Meditation is simple, but not easy. As proponents of the Middle Way we recognise that meditation is a valuable practice: it helps us to avoid delusion by making us almost instantly aware of our own relative lack of integration, and it can help us to make incremental progress with the process of integrating conflicting desires. So, we have a simple, valuable practice which we believe will be of benefit but one that is also not at all easy to do, and one that is not at all easy for many meditators to establish.

Setting the scene

This whole article is based on the assumption that it is better to meditate, than not. And if one meditates, I assume that a frequent, regular practice is better than irregular. The only justification I’m going to give has already occurred in the paragraph above! I’m also going to assume that the reader aspires to establish a regular meditation practice, but has not quite got there yet. This is a fairly common situation, as I understand it, and this is no surprise when you consider that meditation is usually a process of continually failing. We’re not well conditioned to being confronted with this!

There are plenty of articles out there on the internet that provide instructions on (for example) ‘How to establish effective habits’ and I don’t intend to replicate them here. Instead I’m going to work with an analogy from my own personal experience and explore the connections between establishing an exercise regime and establishing a meditation practice.

It was only a few years ago that I established a regular, daily meditation practice, and I’ve maintained it ever since with only the occasional day off. I know I’ve got the determination and self-discipline to do something like that if I think it is worth pursuing, and I still think it is worth pursuing now – that’s why I’m keeping it up. However, trying to give helpful advice in this context is a bit like the adults who, in my church-going youth, told us teenagers to refrain from sex until we were married: easy for them to say, they were invariably already married! So, I’m going to use the example of something that I’m still working to establish, and that’s a regular running regime.

It was only a few years ago that I established a regular, daily meditation practice, and I’ve maintained it ever since with only the occasional day off. I know I’ve got the determination and self-discipline to do something like that if I think it is worth pursuing, and I still think it is worth pursuing now – that’s why I’m keeping it up. However, trying to give helpful advice in this context is a bit like the adults who, in my church-going youth, told us teenagers to refrain from sex until we were married: easy for them to say, they were invariably already married! So, I’m going to use the example of something that I’m still working to establish, and that’s a regular running regime.

A running commentary

Over the years I’ve obviously run – there were the enforced running activities in PE and games lessons at school. Later on, when the running was not mandatory, it did not happen particularly often. I used to cycle to get from A to B, and that seemed like sufficient exercise – I’m talking about the kind of exercise that gets your heart rate up, that strengthens your cardiovascular system. After gaining some weight during my undergraduate years at university, the influence of my more active postgraduate peers led to me exercising regularly at the university gym – and although I concentrated on lifting weights, I also felt obliged to mix that with some running, mainly using treadmills. It was not rewarding, although I did get fitter (and thinner) – but as soon as I started full-time teaching that also stopped. There were other demands on my time and I didn’t prioritise running (or any other kind of cardiovascular exercise) as it was inconvenient and painful.

In my early 30s, when my wife was pregnant with our son, I was rather stressed and had borderline high blood pressure – exercise was recommended by the medical professionals. I tried a few things, none of them stuck. In time my blood pressure went down and the pressure I felt to exercise also declined. Which brings me to the end of my 30s, roughly this time last year, when I had arrived at a point where I’d realised that there are all sorts of things one can do (or stop doing) to improve one’s well-being, and regular physical exercise was probably the final one that I was dodging.

I settled on running for its simplicity. It can be done anywhere, at any time, alone or with company, and requires minimal specialist equipment – and I already had suitable footwear. The financial implications were practically zero, which helped. The technique, too, is simple: left, right, left, right, etc. I’m sure you know: it’s a bit like walking, but faster. My body was already reasonably well-prepared for it: I’ve never been slimmer, my knees were still in good working order and I was otherwise in good health. Just not at all fit.

I settled on running for its simplicity. It can be done anywhere, at any time, alone or with company, and requires minimal specialist equipment – and I already had suitable footwear. The financial implications were practically zero, which helped. The technique, too, is simple: left, right, left, right, etc. I’m sure you know: it’s a bit like walking, but faster. My body was already reasonably well-prepared for it: I’ve never been slimmer, my knees were still in good working order and I was otherwise in good health. Just not at all fit.

Now, just over a year later, I run regularly but not frequently – at least once a week. I am able to run at least 10 km without stopping, in less than an hour. I have no idea if that’s “good”, but it’s where I’m currently at. I haven’t injured myself, and I’ve kept it up through all the (admittedly mild) seasons, and I want to continue. I don’t do it for company, as I run alone, and I don’t do it to win, as I’ve never entered any kind of race. So how over the past year have I gone from basically no fitness to this, and what has it got to do with meditation? Read on through the following six points…

1. Just do it, and really do it

I did a lot of thinking about running. Not much talking, but a fair bit of listening. I pondered the best time, place, clothing, technique and so on. But you’re not actually running unless you’re actually putting one leg in front of the other, and probably working up a sweat at the same time. In the analogy that I’m making, meditation is much the same.

I did a lot of thinking about running. Not much talking, but a fair bit of listening. I pondered the best time, place, clothing, technique and so on. But you’re not actually running unless you’re actually putting one leg in front of the other, and probably working up a sweat at the same time. In the analogy that I’m making, meditation is much the same.

There is a lot of advice out there, probably too much. As many different opinions and options as there are people offering those opinions and options. But at some point you’re going to have to sit down (or lie down, or stand, or walk) and meditate. So do it, pick something simple and go with it, and don’t dress it up with a lot of unnecessary accessories.

2. Be conscious of self-consciousness

Maybe this is something that is more of an issue for me than it is for others, but at first I felt very self-conscious about being seen to go running. I didn’t see myself as ‘a runner’, and I had pretty much no experience of running. What if I was doing it wrong? I found a way around this – simply by going running at 6am on Sundays, when I was pretty much the only person out on the streets. It also helped that it was dark in the autumn and winter when I was getting established.

You may find the same thing with meditation – I certainly did. It helped me when I was starting to meditate to do it at a time when I knew that I wouldn’t be interrupted – so first thing in the morning, before my son had woken up. It also helped to have a friendly guide who you won’t feel ‘judged’ by – for me it was impersonal guided meditations via my phone, but for you it might be a meditation teacher in person. In time the feeling that I had to look and act like ‘a meditator’ has faded away.

3. Establish a regular time

I’ve already mentioned that I found a time that worked for me, both for running and for meditating. And for both it was first thing in the morning. Of course, this may be different for you, but don’t fool yourself with ideas like ‘But I’m not a morning person’. You might surprise yourself. There was a time that I thought I would simply die if I did not immediately eat breakfast when I woke up. Turns out that’s not true, but I only found out by actually doing it! The main thing is that you have a time when, in the usual routine, it is time to meditate: it is much easier to make it a (virtuous) habit then.

In terms of duration, I’ve always used a timer. When I started running I’d take a timepiece with me, as I’d have alternate between running and walking and without a timer I’d end up walking for a long time and running for only a short time. Now that I can run without stopping I leave the smartphone at home, but afterwards I record in my diary how far I ran and how long it took me (roughly). It appeals to the part of me that likes data, and provides a more objective way of tracking what I’ve done. As for how long, I’d just run until I felt that I really couldn’t run any further.

With the meditation practice, as I said I started with guided meditations so they were of a fixed duration. I don’t often use guided meditations now, but I do use a timer. Mainly because sometimes there are time constraints (for example, I’ve got to get to work on time). If there aren’t any constraints, then I meditate until I feel like I can’t meditate any more. I still have a timer running when I meditate, in fact I use the ‘Insight timer’ app on my phone. I don’t meditate for points (or to ‘win’ at meditating) but there is something satisfying about having it tell me that I’ve meditated for 222 consecutive days (or whatever).

With the meditation practice, as I said I started with guided meditations so they were of a fixed duration. I don’t often use guided meditations now, but I do use a timer. Mainly because sometimes there are time constraints (for example, I’ve got to get to work on time). If there aren’t any constraints, then I meditate until I feel like I can’t meditate any more. I still have a timer running when I meditate, in fact I use the ‘Insight timer’ app on my phone. I don’t meditate for points (or to ‘win’ at meditating) but there is something satisfying about having it tell me that I’ve meditated for 222 consecutive days (or whatever).

4. Establish a regular place

The analogy here is a bit weaker, but it still broadly works. There are various constraints on the routes that I run – they usually need to start and end at my house, they need to be suitably challenging (right amount of uphill and downhill), the fewer roads I have to cross the better, sometimes there needs to be the option to quit part way through. The main thing is that I have favoured routes which I tend to stick to, but I don’t always run the exact same route in the exact same direction. Variety, here, being the spice not the main ingredient.

In my analogy, the running route becomes the meditation location. It has to be convenient and conducive to the meditation you’re doing; you don’t want to be easily interrupted, but you’ve got to accept that there will be times when you can’t meditate in your preferred spot. My preferred location varies to fit the circumstances, but it helps to have a place that is ‘where I meditate’. In the winter I usually roll out of bed (in the dark) and sit next to my bed. In the spring and autumn, when it is lighter and warmer, I get up and go downstairs and sit by the patio doors. If it is summer I sit just outside on the decking. But there are times when I mix it up: for example, I might put on gloves and a hat and sit outside in the garden in the winter.

5. When things don’t go to plan…

5. When things don’t go to plan…

When establishing the running I had a regular time, regular routes, etc. but of course things don’t always go to plan. There were times when, for example, I’d be ill on a Sunday morning and not capable of getting out of bed, let alone running 5 km. Or maybe I’d be OK, but my son was ill and needed more attention than normal. Or I’d run a few miles then feel the need to urgently visit the toilet when the only real option was to run back home again. These are the occasions to be open to the idea of being flexible, of not being too rigid. A few weeks ago I had a huge headache on Sunday morning, but it had gone by the evening and so I ran instead in the evening. This might sound obvious, but it needs saying: it is so easy to say ‘Well, my habit is to run on Sunday morning and if I can’t run on Sunday morning then I won’t run at all’.

Astute readers will have noticed that there will be a clash in my schedule on Sunday mornings, as my habitual meditation time coincides with my habitual running time. Do I, perhaps, see the running as a meditation, to put one foot in front of the other and to really feel myself placing and lifting my feet, to follow the deep inhalations and exhalations from my diaphragm? Or do I just meditate first and then go out and run. Or maybe I run for a while, sit down to meditate on a park bench, then run back home again. I’ll leave that as something for you to ponder.

6. You’re not alone

My running is a solitary activity. I have always done it alone. But have I really? I sometimes talk to friends who also run about their running: why they do it, how they do it and so on. When I’m out running, even when it’s before 7am on a Sunday, I pass other runners: some wave, some give a dignified nod, with some it is just a knowing look. But there’s a kind of community in that – especially when you start to recognise them week after week.

You will probably get stuck with your meditation. At the point where I got stuck I was pretty much going it alone. However, through some connections that I’d made with more experienced meditators (via the internet) I was able to get un-stuck. They didn’t remove the blockage for me, but by discussing their own experiences and how they found a way through I was able to do the same thing myself, in time. I’ve also been able to return since to the things that were causing me to get stuck, and they now look very different to me. What was a source of frustration in my meditation has become something more helpful.

You will probably get stuck with your meditation. At the point where I got stuck I was pretty much going it alone. However, through some connections that I’d made with more experienced meditators (via the internet) I was able to get un-stuck. They didn’t remove the blockage for me, but by discussing their own experiences and how they found a way through I was able to do the same thing myself, in time. I’ve also been able to return since to the things that were causing me to get stuck, and they now look very different to me. What was a source of frustration in my meditation has become something more helpful.

This probably depends a great deal on your personal preferences, but it may be that you’ll find it easier to meditate regularly if you are involved with other meditators. It might be someone more experienced who can offer guidance, or it might be someone similarly inexperienced who is willing to muddle through with you, and to share encouragement. My wife has been meditating for significantly longer than I have. We often sit together in the evenings. It really is quite a different experience to sitting in meditation on my own, and it means that sometimes when I don’t feel like meditating there is encouragement from her to take a break from whatever else I’m doing and join in.

In terms of being part of a larger group – I’ve never done that with running, but I have friends who keep up a regular running practice mainly because they ‘have to’ as part of a group they’ve joined. Similarly, I wasn’t part of a meditation group when I was establishing a regular practice, but for others I know that is their way of reminding themselves of their intention to regularly meditate. I’ve already mentioned the Insight timer app – this also has a social side, in that it can show you other people using the app, all over the world, connecting you to a rather loose community of meditators. My feelings about this vary, but generally I see it as being akin to my very low-key interactions with the other runners that I meet when I’m running alone.

In terms of being part of a larger group – I’ve never done that with running, but I have friends who keep up a regular running practice mainly because they ‘have to’ as part of a group they’ve joined. Similarly, I wasn’t part of a meditation group when I was establishing a regular practice, but for others I know that is their way of reminding themselves of their intention to regularly meditate. I’ve already mentioned the Insight timer app – this also has a social side, in that it can show you other people using the app, all over the world, connecting you to a rather loose community of meditators. My feelings about this vary, but generally I see it as being akin to my very low-key interactions with the other runners that I meet when I’m running alone.

In conclusion

The point in all this is that establishing a regular practice of anything is going to take some effort, and there are things you can do to try and make the establishment more successful. I can offer various points from my own personal perspective, which might be broadly helpful but they probably aren’t going to be a perfect fit to your own personal situation. So what I’m recommending is to draw on your own experience. The things I’d encountered whilst establishing a regular meditation practice, in particular the things I’d learned about my own inclinations and preferences, could be applied to new virtuous habits that I’m trying to establish, hopefully making the process much easier.

If you’re trying to establish a regular meditation practice then I won’t wish you good luck – I don’t even know what that really means, other than wishing you well in your venture. Instead I will conclude by giving you this encouragement in the style of one of history’s most famous meditators (The Buddha):

If you’re trying to establish a regular meditation practice then I won’t wish you good luck – I don’t even know what that really means, other than wishing you well in your venture. Instead I will conclude by giving you this encouragement in the style of one of history’s most famous meditators (The Buddha):

“Such is a regular meditation practice. It can be established. It has been established.”

Follow this link to read my previous meditation blog post: Meditation 16: Conscious listening.

Index of previous meditation blogs

Photo credits

- Photo of runner on a forest track by Jenny Hill on Unsplash

- Photo of feet on steps by Bruno Nascimento on Unsplash

- Photo of Nike shoe by Kristian Olsen on Unsplash

- Photo of HTC phone screen showing Insight timer app by Jim Champion (own work)

- Photo of runner with hands on her head by Emma Simpson on Unsplash

- Photo of runners on the bridge by Curtis MacNewton on Unsplash

- Photo of seated man by Ian Keefe on Unsplash

- Photo of Buddha image by Igor Ovsyannykov on Unsplash

My prejudice against the so-called water-efficient toilets was seeded about two years ago when we moved from a one-lavatory house to a three-lavatory house – yes, that meant one lavatory per occupant. The big surprise on moving in was that the small outhouse on the back of the building contained a functioning old-style high-cistern pull-chain siphon-flush toilet, with panoramic views of the garden. This WC remains a little-used curiosity, and the outhouse is mainly used for storage now (or for posing in – see the photo on the right).

My prejudice against the so-called water-efficient toilets was seeded about two years ago when we moved from a one-lavatory house to a three-lavatory house – yes, that meant one lavatory per occupant. The big surprise on moving in was that the small outhouse on the back of the building contained a functioning old-style high-cistern pull-chain siphon-flush toilet, with panoramic views of the garden. This WC remains a little-used curiosity, and the outhouse is mainly used for storage now (or for posing in – see the photo on the right). That wasn’t the end of it though. When we moved in we were told by the letting agent that the house was not on a water meter – ‘Great!‘ I thought, ‘it won’t cost us if the toilets keep leaking‘. That turned out to be wrong, a letter arrived from the water company telling us that we did in fact have a water meter. Not long after that the flush mechanism in the upstairs toilet malfunctioned and I replaced it. A few months later the dripping began again and, much more quickly this time, I ordered the new washers and sorted it out. And this pattern has repeated, the toilets requiring regular minor maintenance leaving me wondering if I could bulk-order the replacement washers (see the photo on the right).

That wasn’t the end of it though. When we moved in we were told by the letting agent that the house was not on a water meter – ‘Great!‘ I thought, ‘it won’t cost us if the toilets keep leaking‘. That turned out to be wrong, a letter arrived from the water company telling us that we did in fact have a water meter. Not long after that the flush mechanism in the upstairs toilet malfunctioned and I replaced it. A few months later the dripping began again and, much more quickly this time, I ordered the new washers and sorted it out. And this pattern has repeated, the toilets requiring regular minor maintenance leaving me wondering if I could bulk-order the replacement washers (see the photo on the right). In order to achieve variable-volume flushing the designers of modern ‘dual flush’ toilets have done away with the cistern-emptying siphon mechanism. Instead, in the common ‘drop valve’ design, when the flush buttons are pressed a plug is yanked out of a plughole in the bottom of the cistern and the water drains down into the toilet bowl. One of the flush buttons yanks the plug a long way out of the plug hole, so that the entire cistern drains before it falls back in to seal it up again. However, the other flush button only yanks the plug out a little way, and it drops back in when only a fraction of the water in the cistern has escaped.

In order to achieve variable-volume flushing the designers of modern ‘dual flush’ toilets have done away with the cistern-emptying siphon mechanism. Instead, in the common ‘drop valve’ design, when the flush buttons are pressed a plug is yanked out of a plughole in the bottom of the cistern and the water drains down into the toilet bowl. One of the flush buttons yanks the plug a long way out of the plug hole, so that the entire cistern drains before it falls back in to seal it up again. However, the other flush button only yanks the plug out a little way, and it drops back in when only a fraction of the water in the cistern has escaped. So 16 years later, and the traditional siphon flush lavatory is an endangered beast. The dual-flush design is now far more popular, having been the installation of choice in new-builds since 2001. This is a long enough time for the drawbacks of this new technology to become apparent, and for not-for-profit bodies like Waterwise to investigate and report on the false economy of switching from siphon flushers to valve mechanisms. It makes for a satisfyingly ironic headline in the news: “So-called water-efficient toilets leak millions of litres every day”, but perhaps it is better seen as a cautionary tale about the unintended consequences of introducing what seemed like common-sense changes.

So 16 years later, and the traditional siphon flush lavatory is an endangered beast. The dual-flush design is now far more popular, having been the installation of choice in new-builds since 2001. This is a long enough time for the drawbacks of this new technology to become apparent, and for not-for-profit bodies like Waterwise to investigate and report on the false economy of switching from siphon flushers to valve mechanisms. It makes for a satisfyingly ironic headline in the news: “So-called water-efficient toilets leak millions of litres every day”, but perhaps it is better seen as a cautionary tale about the unintended consequences of introducing what seemed like common-sense changes. There are cultural factors at play here too, ones that are often difficult for us to appreciate because they are part of our own conditioning. One very simple innovation that greatly improves water-efficiency is the urinal, especially the waterless variety. However, when was the last time that you saw a urinal in a domestic setting? And, ladies, when was the last time you saw an (appropriately designed) urinal in a public lavatory? There are not really any material barriers to installing urinals in homes, or to widespread installation of female urinals in public toilets, so what’s stopping us? With the increased technology surrounding the business of urinating and defecating the subject has become closer to taboo in society – I don’t know how exaggerated the reports are, but consider the technological lengths employed in urban Japan to cover up the embarrassment that comes with the fact that humans need to urinate (musical toilets and so on).

There are cultural factors at play here too, ones that are often difficult for us to appreciate because they are part of our own conditioning. One very simple innovation that greatly improves water-efficiency is the urinal, especially the waterless variety. However, when was the last time that you saw a urinal in a domestic setting? And, ladies, when was the last time you saw an (appropriately designed) urinal in a public lavatory? There are not really any material barriers to installing urinals in homes, or to widespread installation of female urinals in public toilets, so what’s stopping us? With the increased technology surrounding the business of urinating and defecating the subject has become closer to taboo in society – I don’t know how exaggerated the reports are, but consider the technological lengths employed in urban Japan to cover up the embarrassment that comes with the fact that humans need to urinate (musical toilets and so on).

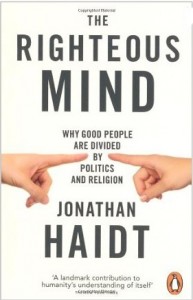

One of the most prominent researchers in this area is Jonathan Haidt, and in his 2012 book The Righteous Mind he sums it up like this:

One of the most prominent researchers in this area is Jonathan Haidt, and in his 2012 book The Righteous Mind he sums it up like this: In the subtitle above I imply that I possess the metaphorical elephant, whereas – in the light of Haidt’s moral psychology model – it might be more accurate to say that the elephant both is me (as the part of my mind that works before and at a more fundamental level than my conscious cognition) and has me (in the sense that the conscious cognitive “I” serves it and has little control over where the elephant is going).

In the subtitle above I imply that I possess the metaphorical elephant, whereas – in the light of Haidt’s moral psychology model – it might be more accurate to say that the elephant both is me (as the part of my mind that works before and at a more fundamental level than my conscious cognition) and has me (in the sense that the conscious cognitive “I” serves it and has little control over where the elephant is going). Looking back on it, perhaps there was a bit of embarrassment that I didn’t have a rational reason for not wanting to eat eggs any more, after all, usually people want to know why you’ve changed your position on an issue and it seems culturally appropriate to have a ‘proper’ rational reason. My wife said something like “If that’s your decision that I stand by you making it.” and I went off to make something eggless for our evening meal. The elephant had decided: “Boom! No more eggs for you!” and then my cognitive mind was left floundering around trying to do some strategic reasoning that would no doubt be required in socially justifying my new food ethos.

Looking back on it, perhaps there was a bit of embarrassment that I didn’t have a rational reason for not wanting to eat eggs any more, after all, usually people want to know why you’ve changed your position on an issue and it seems culturally appropriate to have a ‘proper’ rational reason. My wife said something like “If that’s your decision that I stand by you making it.” and I went off to make something eggless for our evening meal. The elephant had decided: “Boom! No more eggs for you!” and then my cognitive mind was left floundering around trying to do some strategic reasoning that would no doubt be required in socially justifying my new food ethos. It goes back, of course, to childhood. I was a fantastically fussy eater, ‘difficult’ about food, and I cannot remember ever not being this way. My brother, two years younger, was quite different: a human dustbin, he’d happily eat what I would not, and probably this was why so many adults asked if we were twins; despite him being two years younger he was always the same size as me (as you can see in the photo on the right, taken perhaps when I was 9 and he was 7).

It goes back, of course, to childhood. I was a fantastically fussy eater, ‘difficult’ about food, and I cannot remember ever not being this way. My brother, two years younger, was quite different: a human dustbin, he’d happily eat what I would not, and probably this was why so many adults asked if we were twins; despite him being two years younger he was always the same size as me (as you can see in the photo on the right, taken perhaps when I was 9 and he was 7). What was the ‘right’ choice for us to make? To what extent would he decide what he ate and why? Either the elephant, or pragmatism, made the decision: we weren’t going to specially buy in meat for him to eat at home. He grew up healthy and un-deformed, despite some frowning from meat-eating adults, and he eventually settled into something like a pescatarian diet—vegetarian, but with occasional fish dishes—and, as far as I know, he’s never eaten the conventional chicken, beef, turkey, lamb and pork foods that most of his friends eat.

What was the ‘right’ choice for us to make? To what extent would he decide what he ate and why? Either the elephant, or pragmatism, made the decision: we weren’t going to specially buy in meat for him to eat at home. He grew up healthy and un-deformed, despite some frowning from meat-eating adults, and he eventually settled into something like a pescatarian diet—vegetarian, but with occasional fish dishes—and, as far as I know, he’s never eaten the conventional chicken, beef, turkey, lamb and pork foods that most of his friends eat.

It’s been 40 years since I was born, and I reckon I do not fall within Rohr’s grouping of people “formed in the last 30 years”. Not due to the mathematical exactness of his figures (in context he did not literally mean a cut-off at 30 years old!), but due to the fact that I was brought up in a very rigid – and ordered – container. My family was of the more evangelical protestant Christian variety and our acts of worship were not confined to Sundays (although there was a service every Sunday, sometimes two), but spread to other activities throughout the week and a general feeling of being watched at all times by an omniscient God who was, by turns, strict and loving. This religious context defined the pattern of my weeks and years, much more so than any other aspect of my life such as school or neighbourhood friendships. To put it into Rohr’s terms, I was, quite definitely, born into a box of order.

It’s been 40 years since I was born, and I reckon I do not fall within Rohr’s grouping of people “formed in the last 30 years”. Not due to the mathematical exactness of his figures (in context he did not literally mean a cut-off at 30 years old!), but due to the fact that I was brought up in a very rigid – and ordered – container. My family was of the more evangelical protestant Christian variety and our acts of worship were not confined to Sundays (although there was a service every Sunday, sometimes two), but spread to other activities throughout the week and a general feeling of being watched at all times by an omniscient God who was, by turns, strict and loving. This religious context defined the pattern of my weeks and years, much more so than any other aspect of my life such as school or neighbourhood friendships. To put it into Rohr’s terms, I was, quite definitely, born into a box of order. For example, I was indebted to the Jesus Christ whom – I was told – had died for my sins, but didn’t believe that anyone was listening when I prayed. I respected by parents, who became ministers in our denomination when I was 16, but had to find a way of hiding the fact that I was trying out drinking, smoking and other recreational drugs with my peers. I had been instilled with the ideal that sex was expressly for marriage and marriage was for life, but everyone else seemed to be doing it and when I eventually started doing it too it didn’t seem at all immoral or wrong – nothing had ever seemed so natural, normal and right. In other areas, in my school education for example, I was realising that there were well-justified reasons for believing that the universe was not centred around the human race, and this contradicted the interpretation of holy book that I’d been brought up to revere.

For example, I was indebted to the Jesus Christ whom – I was told – had died for my sins, but didn’t believe that anyone was listening when I prayed. I respected by parents, who became ministers in our denomination when I was 16, but had to find a way of hiding the fact that I was trying out drinking, smoking and other recreational drugs with my peers. I had been instilled with the ideal that sex was expressly for marriage and marriage was for life, but everyone else seemed to be doing it and when I eventually started doing it too it didn’t seem at all immoral or wrong – nothing had ever seemed so natural, normal and right. In other areas, in my school education for example, I was realising that there were well-justified reasons for believing that the universe was not centred around the human race, and this contradicted the interpretation of holy book that I’d been brought up to revere. The thing about this transition is that I didn’t then enter the metaphorical reorder box, I just cobbled together a different order box: I was an atheist, a materialist, a natural realist, a scientist, a rationalist (and so on – follow

The thing about this transition is that I didn’t then enter the metaphorical reorder box, I just cobbled together a different order box: I was an atheist, a materialist, a natural realist, a scientist, a rationalist (and so on – follow