It’s just over a year since we decided to live in France, my wife and I. We hadn’t planned to when we bought the house, but having moved in we decided to stay, instead of using it just for holidays. The decision sort of made itself. Perhaps the journeys back and forth were too exhausting, and there were other reasonable justifications we both agreed on.

We haven’t regretted it so far, although there have been challenges for us both; some we saw coming, some we didn’t, but none were overwhelming and most gave us sense of achievement as we tackled them together. I’ve taken up new pursuits and my wife is enjoying a much-deserved freedom from the tyranny of round-the-clock shifts as a hospital nurse in a collapsing NHS.

But I’ve been challenged by not being able to speak or understand anything other than simple French. I learned French at school over sixty years ago and learned it well, without ever being required to speak a word or listen to native speaker. I read 19th century French literature (Moliere’s ‘Le Misanthrope’) and more – at that time – modern novels (Alain Fournier’s “Le Grand Meaulnes” – a kind of French ‘Catcher in the Rye’): about three stuttering pages per 40 minute lesson. Yet though I passed my written exams well enough, I could hardly utter or understand a spoken word.

So since arriving here I’ve had to start the linguistic journey again from scratch, and from a different starting point: person-to-person communication. One of my first efforts at making sense was in a local shop selling electrical items. I had practised asking (in French) “Do you sell the things that allow a British plug to be inserted into a French socket?” In the shop, the meaning was somehow totally derailed, either because I’d used the wrong word for plug, or socket, or allowed, or inserted; or all of them; or because my accent was unintelligible; or because I was awkward and self-conscious; or because I’d neglected to say the customary polite “Bonjour” on entering the shop. I left without an adaptor, the shop assistant indicated somehow that they hadn’t got what she thought I wanted, and my feelings of hurt pride were soothed by her saying in English (and looking) “Sorry” , as I left.

Listening to spoken French is even more of a struggle. We have a next door neighbour whom we met when we first went to look over the house and its untended overgrown jungle of a garden. The estate agent had told him I spoke good French, and he followed us round keeping up a running commentary in almost unintelligible Norman dialect, from which I managed to catch an occasional familiar word, but hardly any sense whatever. But his friendliness was infectious and, on parting, I felt in fine good humour and was able to thank him for his kind welcome which, I stammered in schoolboy French, had “touched our hearts”.

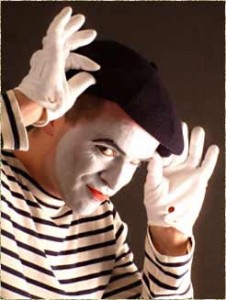

Reflecting on this later, I felt I had perhaps over-done the emotional loading in delivering this phrase in an unfamiliar language to a stranger. The whole experience felt surreal, as I had no idea if he had understood what I said, or what impression it had made on him. I felt uncomfortably ‘disarmed’. It’s no co-incidence that, in using that particular word, I admit to having lost my ‘weapon’, language, or ‘weapons’, there being many others at my disposal. On further reflection, it dawned on me that I always speak to impress or, as that is too much of a generalisation, attempting to impress is often a feature of what I say (and write). What impression am I trying to create in others? It’s a daunting question, and so important to me that I get to the bottom if it, that I shan’t try to answer it here, maybe another time.

The surreal quality of living in France where I have a very diminished capacity for communicating using the comfortable conversational language of everyday life, the ‘vernacular’, has gradually faded, but is still around. For one thing, now my ear is a little better attuned to French voices, and I’ve started to notice that, as far as my understanding goes, everyday French is much more straightforward and simply constructed than the French I learned at school. People talk about the weather (I thought this was just a particularly English trait), and exchange ‘small talk’ (some of which escapes my understanding), involving nods, smiles, sighs, tuts, sympathetic shrugs and head shakes of the familiar “Oh dear!” kind.

All this might seem blindingly obvious, but to me it’s a revelation, and it’s almost as if I’m learning how to communicate with my fellows from scratch. For one thing, I’m having to give thought to what I want to say before I open my mouth. Time and again, I realise that my default position is to impress, instead of to communicate a need or to respond to someone else’s. This just doesn’t work. If, as I suspect, I am trying to impress the other with my presumed superiority, communication becomes a battle of strength: either I prevail and ‘conquer’, or I submit and ‘grovel’. Sometimes, I think, I do both!

So, I’m learning, communication seems to work much better from a position of parity of esteem, not a battle of wills. So far, so (provisionally) good as a working theory and as a daily practice……..(more to follow on this)