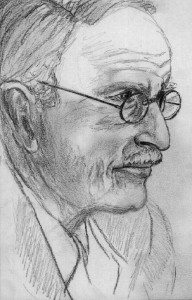

Carl Gustav Jung (1875-1961), the great Swiss psychoanalyst, had a long and rich life and left a huge body of writings behind him. I think he offers a huge contribution to our thinking on the Middle Way. Though his approach has been dismissed by some who regard themselves as hard scientists or analytic philosophers, I would argue that these criticisms are often based on prejudicial misunderstandings of his work and its significance. More than anything, I think his contribution is philosophical, in the sense of offering us new and helpful ways of understanding and assessing our beliefs and the ways we interpret our experience. He also offers a personal narrative of his incredibly rich and inspiring inner life. Questions remain about his effectiveness as a therapist – a point that I don’t feel in any position to assess – but even if he ‘cured’ nobody, his interactions with patients provided a strong basis of experience that supports the philosophical and cultural value of his work.

Jung was the son of a Protestant pastor, and qualified in medicine before specialising in psychiatry. He encountered and was influenced by Freud, the founder of psychoanalysis, but rejected some of Freud’s dogmatic assumptions, such as his materialism and his reduction of desire to sexuality. In this respect you could compare Jung’s position to that of other philosophical disciples who have learnt much from but greatly surpassed their masters (such as Plato and Aristotle), primarily by identifying dogmatic assumptions that were holding back their masters and freeing themselves of those assumptions.

Jung saw himself as a man of science, and constantly strove to meet the standards of objectivity that he felt were necessary to meet what he saw as the exacting standards of science. This is what led him to be so cautious during his lifetime in publishing accounts of his inner experience. This commitment seems to me double-edged: it led him towards a genuine objectivity of approach, but also led him to attempt what was probably impossible, to convince those committed to a naturalistic approach to science that phenomena as remote from publically-verifiable, reproducible proof as the unconscious or the archetypes should be taken seriously in scientific terms. In my view it is science that needs to try to live up to Jung’s high standards of objectivity, not the other way round. Jung was not afraid of the use of ‘private’ experience, or of material from cultural or religious traditions, and thus did not unnecessarily narrow the field of investigation, or impose likely conclusions that are the result of limitations in the methodology, in the way that those who insist on ‘hard’ scientific evidence have to do. His hypotheses about these areas of experience provide us with a valuable basis of understanding that is well supported by Jung’s experience, and by the provisionality that went with his scientific approach.

Jung’s biggest contribution to our understanding of the Middle Way has to be the concept of integration – which Jung more commonly referred to as individuation. Recognising that our experience comprises a variety of energies, symbols and beliefs that may be in conflict, with some repressing others and the repressed elements often unconscious, Jung saw the goal of human life as overcoming these conflicts and bringing these energies together. This insight has huge implications far beyond the medical model of psychotherapy – for example as the basis of moral objectivity – though this is a point that Jung himself only seems to recognise implicitly rather than advertise explicitly.

I prefer the term ‘integration’ to ‘individuation’, because this makes it clear that integration is not only the process of psychological development in an individual, but can also be applied at a social level. Again, I would say that Jung also recognised this point implicitly, but did not discuss it explicitly because of the extent to which exploring these philosophical implications might potentially threaten the scientific credentials he wanted to maintain. I see integration as the Middle Way inside out: rather than just avoiding dogmatic beliefs on either side, integration brings together experiential beliefs and energies that at first were unnecessarily opposed. Each supports the other, because it is only by avoiding metaphysical beliefs (that cannot be integrated) that we can make integration possible.

Jung’s other huge contribution to our understanding of the Middle Way lies in his development of the concept of archetypes. There has been much confusion about what Jung meant to assert about the status of archetypes, much of which has arisen from his use of the term ‘collective unconscious’ where he placed the archetypes. Some people have mistaken the collective unconscious for some kind of Platonic realm of absolutes, but Jung makes it clear that he is only referring to the universality that comes from genetic similarity between human beings, that gives us all similar psychic functions. These psychic functions need to be expressed by symbols, but the form of those symbols will differ between cultures. Thus, for example, the Shadow archetype is the one we encounter in symbols like Satan, Darth Vader, Sauron and Voldemort – an embodiment of evil found in all cultures because it reflects the psychic function of rejecting what we do not identify with. Any creature with aversions will have a Shadow of some kind, however it is expressed.

Archetypes are very important in understanding the Middle Way, because they allow us to distinguish between meaningful symbols that are found universally (because of their psychic function) and metaphysical ‘truths’. So, in the case of God, for example, the God archetype came first, and is meaningful to us because it represents a psychic function, regardless of whether or not we ‘believe’ in God. Belief or disbelief in God seems to me completely irrelevant to the meaning of the archetype. I think this is what Jung probably meant when he said that he did not believe in God, but that he ‘knew’ God, probably in the sense that he directly encountered God in experience.

After the Buddha, perhaps, I can’t think of any thinker whom I think is quite so rich and rewarding as a source of insights into the Middle Way as Jung. I am not really well-read in later Jungians that others recommend, such as James Hillman, so I must reserve judgement on their value. But whether you read more recent Jungians as well or not, I’d highly recommend going directly to the source. His autobiographical book ‘Memories, dreams, reflections’ is a very good place to start, because it gives you a big picture of Jung the man, and of his rich inner life, as well as of his scientific development.