Original

A man was on his way from Jerusalem down to Jericho when he was set upon by robbers, who stripped and beat him, and went off leaving him half dead. It so happened that a priest was going down by the same road, and when he saw him, he went past on the other side. So too a Levite came to the place, and when he saw him went past on the other side. But a Samaritan who was going that way came upon him, and when he saw him he was moved to pity. He went up and bandaged his wounds, bathing them with oil and wine. Then he lifted him on his own beast, brought him to an inn, and looked after him. Next day he produced two silver pieces and gave them to the innkeeper and said “Look after him; and if you spend more I will repay you on my way back.” (Luke 10: 30-35, Revised English Bible)

Variation 1

A drug addict was sheltering for the night in a car park under a block of flats, when he was set upon by muggers, beaten up and stripped of what few possessions he had. A business man living in the block, on his way to his car, passed close by the unconscious drug addict. However, the business man was preoccupied with thinking about a hostile bid that had been launched against his company by an asset-stripping corporation, and was intent on finding ways to foil the bid and save the jobs of his staff. He completely failed to notice the unconscious drug addict.

Variation 2

In the late evening on a side street in London, a homeless man was set upon by muggers, beaten up and stripped of what few possessions he had. A philosophical writer passed by, his mind full of the book he was writing, that he was sincerely convinced could change the world for the better by challenging fundamentally wrong thinking. The writer dimly glimpsed the homeless man across the street, but thought it likely that others would look after him, and did not want to be distracted from his train of thought.

Variation 3

Late at night in a dangerous area of downtown Karachi, gang warfare resulted in a shootout in which one gang pursued the other down a street, shooting. Three people from the losing gang were injured and lay at different points along quite a long street. The victorious gang just left them there and went off. There was no sign of the police or any medical attention for the injured people. A little later a local shopkeeper crept down the street. He was shaking with fear but had to get home. When he passed the first injured person, he thought it best to leave him alone, because he didn’t want to take the risk of getting involved with the gangs in any way. When he got to the second some way further down the street, he again made the same decision. However, his conscience then began troubling him, and he began to feel that it was his social and religious duty to help injured people, whoever they were. When he reached the third man lying injured, he changed his mind. His shop was now not far away, so the shopkeeper dragged the injured man to his shop, and, with the help of members of his family, began to give him first aid. Some hours later, he managed to get an ambulance to take the man to hospital.

Variation 4

In a back street in a rough neighbourhood of Chicago, a black man was seen lying on the ground, apparently with blood smeared all over him. A white Christian man, who had always believed in the example of the Good Samaritan and that it was right to help strangers in distress, came across him and was determined to help him. However, as soon as he came close, the black man sprang into action and his accomplices appeared from nearby hiding places. The white man was beaten up and robbed.

Variation 5

A promiscuous homosexual in a precarious state of mental heath, desperate for sex with someone, had been cruising from one gay bar to another but failed to find a partner for that night. Finally, on his way home, he found a man lying injured in a side street. The injured man was quite young and attractive, so the gay man took him home and bandaged up his wounds. The injured man was grateful, but was neither gay, nor in any state to be interested in consensual sex. The gay man then raped him, but afterwards took him to hospital for further attention as though nothing had happened.

Variation 6

A destitute young woman is attacked, raped and robbed in the back lane of a Mumbai slum. She lies there seriously injured and unconscious, and an older woman from a nearby shack goes out to help her. She mutters and curses as she brings the young woman into her house. This is just one more thing in a life of constant stress. Her husband is a drunkard, her teenage sons are drug addicts, she finds it hard enough to keep her family together when she receives no gratitude and much abuse from them. Nevertheless, she feels it is her duty to look after the young woman when she has been attacked, and she takes her in, bandaging her with strips of her own clothes, whilst complaining about the sacrifice she is making as she does so. When one of the older woman’s sons comes back to the shack early the following morning, he finds the injured young woman still lying there, and his mother hanging from a beam, having committed suicide.

Variation 7

A young Spanish woman is in a hurry to get to her office, in a street in Barcelona. She is afraid of losing her job if she is late, and has already been warned by the boss about her punctuality. Unemployment is very high amongst young people, and it will be very difficult for her to get a new job if she loses this one. She notices an injured man lying unconscious on the pavement, and nobody seems to be helping him. She gets out her mobile phone and rings the emergency services to inform them, but then hurries on.

Variation 8

A young man has a painful memory of a time when he was a teenager, and he tried to help his cousin who was choking. However, he did not know what to do to clear the obstruction, and actually made the situation worse. By the time help from others arrived, his cousin was dead. As a result the young man has resolved never to get involved with people who need help, and has an instinctive lack of confidence, believing implicitly that he will make things worse for them. Thus when he is driving along a remote highway and sees an injured man lying by the side of the road, he only half-consciously decides not to get involved and to simply pass by.

Variation 9

In the past a lorry driver used to pick up hitch hikers and talk to them. He quite enjoyed having some company on his long drives. However, recently he has been sternly told by his boss that he must not pick up any passengers, and that to do so will invalidate the firm’s insurance policy in the event of an accident. One day the lorry driver is passing along a remote moorland road, when he sees an injured man lying helpless and unconscious by the side of the road. He stops and looks down at the man and feels helpless as to how to start dealing with his extensive injuries. He takes out his mobile phone to call an ambulance, but there is no signal. He thinks of taking the man with him in his cab to the nearest hospital, but remembers his boss’s stern warning. So, with some regret he then leaves the injured man by the side of the road and goes on.

Variation 10

A man is attacked and robbed by outlaws in a remote place on a road in nineteenth century Australia. A poor man, an ex-convict, finds the injured man, takes him on his horse and takes him back to his own house, which is not too far off but is the only house for some distance. There he tries to help him, but the injured man soon dies of his injuries. A few days later, a sheriff comes to the house. Having heard about the robbery, he is trying to find out what happened to the victim. The ex-convict shows the sheriff the grave where he buried the victim, and explains truthfully what happened. However, because of his criminal past the sheriff does not believe him, and assumes him to be the robber. He is immediately arrested and imprisoned.

*****************************************************************************************

Moral plurality

A university researcher, in what became known as ‘The Good Samaritan experiments’, once set up a situation in which a man (actually an actor) was lying in a hallway apparently in need of help. A group of theology students were told to come to a certain venue in the university for a seminar where they would give a presentation about the parable of the Good Samaritan, but things were so set up that all these students would have to pass the ‘injured’ man in the hall. Only a minority of the students stopped to offer help, and the rates of help were lower in those who were late for the seminar.

Is this an example of the hypocrisy of ‘religious’ ethics? Actually I think we should think about this is a wider perspective, letting go of the framework of reactions to ‘religion’ that distorts people’s responses to it. It seems that the story of the Good Samaritan encapsulates for many people something about moral good – that we should feel and act upon our compassion for those who are suffering, and that we should follow the same kinds of expectations of care we might have in intimate relationships and extend them to wider society. However, this is overwhelmingly only a theoretical view, and not even the majority of those who have thought carefully about the story (if we are to believe the results of the experiment) value this more than the other values that they have developed over their lives as embodied beings. These would include the value of existing social duties and relationships (including the duty to turn up and give a presentation in a seminar on time), as well as perhaps the value of individual goals and aspirations.

People’s responses to the Good Samaritan story, then, often seem riddled with hypocrisy. A little while ago I saw a video posted on Facebook where a similarly needy-looking person was lying on a pavement in a crowded city street and calling for help. But the vast majority of people did not stop to offer any. What struck me most about this Facebook post was not so much the video itself but the comments, all of which attacked and blamed the people who had failed to stop. Yet all the indications seem to be that most of the people who commented in this way would not themselves have paused to stop. Most of us are like the priest or the Levite, not the Samaritan (and in that I’d realistically include myself, in many situations). What’s more we have lots of good reasons for not stopping: fear that the person apparently in need may be deceiving or take undue advantage of you, reluctance to drop other pressing actions that we value, and the fair likelihood that there will be other better-qualified people around to offer help instead (and indeed that we might just be in the way) are perhaps foremost amongst those reasons. To dismiss the people who do not stop as ‘uncaring’ and ‘selfish’ is both inaccurate and shows a very crude understanding of ethics.

So, there seems to be a big mismatch between people’s perceptions of the Good Samaritan as a moral ideal and the psychological context in which moral judgements are often made. I’d suggest that’s a good exemplification of the huge and unnecessary gap that is often found between ethics and psychology. People assume that ethics must involve conforming to some sort of absolute (and completely abstract) ideal, and then either fail to take it seriously in practice or feel unnecessarily guilty about not doing so. Then on the other hand, psychological observations, conventionally limiting themselves to a scientific mode that is assumed to exclude ‘values’, quite unnecessarily avoid drawing out the moral implications of their findings. I would argue, instead, that justifiable ethics need to combine a realistic understanding of our own processes, of the kind offered by psychology, with a degree of ‘stretch’ – that is, a challenge for us to face up to conditions just a little more than we might have done otherwise.

I wrote the ten variations on the Good Samaritan as a way of exploring some of the implications of that perspective. I don’t want for a moment to suggest that the original Good Samaritan is not good – he is. Presumably there was a chance that he could have followed the priest and the Levite in passing by on the other side of the road, but he didn’t. He must have had some of the necessary conditions there – for example a ready sympathy and a degree of courage – but he also chose to apply those qualities and to stretch himself in doing so. All that is very admirable. But there are a host of other people who could have similar, or quite different, responses, in similar circumstances, who are equally good, and who are also slightly stretching themselves. The variations are an attempt to explore what different forms goodness can take, and are thus an exercise in moral plurality.

Moral plurality must not be mistaken for relativism. It does not imply that any response is as good as any other response. What I mean by moral plurality is that there are many different ways of morally stretching oneself in different circumstances. There may, indeed, be a ‘best possible’ response in any given circumstance, but we are seldom in a position to know what that ‘best possible’ response is. Moral practice, instead, needs to face up to our degree of ignorance as well as our situatedness. There is moral plurality – that is, a variety of different good options – both from the wider viewpoint we are taking here when we compare different ‘Samaritan’ type stories, and perhaps even from the particular standpoint (given their degree of ignorance) of one of the characters in the stories. Nevertheless, wider judgements are better and more adequate than narrower ones.

In the different variations, I wanted to explore how different base conditions might make actions that we consider ‘bad’ in some respects nevertheless good – perhaps even the best in the circumstances.

In variation 1, the business man fails to notice the man in need of aid because he is preoccupied with saving his company. He has motives that we would probably regard as good in saving his company, but as an embodied being his capacity for attention is limited. Yes, he could have been more aware, but it may also be the case that saving his company was far more important than helping the drug addict.

In variation 2, the philosophical writer did not want to be distracted from his train of thought. He could have been seriously deluded there, and his train of thought probably wasn’t nearly as important as helping the homeless man. However, it is also possible that he was not deluded and that his train of thought really was extremely important. It is also possible that he was just offering a weak excuse to himself in thinking that others would look after him – but in a London street, there was probably also a good chance of that. The question is perhaps more how much of a delay there would be. So, the writer may have been acting badly, but he may also have been acting well. We need to recognise our degree of ignorance here before we heap blame on him based only on an unrealistic application of social conventions.

In variation 3, the shopkeeper helped the third man, even though he didn’t help the first two. Perhaps we could apply this to the priest and the Levite in the original story. Maybe they didn’t help the injured man in the story, but they helped someone else later. Obviously it is better to help one person, even if you leave the other two, than to help nobody. Are we really going to blame the shopkeeper too much for his limitations?

In variation 4, the white Christian has all the intentions of being a good Samaritan, but it turns out badly for him. To judge him harshly because the results were bad is obviously unfair – this is a matter of moral luck. He deserves praise for trying to help, even though the outcome is bad. Similarly, if he failed to be a ‘Good Samaritan’ in future due to this bad experience, we could hardly blame him. The racial element in this story is realistic in the context, but obviously should make no difference to our judgement.

I imagine that variation 5 may be the most controversial for many. Here the ‘Good Samaritan’ actually commits a violent crime against another in the course of being a Good Samaritan. His motives for helping another were very mixed, and obviously he deserves blame for rape (the gender of his victim making no difference). Nevertheless, I’d want to suggest, he deserves praise for the help he did give, and the mixed context should not stop us appreciating that. Instead of helping the injured man, he could have just raped him and left him in the street – but he did more than that.

In variation 6, the ‘Good Samaritan’ is so desperate and alienated that she is on the verge (it turns out) of taking her own life. Yet, even in this situation, she has a little space in her heart to help another. Given her degree of alienation, it is hardly surprising if she complains about it at the same time as helping the young woman, but nevertheless, her actions show a degree of openness in her judgements. She is perhaps the most praiseworthy of all the characters in these variations.

In variation 7, the young Spanish woman’s anxiety about her job stops her doing any more than merely phoning the emergency services. But that was a helpful thing to do, for which she deserves praise in the circumstances.

In variation 8, the young man is motivated by not wanting to make the situation worse. His worries about this are probably exaggerated and deluded, but nevertheless, we need to think realistically about what he could do given this condition. If he had stopped and overcome this anxiety, we might praise him even more, but we could hardly expect this given his psychological state.

In variation 9, the lorry driver really wants to help the injured man, and carefully considers how to act. Perhaps he is mistaken in his interpretation of the consequences of taking the injured man in his cab, and he is interpreting the rules of his company too legalistically. Nevertheless, he is reflecting, and sincerely trying to do the best thing. He deserves a fair amount of praise in my view, for trying to do the best thing in the circumstances.

Finally, in variation 10, as in variation 4, the Good Samaritan’s actions turn out worse for him – in this case both because of the mortal severity of the man’s injuries and because of the Samaritan’s criminal record and resulting social reputation. This can act as a reminder of how much of our socially-driven moral judgements are actually dependent on luck and subject to ignorance.

All of these ‘Good Samaritans’ are good to some degree – obviously some better than others – though some did not help the injured man at all, and others helped in ways that were loaded or compromised in other ways. If we want to help and encourage ‘Good Samaritans’ in the world, I would argue, we need a far more adequate understanding of the complexity of the moral context than is usually applied to such cases.

Other Middle Way parables: Achilles and the Tortoise, An Acre of Forest, The Lute Strings, The Ship, The Boredom of Heaven

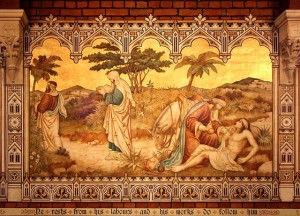

Picture by John Salmon (CC BY SA 2.0 – Wikimedia Commons) from All Saints Church, Bracknell

There’s hardly a variation amongst this extraordinarily imaginative collection that doesn’t light up some dark crevice of my own experience, in all its domains, including my nursing and chaplaincy work. That light is warm and encouraging about how I can make better judgements in challenging situations; and see the challenge to choicefulness in all situations, if I can see each experience with fresh eyes. I think (and hope) many others who read this parable and the commentaries on it will feel the same as I do.