When polarities become extreme, we need the Middle Way more than ever, and the election of Donald Trump as US president polarises not just the US, but the world. That’s not just a polarisation between those who voted for him and those who desperately oppose him. Amongst those who do not support him, some urge adaptation to new ‘realities’, others eternal resistance to the normalising of this unpredictable new power in the world. The new US administration currently seems to offer horrible visions for the future: galloping global warming, mass round-ups of US immigrants, potential abuse of executive and legal power in the US on an unprecedented scale, and the untrammelled exercise of autocratic power by Russia.

What is the Middle Way in response to such? It’s not a compromise or just an appeal to moderation. As always it requires us to go back and rethink our starting assumptions. The Middle Way involves the identification and avoidance of absolute assumptions, both positive and negative, and in many past political conflicts, those absolutes have been ideological ones. Bush caused conflict because of the inflexibility of his neo-conservative view that liberal democracy could be imposed on Iraq. Reagan and Thatcher caused conflict because of their inflexible faith in market mechanisms.

But Trump isn’t like that. He is not an ideological absolutist. He has changed party at least five times. Has been recorded contradicting himself on numerous occasions, for example on this video. Nobody can accuse him of being inflexible in terms of ideology. He crosses the lines between traditionally liberal positions (e.g. investing in infrastructure) and traditionally right wing ones (e.g. tough on immigration). So does that mean that Trump is a pragmatist who exemplifies some version of the Middle Way between ideological extremes? Unfortunately not. His positions are so variable because they apparently don’t even have a basic level of reflectiveness and consistency behind them of the kind that we generally expect from successful politicians. Far from being stuck in a dogmatic, left-brain model of how the world is or ought to be, he apparently hasn’t even reached first base in assembling a basically coherent ideological view of the world about which one might be dogmatic.

So what is Trump’s absolutism? From the evidence available to me, it seems to be just egoism. His view of the world is that he can’t be wrong or acknowledge weakness regardless of his inconsistency, and the beliefs that he holds to absolutely are just that what Donald Trump believes in right now is right. That makes him an ultra-pragmatist in the worst, not the best sense – that is, of someone who will follow political expediency based on very narrow values. He doesn’t flip-flop because he’s so integrated that he’s provisional, but rather because he’s not even integrated enough to hold an ideological position.

What about the thinking of those who voted for him? The dominant absolutism here seems to be one of nostalgia or idealism about ‘making America great again’, together with absolute rejection of ‘the establishment’, crudely identified, regardless of their actual merits or demerits. You don’t have to go into any further social or psychological profile of Trump voters to identify that tendency. These feelings seem obviously to have been absolutised, because they have not been weighed up against any assessment of the strengths and weakness of Trump’s policy or personality. Of course I don’t know whether or not that’s the case with every Trump voter, but there seems no reason to question it as a reasonable generalisation.

So, of course, Trump isn’t absolutely wrong, and nor are his voters. But I agree with his ‘liberal’ critics in being extremely concerned about the situation. His level of dogmatism is not even grown-up, to the extent that many people in the world have no idea how he is likely to act or how far he means what he said in the campaign. The Middle Way is quite compatible with overwhelming confidence in one position or another, precisely because we have recognised that we have no justification for absolute positions, and therefore a respect for evidence and the power of coherent provisionality and a clear rejection of absolutism. That confidence has to be politically opposed to Trump.

But what about the ‘you can’t normalise this outrage’ argument verses the ‘realpolitik’ argument? The Middle Way always requires us to accept the conditions, but one of those conditions is the tendency for people to socially normalise what was once considered utterly unacceptable and then forget that they have done so. That can work positively to make people forget how much better today’s world is for, say, for ethnic minorities, women, children or LGBT people than it was even 50 years ago. However, it can also work negatively to enable the persecution of minorities to become normalised when it wasn’t before, as it did in Nazi Germany. We always need to maintain a wider awareness of the possibilities than the people in power would like us to have. So, recognise the reality of Trump but don’t normalise him. Don’t let him take over your consciousness too much. Take breaks from politics to get perspective. Remember the standards you had before Trump.

As a British person, I’m not in a position to contribute to bringing down Trump, but he is nevertheless likely to affect my life profoundly. I’d like to support all Americans who oppose him, and wish you the best of luck in removing him as soon as possible (whilst, of course, trying to engage positively with the Trump voters). That’s a politically partisan wish, but not one coming from unreflective absolutism. As far as I can see it demonstrates an application of the Middle Way, which is a method of dealing with both internal and external conflict without false neutrality. Your understanding of the Middle Way, of course, may be different because it depends on the conditions you are addressing in your life. You could conceivably reach a different conclusion whilst sincerely and reflectively applying the Middle Way. But since most readers of this blog are likely to share many features of the overall cultural and political context of the modern West with me, I doubt it.

Related: Introduction to Politics and the Middle Way

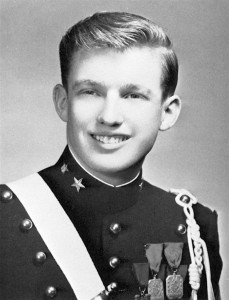

Picture: Donald Trump as a young man (public domain picture)