We do not know whether or not Jesus was resurrected on the third day, but we do experience a more profound and much more common kind of resurrection, when out of every intransigent problem springs hope. Of course, we maintain many kinds of hope, but the most powerful is that which comes out of apparently lost situations, which are only a matter of despair because of the way we have been framing them. The resurrection stands for not only a reframing of death, but a reframing of all other human suffering.

If, indeed, as the gospel narratives insist, Jesus was resurrected, it was an odd kind of resurrection. For the resurrected Jesus, it seemed, delighted in teasing people’s plodding certainties when resurrected even more than he did in life. Instead of confronting his disciples directly after his resurrection, he left them to discover an empty tomb and to be told the news by an angel[1]. When resurrected, he appears and disappears abruptly and unpredictably[2]. He is often not recognised at first, but only in retrospect or when he performs a characteristic gesture[3]. He can enter a room with a locked door[4]. He is at pains to point out that he is not a ghost, but a corporeal being who eats, can be touched, and bears the physical marks of the crucifixion[5], but in other respects he hardly follows the normal habits or limitations of an embodied person.

All of this suggests overwhelmingly that the resurrection of Christ is not a glorious certainty that we should believe in as a historical event, but rather a glorious uncertainty. When all seems lost in the old paradigm, when the paradigm shifts to a new way of understanding, we should only expect the unexpected. In amongst the possibilities remains the likelihood that all is lost, but there also remains grounds for hope – that even the most intractable conditions may yield when we are prepared to change our view of them. Incurable cancer may clear up. The certainties of Newtonian physics can give way to relativity. People separated by the entire mass of the earth can communicate instantaneously without leaving their bedrooms. A man from a race once enslaved can become president.

The new grounds of hope arise from the integration of energy associated with possibilities that were previously repressed. That means that, in archetypal terms, resurrection is created from the integration of the Shadow. That process of integration of the Shadow is represented in the non-scriptural Christian tradition of the harrowing of Hell. Between the crucifixion and resurrection, it is traditionally believed, Christ descended to Hell, bound Satan, and rescued the Old Testament prophets who had been damned purely due to original sin, regardless of their personal merits. One can see this, of course, as a medieval theological invention designed to explain away an awkward implication of atonement: that nobody who lived before Jesus could be saved, no matter how good or faithful. However, that development also has a positive symbolic function which we could perhaps interpret rather as removing the apparatus of original sin and damnation entirely: when we engage in the integrative mediation represented by Christ, we are freed from the Hell of the constricted ego.

For Jung, the harrowing of Hell has a close relationship with the psychological function of the resurrection:

The present is a time of God’s death and disappearance. The myth says he was not to be found where his body was laid. “Body” means the outward, visible form, the erstwhile but ephemeral setting for the highest value. The myth further says that the value rose again in a miraculous manner, transformed. It looks like a miracle, for, when a value disappears, it always seems to be lost irretrievably. So it is quite unexpected that it should come back. The three days’ descent into hell during death describes the sinking of the vanished value into the unconscious, where, by conquering the power of darkness, it establishes a new order, and then rises up to heaven again, that is, attains supreme clarity of consciousness. The fact that only a few people see the Risen One means that no small difficulties stand in the way of finding and recognising the transformed value. [6]

The prime Christian virtues are faith, hope and love: but all of these are founded, not on absolutising beliefs, but on the recognition of uncertainty. Faith, in an experiential sense rather than the sense of absolute belief, depends on embodied confidence. ‘Doubting’ Thomas was not wrong to seek embodied experience as the basis of his faith, and Jesus treats his need with understanding[7]. We might be better to call him Faithful Thomas. Faith projects that confidence forward into what we have not experienced yet, but hope goes further in offering possibilities that we could not justify faith in. Love (or charity) depends on maintaining a flexible and rounded view of others, who are neither instruments nor obstacles to us, but rather persons. All three of these virtues, then, are dependent on provisionality, and none of them can be practised without the Middle Way. But hope is the most forward of them all, the most alive to mere possibility. Hope springs most of all from the flexibility of the imagination, and is constrained by the iron repression of belief. That is why it is so ironic that the resurrection, so much a symbol of hope, should have become an object of metaphysical belief and thus undermined hope.

The above is an extract from Robert M. Ellis’s forthcoming book ‘The Christian Middle Way: The case against Christian belief but for Christian faith’.

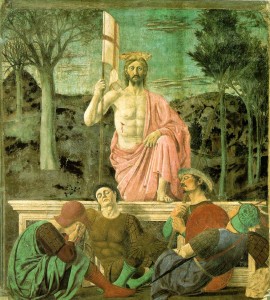

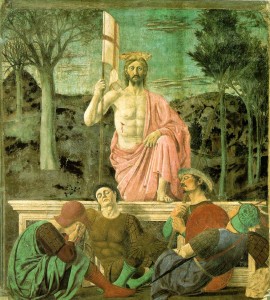

Picture: Resurrection by Piero della Francesca

References:

[1] Mk 16:1-8; Mt 28:5-7

[2] Lk 24:31,36 & 51

[3] Lk 24:16; Jn 20:14; Jn 21:4

[4] Jn 20:26

[5] Lk 24:38-43; Jn 20:26-9

[6] Carl Jung (1958): Psychology and Religion, §149

[7] Jn 20:24-9