To the vast majority of Westerners, including me until recently, Chinese characters are just squiggles. But I have recently begun the study of Chinese, in preparation for a period working in China that should begin in a couple of months’ time, and found myself unexpectedly fascinated by the characters. If I had an expectation about learning the characters, it was that it would involve hard graft, trying to remember the relationships between random squiggles and meanings. But instead, if anything, it seems more like play, because it recapitulates the gradual assemblage of meaning we go through in childhood. Instead of graft, it involves a development of meaning connections that are accompanied by something more like delight. My progress has also been greatly aided by a delightful book called Chineasy, first created by a graphic designer called Shao Lan to help her children learn Chinese characters.

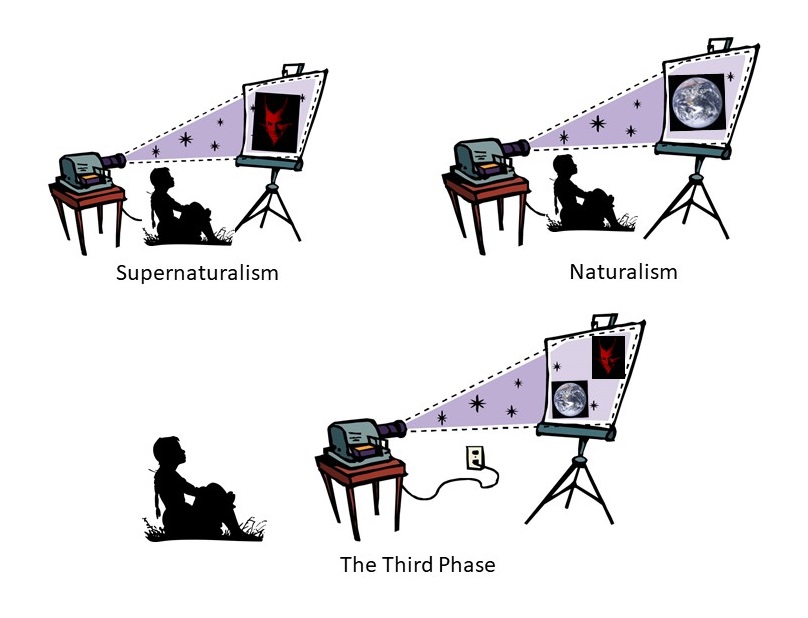

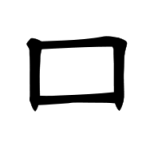

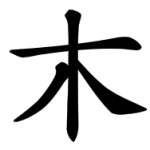

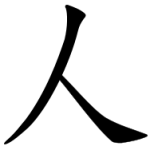

Shao Lan’s book makes clear how Chinese characters have developed out of what she calls ‘building block’ characters (which are not quite the same as the more commonly known ‘radicals’). These building block characters have all developed out of stylized representations of everyday, concrete things; the kind of things you would expect the ancient Chinese to represent first. These include terms like person, tree, fire , water, weapon, sheep, horse and tiger. Here are some examples:  on the left is the character for ‘mouth’ (kou), which looks a bit like a mouth except that it’s been squared off; on the right the

on the left is the character for ‘mouth’ (kou), which looks a bit like a mouth except that it’s been squared off; on the right the character for ‘tree’ (mu), which looks like a simplified tree with spreading branches and roots; and on the left the character for ‘person’ (ren), which you could think of

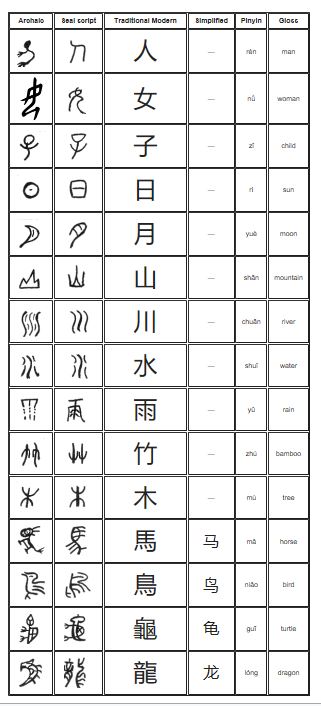

character for ‘tree’ (mu), which looks like a simplified tree with spreading branches and roots; and on the left the character for ‘person’ (ren), which you could think of  as a stick figure minus the head and arms. Some more examples of ways that modern characters have developed from early pictograms are given in the table at the foot of this blog.

as a stick figure minus the head and arms. Some more examples of ways that modern characters have developed from early pictograms are given in the table at the foot of this blog.

These basic building blocks are then extended to produce gradually more abstract terms. For example, put an extra root on the ‘tree’ character and you get the character for ‘origin’ (ben) – see left. The idea of an origin is a metaphorical development

more abstract terms. For example, put an extra root on the ‘tree’ character and you get the character for ‘origin’ (ben) – see left. The idea of an origin is a metaphorical development of ‘root’. Combine this character with an abbreviated person to the left of it and you get the character for ‘body’ (ti) – see right. The body is the root of the person.

of ‘root’. Combine this character with an abbreviated person to the left of it and you get the character for ‘body’ (ti) – see right. The body is the root of the person. Put three mouths together (presumably all offering different opinions), and you get the character for ‘quality’ (pin) – see left.

Put three mouths together (presumably all offering different opinions), and you get the character for ‘quality’ (pin) – see left.

It didn’t take long, as I began to engage with this learning process, for it to suddenly dawn on me that the composition of Chinese characters graphically illustrates the development of embodied meaning as explained by George Lakoff and Mark Johnson – a theory that has had a huge influence on Middle Way Philosophy as I have developed it in my books (especially Middle Way Philosophy 3, which is all about meaning). Lakoff and Johnson offer a radically alternative understanding of meaning to the mainstream ‘representationalist’ view that is still assumed in much philosophical and scientific thinking: one in which meaning is not based on a relationship between words and symbols on the one hand and some sort of assumed ‘reality’ on the other, but rather one in which we build up meaning through the links we make in our brain as we learn from early infancy, connecting words and symbols with embodied experiences. Their explanation begins with what they call ‘basic level categories’ and ‘image schemas’ – basic building blocks of meaning in which a particular common experience becomes associated with either a word itself, or an implicit connection between words. It then explains how these building blocks of meaning gradually get elaborated through metaphorical extension into more abstract terms. Crucially, to understand even very abstract ideas, we draw on our earlier layers of meaning-linkage: so, for example, to understand the concept of an academic field I draw on my understanding of ‘literal’ fields or other bounded ‘containers’, which connects this abstract idea to my most visceral, infantile experiences of putting things into other things that contain them (including my own body). This reflects what Lakoff and Johnson call the container schema.

Lakoff and Johnson’s theories are explained and evidenced in some detail in their works, but (although they give a range of examples) I have long felt the lack of some kind of ’embodied meaning dictionary’ which might assist one in working out how a particular word, symbol or term developed out of basic level categories and image schemas. Of course, there are also a number of possible problems with such a project. One is that there are probably no definitive answers as to how meaning developed in each case, just a range of plausible explanations – the main point of the theory being just to show that it must have developed in that way in general rather than to prove any specific example. Another problem is that the basic level categories, image schemas and metaphors obviously vary enormously in different linguistic contexts. Perhaps even the same or a similar term may have a different embodied sense for different people, depending on what the basic level categories were, how they have interacted and how the metaphors have developed.

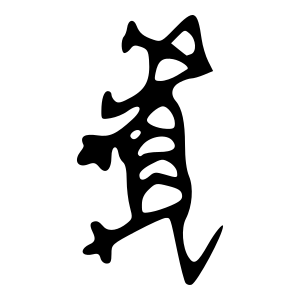

But Chinese characters seem to offer a kind of graphic record of this process of meaning development. The ‘building block’ characters can be readily identified with basic level categories: not necessarily our basic level categories, or even those of modern Chinese people, but those of the ancient Chinese who developed the characters. The associations between these characters that allow them to develop also depend on image schemas that allow connections of meaning between basic level categories in a particular embodied situation. If I’m an ancient Chinese person, I won’t just passively appreciate a ‘tree’ as a separate object, but probably chop it down and build a house out of it, creating a set of associated meanings that combine associations of timber, origin, foundation, and home. I won’t just contemplate a tiger as an object (early ‘Oracle bone’ version on right), but rather I’ll associate it with the bodily experience of fear, allowing the creation of characters that develop ‘tiger’ into words that refer to danger, as they do in modern Chinese. I’ll also combine the basic level building blocks in ever more complex ways dependent on metaphor, as in the development of ‘quality’ from ‘mouth’.

of timber, origin, foundation, and home. I won’t just contemplate a tiger as an object (early ‘Oracle bone’ version on right), but rather I’ll associate it with the bodily experience of fear, allowing the creation of characters that develop ‘tiger’ into words that refer to danger, as they do in modern Chinese. I’ll also combine the basic level building blocks in ever more complex ways dependent on metaphor, as in the development of ‘quality’ from ‘mouth’.

It has to be stressed that embodied meaning is our meaning as individuals, so this cultural record is only an approximation of the process by which meaning develops in an individual. Nevertheless, the parallels are striking, and seem to offer evidence in support of Lakoff’s and Johnson’s whole way of thinking. The relationship also offers much potential for improving language education so as to take into account the way in which we process meaning. A Ph.D. thesis by Ming-San Pierre Lu shows that this kind of approach leads to much more effective learning of Chinese.

In some ways the same development can be traced in the phonetic scripts that most of the rest of the world uses (such as the Roman script I’m writing in now), except that a disconnection obviously occurred early in the development of phonetic scripts, when pictograms began to be used to represent sounds. For example, the capital letter A still looks a bit like an upside-down ox, reflecting its origins in a Sumerian pictogram that then came to mean the initial sound used in the word rather than the meaning of the word itself. Since the relationship between sounds and meaning is largely abstract and conventional (except for a few onomatopoeic words), it’s very easy to lose any sense that the letters we use depend in any way on a base of embodied experience. That can happen in Chinese too, of course, where the characters are highly conventionalized, and doubtless the experiential basis rarely reflected on in practice. If a Chinese symbol only means an abstraction to a particular individual, its past historical development will make no difference. It’s learners of Chinese, probably much more than proficient users, who have the privilege of reconnecting with that experiential basis.

So how does this all relate to the Middle Way? Embodied meaning is closely related to the Middle Way, because acknowledging it can be a very useful element in practising the Middle Way and avoiding absolutisations. You can only make and believe an absolute claim if you assume that the language you use represents the world in some way, and that the claim you are making can thus be ‘true’ or ‘false’, rather than helpful or unhelpful in relation to experience. I don’t want to suggest for a moment that users of Chinese are any less prone to absolutisations than other linguistic groups. I have no evidence for that. I’d only suggest that they have a very helpful tool in their hands to help them reflect on the embodied roots of the language they are using. For me, learning Chinese also seems potentially to be a helpful practice in freeing up my remaining tendencies to implicitly think of language as having solely representational meaning (as well as other integrating effects, such as leading me to re-examine my beliefs). But in terms of my proficiency in Chinese, I have a very long way to go indeed. This is merely the first report of an intrigued learner!

Picture: Students learning in a mountain village in Xijiang, China, by Thomas Galvez CCSA 2.0

Table of pictograms and individual characters from Wikimedia.