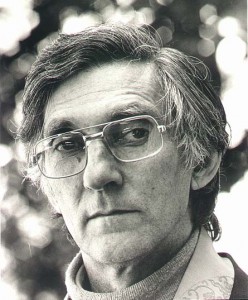

Sangharakshita is the founder of the Triratna Buddhist Community, previously known as the Friends of the Western Buddhist Order or FWBO. Now well into his eighties, he still lives quietly at the new rural Triratna centre called Adhisthana in Herefordshire, in the west of England. As a former member of the Triratna Order, I was once officially one of Sangharakshita’s disciples (though I was always rather uncomfortable with this implication of Order membership). Both before and after leaving the Order, I have been critical both of aspects of Sangharakshita’s teachings and of his status in a personality cult in Triratna. When you have been part of a religious group that you need to distance yourself from, the stakes are high, and there is always a danger of polarisation – people only perceiving a rejection when one attempts a balanced approach. But Sangharakshita is also an important and often inspiring thinker and practitioner in relation to the Middle Way, and I would like to give full recognition to that. I would also like to encourage others to engage positively with his writings whilst maintaining a critical perspective, despite the fact that Triratna does not sufficiently encourage such a critical perspective.

Balanced appraisals of Sangharakshita’s thought are rare. Though you might get some of his disciples to admit to minor criticisms, their public utterances about him are usually characterised by gushy gratitude and uncritical intellectual idealisation. On the other hand, he is largely ignored both by the academic world and by other kinds of Buddhists, many of whom could learn from his ideas, but who are often put off by the cultishness that surrounds him. His writings are voluminous, unsystematic and varied in style (because many are compiled from oral transcriptions, and these are very different from the books he has composed directly), and probably the best overview available is by his disciple Subhuti, Sangharakshita: A new voice in the Buddhist Tradition (Windhorse). One day I hope to write a critical study of Sangharakshita’s ideas of a type that does not yet exist: one that tries to sort the wheat from the chaff. In a blog post, for the moment, I will only be able to say a little about some of the most important of his ideas as they relate to the Middle Way.

First, it must be said that Sangharakshita is probably the Buddhist teacher who has taken the most notice of the Middle Way. It is clear that he has a sense of its importance, and he does often apply it in his judgements about ethical and other matters. For example, he writes: At every stage of the spiritual life we are faced by the necessity of making a choice between either of two opposites, on the one hand, and the mean which reconciles the opposition by transcending it, on the other (A Survey of Buddhism, p.160). That’s probably the reason why, in practice, the Middle Way is often used as a basis of judgement in Triratna: even when the theory surrounding it is so inadequate, people still have a sense of the Middle Way as they encounter it directly in experience and spiritual practice.

However, I say that his theory of the Middle Way is inadequate, as his approach (in common with that of many other Buddhists, it must be said) is to regard the Middle Way as description of a metaphysical truth rather as a method by which to make judgements in our experience. He sees the Middle Way as having metaphysical, ethical and psychological modes, but his account of the ethics and the psychology is deduced from the metaphysics he assumes. As a result he ends up caricaturing the extremes to be avoided in a way that is quite inadequate to our experience of the complexity of our beliefs and the way they relate to psychological states. He writes: “The belief that behind the bitter-sweet of human life yawn only the all-devouring jaws of a gigantic Nothingness will inevitably reduce man to his body and his body to his sensations; pleasure will be set up as the whole object of human endeavour, self-indulgence lauded to the skies, abstinence contemned, and the voluptuary honoured as the best and wisest of mankind.” If, on the other hand, one believes in an Absolute Being such as God, “the object of the spiritual life will be held to consist in effecting a complete dissociation between spirit and matter, the real and the unreal, God and the world, the temporal and the eternal; whence follows self-mortification in its extremest and most repulsive forms” (Survey pp.162-3).

If the Middle Way is to be of any use to us, it cannot merely consist in such a caricature of the materialist, the Marxist, the Christian etc, with the automatic assumption that, because of traditional statements about the Middle Way found in traditional Buddhist texts, these people must either be totally self-indulgent or self-mortifying. Experience suggests rather that the relationships between metaphysical beliefs and psychological states are far more complex than this. There are self-mortifying Marxists and self-indulgent Christians, for example. The Middle Way potentially offers far more insights than this caricature of it suggests, but it will only yield them with an approach that avoids metaphysical assumptions about the Middle Way itself, and takes experience rather than obscure dogma as the basis of judgement about how beliefs relate to psychological states.

It is this metaphysical reading (of a principle that needs to start with avoidance of metaphysics) that I assume leads Sangharakshita to his view that the most basic principal of Buddhism is conditioned co-production (or dependent origination) – a claim about how things are rather than a method of investigation. So despite his emphasis on the Middle Way in some respects, Sangharakshita’s approach merely promotes confusion about it in other respects, because the Middle Way as an experiential method gets constantly confused with a ‘truth’ that conflicts with that method. This confusion can only have a negative practical effect when people try to put the Middle Way into operation.

However, there are many other useful ideas and attitudes that I owe to Sangharakshita. One is his universalism – not in the shallow sense that all views are equally good, but in his conviction that all kinds of traditions can be mined for insights that support and inspire the practice of the Middle Way. For example, he is a lover of Renaissance art and of William Blake, as well as attempting to find common insights in all the schools of Buddhism and even in some aspects of other religions.

Sangharakshita has also made considerable use of Jung’s thought and related it to the insights of Buddhism. He makes use of the concept of integration and a psychological explanation of what is involved in spiritual development. He also makes excellent and stimulating use of Jungian archetypes in his discussion of the deeper significance of Buddhist scripture and symbol and its significance. As a result, Triratna Buddhists tend to make widespread use of archetypal interpretations of religious forms.

Sangharakshita also points out the dogmatic nature of group thinking, and recognises a Middle Way between groupishness and individualism. This is what has led me into the conclusion that the function of metaphysical belief is the maintenance of group loyalty. Sangharakshita instead extols what he calls ‘the true individual’. In effect this seems to mean a person who follows the Middle Way in developing an autonomous judgement, neither prematurely accepting nor rejecting the group and the beliefs that give it identity.

Sangharakshita is also undoubtedly inspiring as a practitioner, who has tried to combine an intellectual articulation of Buddhist insights together with huge commitment to its practice. Though it is often rather difficult to separate genuine experience from hagiography in the accounts leading disciples give of his practical acuity, it is obvious that he has engaged deeply and seriously with both meditative and ethical practice. His ethical writings and guidance have given a particular emphasis to the practice of friendship that seems to have been particularly helpful in the development of Triratna, and marked it out from other Buddhist groups.

This commitment to the unity of theory and practice just by itself is both inspiring and rare, particularly when one considers that the theory Sangharakshita has developed is what he has thought out for himself rather than merely adopted uncritically from tradition. I only wish that Sangharakshita’s disciples would emulate their teacher more in this respect, by treating Sangharakshita’s own thinking with the critical attention that a full respect for it merits, rather than treating his words and writings as a new basis of uncritical authority. To follow Sangharakshita, surely, one should try to do what he did, which was to critically appraise the traditions that he found in his context, and, where necessary, start afresh to develop new approaches that better capture the insights one finds in past work. To turn Sangharakshita into a guru, as even he at times has suggested is not appropriate, seems to me like a betrayal of the best that can be found in his legacy.

Related pages

The Buddha and the Middle Way Audio

The Middle Way in Buddhism Books