Cycles are an easily identifiable feature of universal human experience. Arguments go ’round in circles’. Efforts to change get caught in vicious circles or Catch 22s. Buddhism has its Wheel of Samsara (or ‘Wheel of Life’), in which craving leads to frustration and then more craving. Various social sciences identify various cycles: the economic cycle, the political cycle, the cycle of addiction, the cycle of violence, the cycle of poverty and degradation, and so on. What do these cycles have in common? Are they inescapable?

One interpretation I want to resist from the start is the belief that these cycles are inescapable (or alternatively, only escapable through some miraculous supernatural cause) because ‘natural’. The cycles I’ve mentioned so far all depend on the human brain, so we have no reason to conflate them with other sorts of cycle that are entirely (rather than debatably) beyond human control – such as eco-cycles, planetary cycles, or the cycle of birth and death. Though they may share some formal features with other kinds of cycles, the kinds of cycles I want to focus on here are within the sphere of human judgement: and that’s a sphere in which the extent of our responsibility remains perpetually vague and unresolved.

What the cycles within that sphere seem to have in common is their relationship to looped synaptic tracks in the brain. Broadly, we can see our feedback loops as leading from the older ‘reptilian’ lower brain, where our basic motives arise, to the pre-frontal cortex in the front of our brains, where we conceptualise and contextualise in a more distinctively human fashion. But this understanding of the situation then gives rise to new motives, looping us back to the back of the brain. We ‘go round in circles’ when we are in the habit of following certain entrenched synaptic tracks, in which certain kinds of desires give rise to certain kinds of beliefs, that then reinforce the desires and again reinforce the beliefs. For example, Marc Lewis shows this process in the brain of an addict in his book The Biology of Desire, reviewed here. As Lewis points out, it’s not only drug addicts that go through such feedback loops, but to some extent all of us.

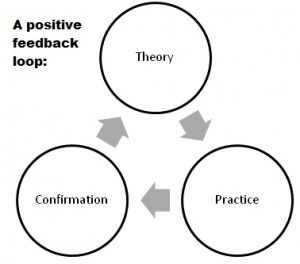

We also go through such cycles over a shorter period of time when we ‘ruminate’: going through a proliferating cycle of thoughts that are usually motivated by obsession or anxiety. If you keep thinking the same thoughts over and over again and can’t get to sleep, or can’t focus on work or meditation, you are probably caught in a positive feedback loop.

Positive feedback loops are the means by which we can set up good habits as well as bad ones, and as long as we are in a stable environment in which those habits are helpful, relying on them isn’t too much of a problem. However, if we want to be able to adapt to ever-changing new circumstances, we need to be able to move out of unhelpful positive feedback loops of this kind. Where they become conceptualised in the left pre-frontal cortex, these loops are the basis of confirmation bias: we tend to just seek out evidence that fits the beliefs we already have, rather than challenging those beliefs – and this tendency is the basis of all sorts of other errors.

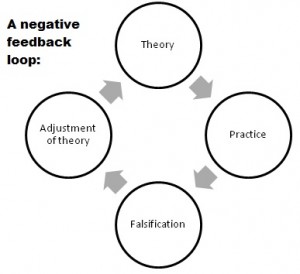

We have good evidence from experience that we are able to move out of such positive feedback loops, by responding to new experiences that challenge our beliefs, and thus adapting our beliefs to fit new circumstances. Instead of a positive feedback loop in which an old habit is reinforced, this is then a negative feedback loop in which learning and adjustment can take place. However stuck in our ways we may be, we have all done this lots of times in the past, especially as children. The human brain retains its plasticity well into old age – and thus we are always capable of changing our beliefs, even if we find the process uncomfortable. To get out of a circular argument, then, or even an addiction or an economic cycle or a cycle of violence, we just need to be willing to learn how to do things differently.

I sometimes think that if this wasn’t called the Middle Way Society, it could be called the ‘Negative Feedback Loop Society’. It’s that basic to what the Middle Way is about. For the extremes avoided by the Middle Way are rigid or absolutised beliefs of a kind that resist change and maintain themselves only in the context of positive feedback loops. In the Middle Way, or as Ed Catmull memorably calls it the ‘messy middle’, we are able to be creative, to switch strategies, to adapt.

Some people are confused by the labels, assuming that a ‘Negative Feedback Loop’ must be bad because it’s negative. But it’s negative only in the sense that it challenges and catalyses change – not necessarily emotionally or logically negative. Similarly, there’s nothing necessarily ‘positive’ in an emotional sense about positive feedback loops: indeed the repression that they often bring with them is likely to stifle any sense of joyfulness and replace it with alienation and boredom in which the energy of possible alternatives is dimly felt but nevertheless denied.

In some formulations of Buddhism (such as that of Sangharakshita), the Wheel of Samsara (which may be interpreted along the lines of such an addictive cycle) is accompanied by a Spiral. A spiral gives graphic expression to the idea that we might continue to go round and round to some degree whilst lifting out of those habits in other respects, and is thus one way of symbolically representing the process of moving out of positive feedback loops and into negative ones. However, the Spiral is often represented as though it was a single absolute path culminating in the transcendent point of nirvana, and on that interpretation, at least, it seems to be incompatible with the Middle Way. Negative feedback loops are a different pattern of judgement, but one that we might find in the thick of a complex pattern of positive feedback loops, and it is the nature of the judgement that is important rather than the ultimate destination.

Positive feedback loops, like samsara in Buddhism, should not be seen as intrinsically bad, but they are limited, and a set of beliefs that rigidly limits us to such loops does then become morally inferior when compared to alternatives that allow us to adapt to a wider range of conditions. We do not need to deduce this from a supposed standpoint of nirvana, or any other supposed absolute beyond experience. It should be clear to us as long as we are willing to simply compare a relatively flexible standpoint to a relatively inflexible one.

I see the nature of feedack loops a bit differently. For example, I imagine positive and negative feedback process occurring in overlapping waves, in great tides of reciprocal adjustment among the elements of a complex system. Multiple causality makes any discussion of feedback difficult, and sometimes I think it’s just easier to think in terms of tides of growth and stabilization, always, shifting around as different elements (e.g., different brain regions) become more or less involved in the “crowd” dynamics…and then falling into attractors, which themselves are shifting around or chaotic or, usually, anything but static.

But I get your general point, and I think it’s a valuable approach.

In fact, I’m fascinated with feedback loops in internal dialogue, or what you rightly refer to as rumination. What powers this incessant cycling of self-perpetuating silliness? Well, silliness at best and misery very commonly. I think that the voices involved in internal dialogue are actual voices, not spoken but having the same properties as voices in actual dialogue. So, what propels dialogical feedback?

It seems that every utterance I make also creates an expectation for a response. And if I don’t get a response from you, I’ll respond to my utterance myself: e.g., why isn’t he listening to me? Then that utterance pulls for a response, and so forth. There’s always expectancy, anticipation, worry, pulling for a next utterance following each utterance we make. And I think that’s exactly what’s going on with the voices in our heads. Our silent voices are making appeals, and arguments, and protests, and there’s a little gap (or not) and some other internal voice (or maybe the same one) says, Well, is that okay with you? Or…Are you displeased with me for that? Or…what can I say that will make you respect me, or like me, or whatever?

So the inner dialogue just keeps rolling along. If there’s one force that we can say is “driving” that feedback cycle, perhaps we can call it “suspense” or the need for resolution. Or maybe, often it gets a little more intense and we can call it “conflict”… There’s nothing like a bit of conflict to keep dialogues, internal or external, rolling on and on, driven by the attempt to win points or resolve concerns.

Hi Marc. I really like the tide metaphor which obviously acknowledges the sheer mind-boggling complexity of brain function. I was also intrigued by what you said about the inner dialogue. It’s funny, we’re so quick to describe people who talk to themselves out loud as ‘mad’, but they’re arguably only doing out load what we’re doing internally. Conflict is also arguably an inevitable aspect of our internal functioning and as social beings. It’s how we deal with it that’s key. We could use a dialectical, integrative process or employ avoidant strategies. In my everyday life, I’m probably more avoidant, especially in conflictive situations with other people, despite knowing that the integrative approach is generally much more effective. I’m working on it though!

The thing about conflict: whether you embrace it, avoid it, or just remain vigilant, it is very often the energy source of our cycling behaviour, either internal or external. Why? Because it keeps the tension going, the necessity for ongoing coping, dealing with, responding to…the opponent (internal or external)….and never getting to a full resolution. It has amazing resilience that way.

That makes sense and you can see why that has an important adaptive aspect to it, at least when we were living on the African plain. I also take your point that it never gets to a full resolution but that’s not to say that external and internal conflict can’t be resolved to a lesser or greater degree. Even if it’s not resolved in many cases, it least in my experience it tends to calm down or dissipate. I can feel really conflicted by a situation with someone in my work situation one day, but be fine in a couple of days time. That’s also often the case even if I’ve not handled the situation particularly well, although the conflictive feelings tend to dissipate more quickly if I do try to engage with the situation in a more thoughtful, reflective way!