I’ve never been much of a craftsman. By that I don’t just mean that I haven’t developed much skill with my hands. I’m thinking more of the way that a craft requires its practitioners to adopt and work within a particular set of socially sanctioned standards. To learn how to work wood, make pots, or almost anything else requiring skill, you start off by largely subordinating yourself to the standards you are taught. Ideas about ‘good’ carpentry or pottery, and how to do it well, have been developed over time and passed down to form a tradition with attendant standards. Creativity in such a craft can only come after you’ve accepted those standards and worked within them. You are only then able to stretch them when you’ve fully internalised them and allowed them to format your very understanding of quality itself. This is what Alasdair MacIntyre, the moral philosopher, described as ‘goods in a practice’ – the realistic basis of moral virtue. We can only develop goodness deeply rooted in individual and social experience, he thought, through internalising the standards offered by one or more ‘practices’ – those could be crafts in the usual sense, or sports, or academic disciplines, or professional requirements, or arts, or anything with a social dimension in which there are shared standards – a ‘craft’ at least in a metaphorical sense.

Recently I have been reflecting on my own difficulties with this process. My personal problem, I think, has always been not the discipline of learning any ‘craft’ in this broad sense in itself, but rather the requirement to accept a particular set of constraining rules in order to do so. Hence, the history of my varied academic studies, the history of my attempts to learn foreign languages, my engagement with different subjects when teaching, my engagement with different religious groups, and the history of my relationship to philosophy: all betray what one could unkindly call dillettantism, or more kindly a determined free-spiritedness: an inability to settle into one set of constraints and make the best of them. Perhaps the furthest I’ve got with any ‘craft’, with the support of a teacher in relatively recent times, has been with classical piano playing. I have at least pursued this for most of my life and got a great deal out of it: but I scraped through my grade 8 piano exam, and to this day am pretty hopeless at any kind of musical theory, scales or even basic key recognition. I’ve got myself through the threat implied by classical music’s standards by scorning many of them.

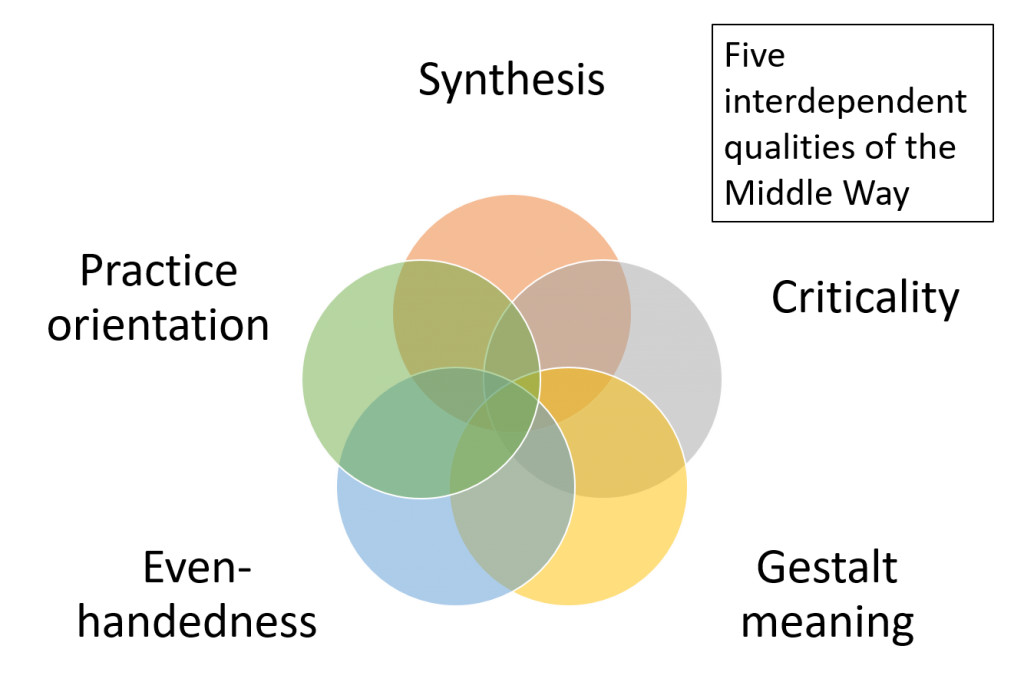

This tendency has both a positive and a negative aspect to it. The positive side is that it’s been a key condition of my development of Middle Way Philosophy. What’s distinctive about that approach is its synthetic nature – namely the way it brings different kinds of ideas and standards from different sources together for practical ends. I would never have created so much synthetic material if I hadn’t been so impatient with the constraints of any one craft. The drawback of it, though, can be a limitation of the depth of my engagement with any one given area of experience. Sometimes I yearn to be the master of a craft, with the capacity to learn more fully from others that it implies.

What’s particularly made me think about this once more is that I’m currently trying once again to engage with a craft – this time the craft of EFL (English as a foreign language) teaching. I did a basic certificate in this a long time ago, and also have lots of experience of teaching five other subjects (there’s the dilettantism again!), but I’m currently enrolled on a Diploma Course to learn how to do it properly – and preferably also make myself more employable. Like the other teacher training courses that I’ve done (and scraped through) in the past, it’s a challenge. Not intellectually, but because I have to take someone else’s set of apparently unreasonable, arbitrary standards, accept them, and work within them.

I started off in my first observed lesson with Henry V. I had been watching Shakespeare’s Henry V, and thought that the story of Henry V’s invasion of France and the Battle of Agincourt might interest the students. There was lots of vocabulary about combat that might have been of some use to them, because it was used metaphorically in everyday life. So I showed them a video about Henry V, and helped them to draw some combat vocabulary out of it. But was this directed sufficiently towards the needs of the learners? No. Were its aims and objectives clearly focused on their needs? No. Did I teach a manageable and helpful amount of vocabulary, properly contextualised in the way the students could use it? No. In the terms of the diploma, this was a disastrous lesson. Despite a great deal of more general teaching experience, I had nowhere near internalised the kinds of standards that were needed for the performance of the craft.

The key to meeting this challenge seems to be provisionality. I have to remind myself that these standards are a means to an end in a particular context, and that others understand the practical workings of that context far better than I do. The temptation for me is to reject them because they are too constraining – but that would be to repeat previous mistakes. I hope, and believe, that although I’m now in my fifties, I’m not too old to learn this. We’ll have to see how I get on with the rest of the course.

Of course, I do still think that learning one craft is not enough, if the effect is that one then gets stuck in the limiting assumptions of that craft. I still see philosophy as a pursuit that can only gain a helpful identity by being seen as beyond any craft – drawing on many crafts but not being subject to any of them. When I was studying for my Ph.D. in Philosophy, I met another student with a radically different attitude to mine. He described his Philosophy thesis as his “apprenticeship piece”, and was only too willing to embrace the arbitrary constraints of the particular sort of philosophy he was being supervised in. I wondered why on earth he was studying philosophy. Why not be a woodworker? Or at least a teacher?

But it’s likely that we can only get beyond craft, and into philosophy – or perhaps art – by growing up into a particular practice at least to some degree, before we learn to understand different practices in relation to each other. That’s what developmental psychologist Robert Kegan described as stage 4 thinking, where most educated and/or professional adults are to be found. The challenge seems to be not just to aspire to stage 5 thinking, beyond the craft, but also to understand when to embrace stage 4 in a provisional but still practically committed fashion.