is why honesty is also very important because it is probably the thing that attracts people back to their next meeting. Anonymity is also very important, it’s important on one level to ensure that people attending the group have their identity protected and feel that they can say things within the confidence of the group with the reasonable reassurance that it stays there. On another level, and what I feel is probably more important, is that anonymity is often the antidote to egotism and hubris. It helps to take the self, or more importantly, the false selfish self of addiction, out of the picture and becomes the vehicle through which we learn things like humility, being of service and altruism.

Personally I think the beauty of 12 step programmes lies in their flexibility and adaptability. As a sponsor I always ask people to read widely before committing to a particular way of working through them. Some will prefer a quite fundamental/religious and very rigorous way of doing it, others will opt for a kind of Gestalt more serendipitous process using the steps and the programme as a kind of social scaffolding around which they construct their recovery. Many in 12 step land will disagree with me here and would probably say something like, “strict adherence to the programme is not optional.” I like to help people to find what is going to work for them, I also like to work at their pace in their time and meet them, psychologically, where they are.

I’ve found that the programme works for some at a very classical conditioning, almost rote learning, level. The whole thing becomes more a behavioural/rational/academic/objective exercise rather than a subjective/emotive/spiritual/often irrational psychic journey. People often learn to quote verbatim whole chapters and learn to recite them at every opportunity. Don’t get me wrong this does actually work for many people and lots have achieved decades of sobriety in this way. What I will endeavour to do is to illustrate this duality as I elaborate on what you have written for each step.

All of the steps begin with “we”, this is very important as it begins to shift a “me” or “I” perspective, associated with the culture of addiction, to a “we “perspective more in line with a culture of recovery. Subtle messages like this can be found throughout the programme.

- We admitted we were powerless over alcohol—that our lives had become unmanageable.

This on the face of it sounds like a deterministic starting point that denies our ability to change our relationship with addictions, but it could hardly function or have been interpreted in that way in practice. After all, it stands at the start of a process in which addicts are gaining control of their lives rather than losing control. Jerome A. Miller, in the interview linked above, suggests that I would say that “the first step is all about realizing that efforts to be in control really are self-defeating”, and I think that should probably be clarified still further – that efforts to be in complete control are self defeating.

Maybe there’s a bit more to step one, especially in the context of “control” as you talk about it here. As I see it, control, or maybe the illusion of control or even the ego’s desperate attempts to maintain control, are fundamental drivers in addiction. There is a cliché, that I picked up many years ago and use to this day, that I believe illustrates this really well, It goes, “when I take control, I lose control”, and I believe that this is the point of self-awareness that step 1 is trying to achieve. I’ve heard all sorts of metaphors like, “the disease”, “the sleeping rat”, “my addict”, that attempt to help this process of awareness raising. The ego, being as it is, wrapped up in mid brain survival functioning, this awareness raising and subsequent ego surrender is no mean feat. This part of you has served you well for many, many years and, for some including myself, has probably prevented them from killing themselves. Although there will be some kind of recognition that what is happening is problematic on one level, on another level it will be seen as far from problematic and may even be the only solution they have ever found. If we are to “change our relationship with addictions”, through a psychospiritual process, which I believe the 12 steps are, then there needs to be some sort of shift away from ego reliance to something other.

The extremes of freewill and determinism both seem to be absolutising traps for those trying to address any kind of difficult condition in their lives. We have to acknowledge that we do not have complete control over the conditions we are working with, whether these are within or beyond ourselves. We cannot simply change all these conditions by an ‘act of will’ and those who believe that we can are failing to recognise the power of entrenched synaptic circuits. On the other hand, neither are we powerless. If we were really powerless we would just be giving way to a problem like addiction rather than trying to address it in a helpful context like AA. The solutions have to involve long-term purposes and reframing of our beliefs about the addiction. So this first step seems to involve just the recognition of these conditions, and that we cannot just overcome a problem as deeply-rooted as addiction by an ‘act of will’. “Our lives had become unmanageable” may also mean a recognition of how negative the effects of addiction had become, and that those effects must be accepted rather than denied.

So what at first seems deterministic here, must have in practice been pointing people towards the ambiguous space between freewill and deterministic explanation: a space in which we can experience progress, but cannot ultimately prove its basis.

For some step one will be very behavioural and fall in line with the learning process of unconscious incompetence, conscious incompetence, conscious competence and unconscious competence. It also follows Procheska and DeClementi’s cycle of change precontemplation, contemplation, action, maintenance. In both models for learning and/or change to take place there must be some acknowledgement that the way I’m currently doing things is no longer working so I need to stop and render myself teachable.

On a deeper level, and probably more in line with a Marc Lewis neurological perspective, words like powerlessness and unmanageability begin to become relevant. Maybe there is a realisation that the addiction is much more serious and all-consuming than what was first thought. Maybe this realisation brings with it a recognition that life has become more about survival and the ego (willpower) has become so depleted that it can no longer be called upon to support quitting. Maybe this recognition, in turn, brings with it a real and awful sense of the extent of the unmanageability of your life and the desperation it entails.

On a more spiritual level perhaps there has been a collapse in the psychospiritual culture associated with the addiction. Maybe it’s got to the end of the road, all options have been exhausted and it’s entered a dark night of the soul. The only option left is to surrender everything to it, in a very profound way, making room for a power greater than you to become active in your life. It’s very difficult to explain this within an objective, rational, scientific context. The experience is wholly subjective, probably irrational to the observer and probably wouldn’t stand up to scientific scrutiny. Nevertheless it is a very real, very human experience that is probably best described as a spiritual awakening.

- Came to believe that a Power greater than ourselves could restore us to sanity.

Step one can be a very scary, painful and guilt provoking experience. It can leave people feeling worthless, emotionally raw, shameful, angry and guilty. In the narcotics anonymous step working guide there are over 90 questions specifically designed to get you to realise the impact your addiction has had/is having on you, your family and the world around you. Almost immediately after completion of step one you will need to begin your healing process with the belief that only a power greater than yourself can restore you to sanity.

Again, for some, this power may be a sponsor, the group, the 12 step programme. It’s kind of saying, “I definitely can’t but I believe, at this stage, we can.” Step one can make the whole experience of addiction appear quite insane and irrational, hearing others with similar experiences, reading about it in the literature and/or discovering a possible connection with the divine (a power greater than ourselves) helps to begin a healing process out of the pain of the surrender.

- Made a decision to turn our will and our lives over to the care of God as we understood Him.

On the face of it, these two steps (2&3) seem like an appeal to God to take over responsibility for the addict’s life. But again, it may in practice have been interpreted in terms of the need to relax our belief that we can fix long-term problems through acts of will. The stress on “God as we understood him” seems to indicate a God of individual archetypal experience rather than a transcendent God who merely gives us instructions or merely fixes everything for us.

A God of archetypal experience would mean getting in touch with a wider experience, wider goals, and thus a more integrated experience. A Jungian account of God as an archetype here sees him as a projection of the integrated or individuated self – that is, of a self who has overcome the conflicts created by addiction and become more whole. By turning themselves over to God, then, addicts could be effectively committing themselves to acting in harmony with their more integrated selves.

Addicts trying to practise this step are often portrayed as praying, and such prayer could have the crucial function of interrupting a habitual narrow focus and allowing wider awareness to re-emerge. This could be linked with body awareness, mindfulness, and the relaxation of the absolutised goals of the over-dominant left hemisphere of the brain: allowing in more of the open, silent experience associated with the right hemisphere. It’s only by relaxing the obsessive way we may represent our goals in an addicted state that we can begin to connect to more profound and longer-term goals that may have been temporarily neglected.

To move towards the new reality, new identity, and new responsibility, associated with the culture of recovery, a profound and sustainable shift needs to occur in almost everything. This “handing over of our lives and our will to the care of god, as we understood him,” enables us to begin to develop our belief from step two and make it into something we can trust, inherently know as a force for good and form a relationship with. I have found that, for some including myself, this was a very tall order. I have had major trust issues for much of my life and religion, which I thought initially was on offer here, had little or no appeal to me. Furthermore I had really struggled with getting intimate with anything which seemed to be a pre-requisite of this step.

The god of my understanding I eventually went with was and, in many ways, still is is a combination of nature and love. Both seem to underpin everything, connecting the universe and the people in it. They involve constants, laws, synchronicity and vibrations which don’t tend to happen in addiction so if I was going to find my place within this, then I needed to begin to hand my will and my life over to it.

I have also discovered since that addiction exists mainly as part of mid brain survival mechanisms. Cortex activity like thinking things through, predicting the future, awareness of consequences and conscience become more and more limited as the instant grat of the mid brain becomes the only show in town. It’s going to be really difficult to think yourself out of this but having a belief in a higher power and a faith that it can put you right may offer a solution.

- Made a searching and fearless moral inventory of ourselves.

The ‘searching and fearless moral inventory’ does strongly suggest the Protestant tradition of moral self-accounting. Here the left hemisphere must more strongly come into play by developing clear ideas about oneself and one’s situation. This must primarily be about the addict recognising that they are addicted, and accepting how hard it will be to end that addiction.

The value of this step seems to be one of clarification. To engage in any long-term course of action you do need to have a clear model of what you are trying to do, but it also needs to be an adequate model that incorporates as much information as possible. If the scale of difficulty is not clear, it would be easy for the addict to deceive themselves that they were making progress when they were actually rationalising the path back into a relapse.

I really like your points here around left hemisphere, recognition of the addiction and the acceptance of the difficulties of terminating the relationship with it. It is indeed about clarification and, the always present, propensity for the return to addictive thinking and self-deception. All of this can find itself framed within a very rational context because of it’s, often seemingly inseparable links to survival instincts like procreation, gregariousness, safety and stress avoidance. It is very difficult to separate instinctual/survival drives/drivers from those associated with addiction. Step 4 goes some way towards helping with this process. The best illustration I have come across in this area is a book called the steps we took by Joe McQ.

When almost everything, for many years, has been about survival, using, medicating and social isolation it’s very difficult to even contemplate a different perspective. Lots and lots of coping and mental defence mechanisms will have been created, embedded and served you well probably since childhood. Many of these will be fully integrated into the false self/ego state that rules the roost in addiction often burying the real self and superego under a veneer of things like arrogance, manipulation, deceit, lies and justifications. The real self has become somewhat lost and in a constant state of submission to the power and control of the ego. By shining a light on this false self, looking at specific examples of it in action and experiencing the consequences in the here and now you can begin to make some sort of sense of it. By listening to others sharing their step 4 and reading step 4 material you begin to realise that it’s not just you.

Resentments play a big part in step 4. Often these will be quite longstanding, totally unproductive and often have either lost their validity or may even have been more from a position of fantasy in the first place. Sometimes these resentments can be quite delusional and involve intricate but very tenuous connections that have become quite paranoid.

The process also becomes quite cathartic as it moves towards step 5 and it forms the basis of the list of amends for steps 8 & 9.

- Admitted to God, to ourselves, and to another human being the exact nature of our wrongs.

This step seems to involve a lot of what will be required to make the previous one effective. It’s no good just having a clear model of your wider recovery goals if that model is too much constructed in an over-dominant left hemisphere state – an over-certain self-constructed reality. Admitting it to God, on the account of God given above, would amount to checking your model of the situation against that of your more integrated self. In practice that might mean dwelling in the silence of prayer or meditation and listening for aspects of your own recognition that it might not be accurate. Others are also a great resource in providing a more objective view from beyond a potentially obsessed state.

Again your reflections around step 5 are pretty much spot on. The steps are progressive and don’t really make much sense individually as each one is designed to build on the work done in the previous one. It is an almost Gestalt-like process needing the sum of the previous work to make sense of the collective whole. As you have rightly pointed out, there are always and also external factors that enable the Gestalt moments that can and will occur. Put together the written inventory, higher power, and empathic other and you have a very powerful recipe for a higher/more objective view point and potentiality to move beyond attachment.

Step 5 is a very proactive process involving both the sponsor and sponsee sharing their experiences. On one level it’s a kind of confessional exercise and the beginning of a process of forgiveness. On another level its more about finding the real self amongst the defense mechanisms and hackneyed narrative of the false self. I have often found the paranoid networks created from delusional resentments tend to crumble as a result of this process. Something written down, then subsequently shared with another begins to loosen its power in the face of objectivity.

- Were entirely ready to have God remove all these defects of character.

- Humbly asked Him to remove our shortcomings.

This seems to mean, again, that having fully recognised the difficulties of overcoming addiction, we recognise that it will not be sufficient to merely try to impose one will or plan that will resolve that position. Instead, we will need to reframe it. The humility involved might also be the recognition that we do not have things rightly framed to begin with, and that we will need to continually adjust our understanding of how the long-term integrative goal of overcoming addiction can be achieved.

“Reframing and humility” are very common themes throughout all the steps. The serenity prayer does encapsulate this particularly well and is constant reminder of the maintenance work that will need to be done to “reach and sustain the long-term integrative goal of overcoming addiction.” Although the programme does suggest that we never fully overcome addiction and it is a life long journey, I am somewhat ambivalent about this.

6&7 are a direct extension of the work culminating in step 5. I have been asked about these steps on lots of occasions so have developed, what I see, a fairly simple answer. How I see it 6 is about all the things you are doing, thinking and/or believing that are probably not going to be conducive to your recovery. 7 is about all the things that maybe you will need to do to make your recovery probable and sustainable that you currently, for whatever reason, aren’t doing. The thinking goes that because these things are so firmly embedded within your psyche you are not going to be able to remove them by will power alone.

I question whether these things are ever fully removed or is it that as we meet new situations, that we used to deal with using defects and/or shortcomings, we now have choices and alternative mechanisms we can adopt. Maybe the default position is to revert to type but every situation you encounter from here on presents you with learning and resilience building opportunities.

- Made a list of all persons we had harmed, and became willing to make amends to them all.

- Made direct amends to such people wherever possible, except when to do so would injure them or others.

These two steps involve the recognition that integrating addiction is not just a question of working with our own individual relationship to our desires and goals. It is also a matter of moral and social relationships. If an addiction has had negative effects on others (which is very likely) then those others play a large part in representing both the conflict in ourselves and the possibility of healing it. By making amends we might gain the forgiveness of others and thus gain important positive feedback that will help our own healing process. Even if they don’t forgive us, we may still have got closer to reconciling our own inner construction of that person with our own sense of guilt.

In relation to the Middle Way, this is a reminder of the way the absolutes that we are trying to avoid on either side of the Middle Way are socially reinforced. An addict is very likely to have been caught between two sets of socially reinforced absolutes: fellow addicts pressurising them to join the addiction and the rest of society, often including close relatives and friends, urging them to give up the addiction. Such a conflict can only be overcome by reframing and seeing recovery as good for both oneself and others. But others might very well doubt the sincerity of the move towards recovery. Practice over a period of time shows integrated intentions and build up our capacity to avoid both extremes in any practice of the Middle Way. For the addict, ‘making amends’ (i.e. presumably exerting practical effort to create the basis of better relationships) could be the evidence that others need of actually being able to stay in the middle, no longer oscillating between the grip of addiction and merely willful attempts to give up.

I like your contextualizing here, for most their addiction will have had quite a profound impact on, not only themselves, but their loved ones and wider community. Like you’ve said it’s kind of like the butterfly effect in chaos theory, the addict may find themselves caught between lots of sets of, what are often, very fragile, “socially reinforced absolutes.” The whole thing collapsing as their addiction progresses, a process that often escapes their sense of accountability and responsibility. In order to, as you say, “reframe” this, we need to develop an empathic prospective, by learning to understand the impact the behaviour has on others, and open the self up to the objectivity that this will hopefully entail. Lots of people, including myself, have experienced OCD almost autistic-like thoughts and behaviours well before taking any drugs. OCD/autism being very much about control, absolutes and life threatening fear of the unknown. The steps, and especially step 4 onwards, help to create a less black and white/either or/absolute landscape and begin to give the person the confidence, capacity, support network and competence to inhabit it without needing substances.

It is very much a middle way position aiming to create an absolutes free landscape where risks can be taken, mistakes can be made and, when necessary amends can be given.

Making a list and subsequently making amends is a set of actions designed to put right wrongs you have caused. I always say to sponsees that they have created loads of you shaped holes in the universe that they will need to go back and repair. Staying clean and sober is an amend within itself and quite a lot of people I have made amends to have said as much. Making amends is really really powerful and often ends in tears in one way or another. I believe it helps us in the process of becoming forgivable and it also gives the people around us an opportunity to say to us what it was like for them.

Maybe amends are also a kind of rite of passage in the growing up journey of recovery. It’s the new non-using grown up identity I’m claiming becoming a responsible citizen and declaring the old self dead. Once you’ve started to make amends it’s going to be really difficult to go back.

- Continued to take personal inventory, and when we were wrong, promptly admitted it.

The ‘inventory’ mentioned in step 4 obviously needs to be maintained if the recovery is to be integrated. Integration is largely achieved over time, and involves the recognition that our states vary but that the goals they represent can be fulfilled better in a wider and more consistent set of purposes. One needs to keep that set of purposes clear.

The need to admit when we are wrong is a key element of Middle Way practice, and the main way in which we avoid absolutisation. Admitting we are wrong allows alternative views to come into our awareness – ones that we might have repressed ore rejected up to that point. By doing this we gain the ability to reach new understandings of ourselves and others and thus move beyond the narrow assumptions that characterise addiction.

10 is steps 8&9 in practice on a daily basis. It’s the acknowledgement that we are human after all and we will continue to make mistakes. The key will be to make and keep each 24 hours as manageable as possible. We don’t want to be carrying things over and we want to learn to shine the light on our mistakes and do something about them as soon as possible. It keeps our house clean, stops things building up and cuts down any reasons we may pick up to use.

It helps to maintain the social scaffolding and recovery oriented inner/outer landscape necessary for the changes taking place to move into and become unconscious behaviour and thinking patterns. One does indeed “need to keep this new set of purposes clear”, but they will also need to use daily inventory taking to help with the continued transition from a world of dependency towards autonomy. In many ways they will be growing up probably for the first time, at least since adolescence, and learning how to master the new, and much more acceptable, human being and life they are trying to create.

- Sought through prayer and meditation to improve our conscious contact with God as we understood Him, praying only for knowledge of His will for us and the power to carry that out.

This step returns to the recognition of God in steps 3, 5, 6 & 7, but seems to be making the point that the greater open awareness represented by God here is not just a tool for overcoming addiction. Rather it needs to be the basis of a lifetime’s practice if a slide back into the addictive mind-set is to be avoided. Again, the ‘as we understood him’ emphasises God as an experience or as an archetype rather than as a supernatural being issuing revelations. We gain our power to carry on and sustain recovery from integration with those otherwise repressed elements of our own experience.

This need to switch to a longer-term mode again reflects a necessary element in any Middle Way practice. It is quite possible to move into what you at first think is the Middle Way, but turns out on closer inspection to have further dogmatic elements, so that you need to maneuver yourself a bit more to get off the sandbanks and back into midstream. It’s only as our awareness is allowed to become a bit more subtle and attuned that we might become aware of assumptions we were making that might still, in the longer-term, have taken us back in the direction of the extremes we were avoiding. In the case of a recovering addict, that need for further maneuvering in the light of gathering self-awareness may be particularly acute, as the polarising effects of addiction can be so deeply rooted and socially reinforced.

I really like your observation here where you talk about god as an experience rather than a supernatural being dispensing revelations. Although, for some, the higher power will be more supernatural it will involve revelations being revealed, for me it’s much more experiential and proactive. As I’ve said, I’m not a particular fan of god, either as a word or in the very loaded context it’s used far too often. For me “god or godliness/the divine, etc.” is in everything and everywhere. Because, by now, I’ve changed pretty much everything about me, I see and experience things very differently. Probably since childhood, almost everything I’ve done has been on the basis of me and what can I get out of it. My modus operandi was all about control and, as you say, this was very much deep rooted and socially reinforced. If we’re not careful and, I suppose, aren’t embracing a middle way philosophy, the steps and the programme can and often will become a further extension of dependency involving just as much fundamentalism and dogma as any extreme religious belief or addiction to substances. Prayer and, for me more importantly, meditation enable us to continually centre ourselves, stay humble and open ourselves up to a broader horizon.

11 keeps us spirit centred. It emphasises the need for discipline, self reflection, meditation and prayer/continued contemplation. I also believe it encourages us to become seekers of wisdom and spirituality and recognises that beliefs, faith and attachments can change. All the steps have prepared us for this point and the transition to step 12

- Having had a spiritual awakening as the result of these steps, we tried to carry this message to other alcoholics, and to practice these principles in all our affairs.

Given my Christian background, the wording of this step reminds me rather of the Acts of the Apostles, but it also seems important to try to put aside such associations and try to imagine what they mean to someone recovering from addiction. Given the sheer enormous difficulty of recovering from a serious addiction, and the amount of reframing involved, to describe recovery (or the transformation of attitudes that allowed recovery) as a spiritual awakening is probably no exaggeration. Carrying the message to other addicts does not necessarily mean evangelisation in the gross forms we may associate with some forms of Christianity, but rather may be motivated by a genuine urge to help others whom we know, from our own experience, to be suffering.

“To practice these principles in all our affairs” again makes it clear that the 12 steps do not merely imply a method for overcoming addiction, but draw on a larger view of life. This view of life seems close to the Middle Way in all sorts of ways, even though one has to imagine the principles of the 12 steps in practice to draw out those Middle Way elements. The language seems clunky, but one has to bear in mind that the first creators and users of the 12 steps probably had no better language available to them with which to express their practical insights than the language of Protestant Christianity.

Everything has prepared the person for this point which, I believe, is all about becoming of service and maintaining yourself to carry on. Over the years I’ve come to see “the addict/alcoholic” in just about everyone I come across so I always try to be in a position where I can be of service should the need arise. This does involve “practising these principles in all my affairs” because I want the service I offer to be authentic, attractive, empathic and engaging. Otherwise it will be controlling, fake and far from appealing.

Although for many, and especially in early recovery, step 12 does take on an urgency and can become very evangelical. It can also give some people permission and ammunition to become very closed minded, authoritarian and arrogant as they develop an “it’s the only way” type message. I think that’s why one of the traditions talks about attraction rather than promotion, after all we do tend to move towards things we find attractive and either rebel against or move away from things that are rammed down our throats.

This, in my humble opinion, is what I call modelling recovery and does have a definitive middle way air about it.

Conclusion

As Marc Lewis explains in ‘The Biology of Desire’, addiction consists in a set of feedback loops between the striatum in our lower brains and the frontal cortex. These loops link our representation of our goals and of the state of affairs around us to dopamine rewards that reinforce behaviour that addresses certain conditions. These are entirely normal loops that emerge in the course of learning and adapting to our environment, but in the case of addiction, the loops become deeply entrenched and gradually automatised, excluding other possible modes of behaviour. We then lose the flexibility that we need to continue responding to changes in our environment. Lewis’s account thus highlights how we are all addicts to some extent – just some more than others. We all have entrenched habits linked to rigid beliefs about our goals and conditions: it’s just a matter of how much. Those rigid beliefs form the extremes on either side of the Middle Way, the positive and the negative absolutisations.

Purely by virtue of their track record as ways of effectively addressing addiction, the 12 steps must offer a way of addressing these entrenched habits and beliefs. Thus it seems that we can all benefit from them, whether we regard ourselves as ‘addicts’ in any sense or not. Wherever we find rigid thinking or unhelpful habits in ourselves we can adopt the basic procedure that it seems the 12 steps are pointing at: reframe, realise it’s not just a matter of wanting to change or being unable to change, be receptive, reconsider your assumptions, face up to the full difficulties, develop and clarify sustainable goals, address the issues in your relationships with others, and commit yourself to continuing to do this in the long term. The 12 steps seem to have a great deal to teach us, and this seems to be rooted in much wider insights than might first appear.

I do believe that everyone could benefit from the 12 steps especially in these days of consumerism, selfhood, reductionism and instant gratification. Maybe the language needs changing, after all they were written 70-80 years ago in very different times with very different social circumstances. Personally I would like to find an alternative to god/higher power because of the sheer amount of people I see who just cannot get used to it.

Marc Lewis and people like Bruce Alexander and Maia Szalavitz are beginning to challenge some of our long held shibboleths around the abnormalisation of the human condition and, in particular, learning/neuroplasticity. Unfortunately it has become a diametrically opposed argument where a middle way has yet to evolve. Personally I do believe that both camps are far from incompatible, both probably have far more in common than they have differences. Yes looking at things as diseases is pretty much absolutist and you can’t really go anywhere with a religious interpretation of god/higher power. But, and this a big but, there are lots of things within the fellowships and the 12 steps that could be contextualized within the new thinking. All agree that things like connection, giving, learning, taking notice and keeping active are the essential components of recovery, no matter what it is we are recovering from.

My major concern around 12 step ideology is how it has been and continues to be corrupted by people marketing it as an evidence based “treatment”. My view is that it should never involve money. If you are going to invest in any kind of treatment system there are loads out there to choose from. It should have no part in treatment except to offer access to meetings. It should have no part in the politics of substance use treatment politics and/or commissioning and should be left well alone to do what it does best through peer support and self help.

Picture: Annie Besant ‘Greed for Alcohol’

The act of creation

I’ve been thinking recently about creation in human experience, and also how this relates to the symbolism of creation in the Bible. I’m indebted to Iain McGilchrist here, who, in ‘The Master and his Emissary’ points out the difference between left hemisphere and right hemisphere forms of creation: I will call them reproductive and mimetic forms of creation. The more I reflect on this difference the richer it seems.

In the reproductive form of creation, some kind of idea, plan, or copy (whether mental or physical) of what is to be produced already exists. A new version of that copy is produced.

However, in the mimetic sense of creation, something already exists that may have a closer or more distant resemblance to the thing to be created: it may just be ‘raw material’ that is to be shaped, but in accordance with how it already is. The existing materials are recombined so as to produce something new that was not previously combined in that way, whether in the object itself or in the mind of the creator.

The crucial differences between these forms of creation depend on what is going on in the mind of the creator.

In the reproductive sense of creation, there are clear goals and representations of what is to be created, and the process of creation is merely to reproduce those goals as precisely as possible. The representations may or may not include an actual copy of the thing to be produced already in existence. A construction engineer building a bridge from a set of painstaking designs in creating in this sense, as is a factory production worker who merely controls a machine that is pre-set to reproduce identical plastic parts over and over again. In this sense of creation, the left hemisphere is heavily dominant.

Reproductive creation follows a positive feedback loop in which an idea is fixed on, a copy of that idea is constructed, and then the constructed thing reinforces the idea. However, reproductive creation will only actually succeed to a certain extent. The plastic parts may appear identical, but will have microscopic variations. The bridge may follow the specification as precisely as possible, but there will be at least some small divergences from it. However, the mental state accompanying this kind of creation focuses on the goal of copying, and will either be frustrated by a lack of exactness in the copying or will deny that there is any such lack, re-interpreting the creation to fit the idea and pretending in ad hoc fashion that it was intended to be like that all along. Any divergence from the plan, if it is admitted, is a failure. The view of the world adopted is one where it is assumed that it is possible to copy exactly because there is an absolute relationship between the specification and the creation. Whilst it may be admitted, on philosophical enquiry, that the copy in the plan is not exactly the same as the created thing, the reproductive creator will insist on the absoluteness of the relationship. This relationship can be called isomorphism from the Greek for ‘same shape’.

In the mimetic sense of creation, on the other hand, there is no expectation of any isomorphism between a plan or a previous model and what is created. Rather it is accepted that both the form of what is created and its meaning to us will depend on various variable factors: the nature of the materials, the mental state and expectations of the creator, or other incidental factors that contribute to what is produced. It is not that the creator will lack plans or intentions, for these will always have to be present to some extent for the activity of creation to occur at all. However, it is accepted that the creation will in some respects have a life that is independent of the creator. Different goals may emerge in the process of creation that were not envisaged at the beginning. A wider harmony and integrity will be sought for the creation which is only partially in line with any wishes the creator may have started with, also responding to the conditions that arose in the process of creation.

In contrast to the positive feedback loop involved in reproductive creation, mimetic creation involves a negative feedback loop. An idea of what is to be made is put into operation, but differences between the idea and the creation are not seen as failures, rather as new conditions to be learnt from and responded to. In this way the idea of what is being created continually changes along with the thing being created.

The mimetic sense of creation is obviously one that applies to works of art, following the senses discussed by Samuel Taylor Coleridge and Erich Auerbach. It also applies to parenthood – at least if it is pursued with wisdom rather than with inflexible plans for the child. Mimesis is obviously the embodied type of creativity. It is a type of creativity pursued with an active and integrated role for the right hemisphere, taking new conditions into account as well as the left hemisphere’s goals and representations. We tend to describe people as ‘creative’ who have learnt to manage the process of mimetic creation with confidence.

I don’t want to imply here that reproduction is necessarily bad: it is just limited when compared to mimesis. The problem with reproduction seems to be when it is absolutised: when we expect copies to be exact, and plans to be precisely reproducible. There are some horrendous examples in history of big plans that were put into operation with hardly any consideration for the conditions: perhaps the Tanganyika Groundnut Scheme is the most astonishingly arrogant and incompetent example I have come across. Mimesis, on the other hand, is not only a quality of the best art, but also the best political proposals and the best engineering projects, among many other things.

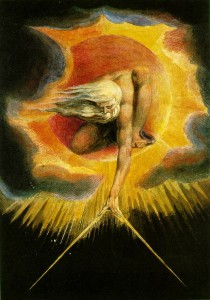

If you apply these ideas about Creation to God’s creation of the world in Genesis, they can be related to the debate about what sort of creation Genesis is describing. Did God simply have a plan that he put into operation regardless? If so, we could read the Creation story as a left hemisphere fantasy of the total and precise enactment of a plan, based on total power. This way of thinking seems to be implied in the classic Christian interpretation of the Creation as ex nihilo – that is, as creating something out of nothing. Blake’s famous ‘Ancient of Days’ picture depicts this kind of creation.

But the text begins “In the beginning God created the heavens and the earth. The earth was a vast waste, darkness covered the deep, and the spirit of God hovered over the surface of the water.” (Gen 1:1-2), which can on the contrary be read as indicating that earth, ‘the deep’ and water already existed, and were merely formed by God. This interpretation would fit the influence of Babylonian and other near eastern creation stories on this one, as the other stories all involve prior existent matter.

If we try to let go of all the metaphysical claims and associations with Christian (and Jewish) dogmas in the Genesis story, we can read it archetypally and in accordance with human experience, simply as an inspiring symbol of creativity, with an archetypal God as a cosmic artist. God does have plans, but he also has raw materials and unexpected conditions to respond to. He pauses each day after making each new set of things before continuing, suggesting that he wasn’t just putting his plans into operation without reflection. What’s more, if you’re creating something as complex as life, you must expect it to respond in unexpected ways: as Adam and Eve are depicted as doing. For more on the Eden story, see my previous post, ‘Reconsidering the Fall’ (and also don’t miss Emilie Aberg’s excellent comment on that).

What is wisdom?

Wisdom is our most important practical quality, but it often seems to be more the basis of fantasy than cultivation. Given an educational system that will barely mention it, it is hardly surprising if wisdom to many people primarily means wizards with long beards and flowing robes. If we have not even reflected how far we have it ourselves, it’s not surprising if it’s projected onto distant figures. But wisdom is about how you make judgements: about, say, what to eat for lunch, or how to respond to that irritating colleague, or whether to spend the evening reading or browsing the internet. We all have it to some extent, and we lack it in other respects.

Wisdom should not be confused with knowledge. It is not about what you know, unless it’s about recognising how little you know (as Socrates famously said, he was only wise in the sense of recognising his ignorance). That means you could conceivably be quite wise with little education. Nor is wisdom an automatic benefit of age: you only have to reflect on the narrow-mindedness into which some older people sink to see that.

Instead, I want to suggest that wisdom is a quality dependent on how well we use the experience we have. If we only interpret experience in terms of narrow assumptions, that experience will be useless to us, and will not enable us to learn. Instead, experience will only re-confirm the assumptions we already carry. That’s the positive feedback loop we can get into if we are fixated on ‘knowledge’ or ‘truth’, believing that we have these things and then making our experience fit.

To become wiser, then, we will need to avoid these kinds of fixed beliefs, whether they are positive or negative, but investigate closely, even amongst sets of beliefs we otherwise reject, for ideas that are relevant and helpful. That means that, for example, the wise socialist will try to learn from conservatives even whilst rejecting dogmatic elements of conservatism (and vice-versa). Or if you have a strong belief in yourself as, say, destined to be a successful artist, but end up rejecting that belief as unrealistic, to cultivate wisdom in relation to that belief you will search around for aspects of that artistic aspiration that you can carry forward into other visions of your life.

Wisdom is often contrasted with compassion, but I want to suggest that the two are only conceptually distinguished: in practice they are inseparable. That’s because ‘reason’ is inseparable from ’emotion’, and it’s only a series of unhelpful cultural and philosophical habits that makes us often separate them too sharply. To be wise is to be compassionate, because whenever you challenge fixed beliefs about a person, you also challenge fixed feelings about them. By entering into more open beliefs about them, you also enter into more open emotional responses. By developing provisionality you also develop love, in a sense that avoids both hatred and possessiveness. Of course, the development of wisdom can only continue from wherever you start in emotional as well as cognitive terms, and someone who finds empathy difficult will not magically find it easy because of greater wisdom: but they will be more compassionate than they were before.

I’ve recently completed a video that explores the theme of wisdom in terms of the integration of belief. The integration of belief is simply a term for that process of sifting absolute beliefs from more helpful provisional ones – the process of developing wisdom and compassion. Here’s the video.

Picture by Ferdinand Reus (Wikimedia Commons) CCSA 3.0

Middle Way Thinkers 9: Jean-Paul Sartre

Jean-Paul Sartre (1905-1980) was a French philosopher, novelist, dramatist, and public intellectual. As befits the cultural prominence of philosophy in France, his funeral cortege in 1980 was followed by 50,000 people. Generally the philosopher who best fits the label ‘existentialist’ (which, unlike Heidegger, he used himself), Sartre was in many respects a bold and original thinker – he was concerned with imagination, action, and practice as much as theory, and above all focused on human experience as our source of information (phenomenology).

To my mind Sartre’s important contribution to Middle Way thought lies in his unflinching recognition of human responsibility. Very much a moral philosopher, Sartre argued that we are not only responsible for how well we follow moral rules, but also for the rules themselves. By selecting and obeying such rules, we give them their moral justification and validity. In his famous example of Abraham from the Old Testament (also used by Kierkegaard), Sartre pointed out that when Abraham heard God telling him to sacrifice his son, he could not justifiably pass on the responsibility for the deed to God – for it was Abraham who was responsible for interpreting what he had heard as the authoritative voice of God.

In this recognition of our responsibility for our judgements, Sartre contributed an important part of the case against metaphysics, and against the doleful but dominant insistence that it is inevitable still found today in much philosophy and science. But whatever we experience, whether it is a big voice in the sky or a scientific observation that seems to neatly fit a theory, there are always alternative possible interpretations, and thus we can never be compelled to accept one necessary interpretation. If we remain consciously unaware of alternatives but might, with considerable effort, have become aware of them, we also remain responsible (though, to clarify Sartre, I would say that we do so only to a small degree). Humean naturalism, which asserts that we can’t help what we believe, is shown up as dogmatic by Sartre’s recognition of our responsibility.

Unlike previous philosophers and theologians who attributed our responsibility to a metaphysical soul, Sartre did not seek any justification for it beyond experience. We are responsible because we experience responsibility. However, Sartre also recognised conflicts in that experience: we often find that responsibility uncomfortable and cannot face up to it, so we slip into the ‘bad faith’ of pretending that we are not responsible, because God told us or the universe itself told us, or we couldn’t help it or we were just following orders. If we can face up to our responsibility we can be ‘authentic’.

Sartre also did recognise that our choices are made in a context of certain conditions that are already set for us. He called this ‘facticity’. At every moment when we make a judgement, the openness (or ‘nothingness’) of mere potential is closed and becomes facticity. But then we are faced with yet another choice and another. Sartre pointed out that our choices have to be constantly remade for as long as they take to be put into action: for we could always potentially reverse our decision.

The focus on judgement in Middle Way Philosophy owes much to Sartre. Like Sartre, I think that it is the quality of a judgement itself, rather than its content, that makes it better or worse. However, it must be added that the content does have a big effect on the quality of the judgement, together with the character of the person who makes it. Thus, for example, a judgement to commit murder is extremely likely to be a bad judgement because it’s only likely to be taken by someone who ignores or represses their awareness of many of the consequences of committing murder. Sartre put a lot of emphasis on what is often taken to be a form of relativism (or subjectivism): that is, denying that there are any absolute rules that make one choice better than another. But I think it is debatable whether Sartre should be read as a relativist at all. For him an authentic (and thus, we can surmise, integrated) judgement is better than one made in bad faith that does not recognise our responsibility. Such arguments will apply in science as well as in the generally accepted moral realm.

There are several less helpful aspects of Sartre’s thought, though, that seem to take him further from the Middle Way. One is his rejection of psychology and public disagreement with Freud. He seems to have been understandably reacting against Freud’s determinism, but in the process also rejected the concept of the unconscious, which could have been very helpful to him in developing a more psychologically adequate account of ‘authenticity’ and ‘bad faith’. Another is his long-term flirtation with Marxism, although he did not join the Communist Party and later described himself as an anarchist. Nevertheless, Sartre has been blamed by his critics for leading others towards Marxism without sufficient scrutiny of its dogmatic assumptions and authoritarian practice. It does seem that, without a very developed psychological idea of what an authentic judgement would look like, Sartre sometimes seemed to make judgements (like that in favour of Marxism) that were more the product of an individual choice made in a vacuum than a careful scrutiny of conditions.

Sartre tends to stress the openness of our responsibility at the expense of balance. Though he tries to avoid metaphysical assumptions, he does not seem to be sufficiently aware of the dangers of negative metaphysics, and sometimes, arguably, he slips into it whilst reacting against traditionalist absolute positions. Thus he may not come across very much as a Middle Way thinker in his general style and approach: he is more of an enfant terrible. Nevertheless, Sartre’s contribution to our understanding of the Middle Way in respect of judgement can hardly be underestimated.

Link to index of previous ‘Middle Way Thinkers’ blogs