Integration can apply just as much at the socio-political level as at individual level. At both levels, similar conditions apply. There are competing desires that gain dominance at different times, both in the individual and in wider society. Those desires are attached to beliefs representing the world in which the individual or society is moving. Those desires can continue to vainly compete, each with incompatible beliefs, or they can move into more appropriate beliefs and integrate. Just as the two mules can fight or integrate, so can two nations – and indeed, the mule pictures were originally created by pacifists and labelled ‘a fable for the nations’.

The desires held by groups or societies are always simultaneously the desires held by individuals. A clash between groups, even on the scale of world war, is nothing more nor less than a clash of desires. This offers a crucial insight: whenever you get into conflict with someone else, you are not fighting them as an individual, but rather fighting their desires. In a conflict of desires, indeed, there can be no enemies. This is one of the key insights of Gandhi, who directed his campaigns towards persuading his opponents rather than defeating them.

There are, of course, also differences between the integration of the individual and of society. Generally, however, it is the similarities that are under-appreciated, because of our resistance to recognising that we may not be single selves, leading to a preference for thinking of ‘me’ as one self in opposition to other selves. The constant pressure of the ego is to maintain the belief in a single self, which assumes that we are already integrated, and that it is only society beyond us that needs integrating. This can only be described as a massive delusion. Of course society does need integrating, but so do we as individuals.

Those who have compared the individual to a city, with different competing citizens, have often been considered rather fanciful. However, the likely accuracy of a view of ourselves as plural is confirmed not only by the observation of psychological disorders (such as multiple personality disorder) in which selves are identifiably separate, but by psychoanalysis, by conflicts between the two brain hemispheres, and by the crucial role of metaphorical constructions in meaning under the embodied meaning thesis (showing that there is no single ‘correct’ metaphor under which we work). If the individual is like a society, then, the society is also like an individual. The macrocosm (society) can be constantly compared to the microcosm (individual).

The main difference between the processes of integration of the individual and society is just that the process in society has a further level of complexity. Desires in society may be pursued by individuals, or by groups of varying sizes, all competing with each other. Groups can exist at different levels, from the family unit to the nation state, and larger groups may consist of hierarchies of shifting sub-groups. A degree of integration in a larger group is dependent on that of sub-groups, which is in turn dependent on the integration of individuals.

To make this situation even more complex, we are all members of many different groups. For example, a male middle-aged Sikh physics teacher living in Birmingham who is married with a family and likes model railways, is a member the group of males, the group of middle aged people, the local, national and international Sikh community, the group of teachers, the group of physics teachers, the group of Birmingham residents and also residents of his specific neighbourhood, the group of British citizens, the group of his immediate and wider family, the group of husbands, the group of fathers, and the group of model railway enthusiasts. These are just formal groups: he may also have informal groups of friends, or be part of further online social groups. All that is required to make one a member of such a group is identification with it.

Any of these complex groups that we are part of may be more or less integrated, insofar as the desires of the members are compatible or incompatible in relation to the group. They will only be compatible to the extent that the relevant beliefs are shared. So, for example, if teachers are divided over whether to go on strike about changes to their pension scheme, this means that the group of teachers has different beliefs about justified action in the situation, and because of these different beliefs, like the two mules, they are tugging the group of teachers in incompatible directions.

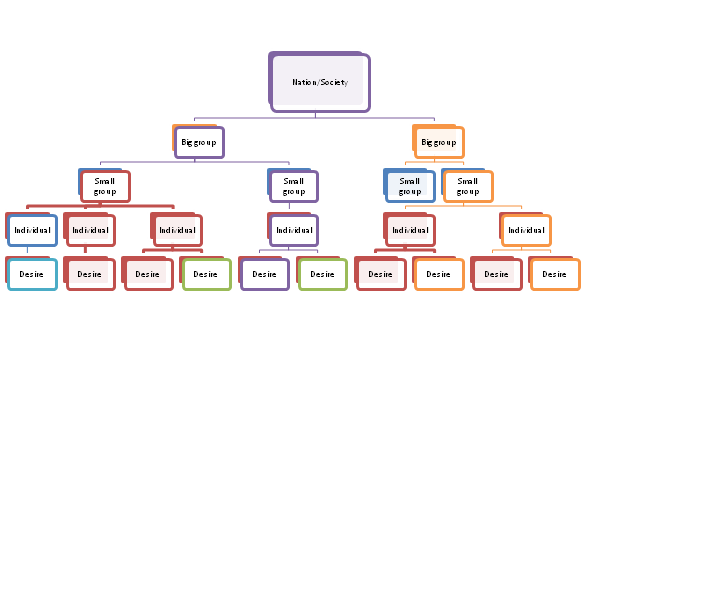

To think about the integration of groups within a wider society or nation thus potentially brings in enormous complexity. Not only will these be competing desires, with some dominant over others, in that society as a whole, but some of these desires will be dominant in big groups and smaller groups within that society. These groups in turn will be composed of individuals who each have competing desires within them, some of which will be dominant at a given time and others repressed. The desires that end up dominating in the society as a whole will be those of certain individuals, who manage to get their desires to dominate smaller groups, which dominate bigger groups, and so on. The diagram at the bottom gives a simplified schematic view of this situation, in which the colours represent types of view. The purple desire has ended up dominating the whole society in this case, even though only one individual on the diagram holds that desire (and even he/she is also repressing other desires).

Nevertheless, we may need to integrate conflicts at a social and political level, even if we are only able to do so crudely, in order to address them effectively at an individual level. Most of the desires held by individuals will be ones understood and articulated in relation to groups. For example, the individual may have a desire for better rights of fathers for custody of children in divorce cases, or a desire for electoral reform, as well as a desire for pudding or a desire for sex. Even something as basic as a desire for sex will nevertheless by mediated by social models and expectations.

Given the amount of complex interplay between our desires at individual level and at social level, we have no option but to engage in integration at both levels simultaneously. There is no choice between individual and social integration, for neither is likely to get very far without the other. We need our outer Gandhis to bring integration to a political conflict, but we also need an inner Buddha to confront the shadows within ourselves with insight, compassion and resolution.

(Click on diagram to enlarge)

Picture: President Bill Clinton with King Hussein of Jordan and Yitzhak Rabin of Israel, signing of peace treaty (Wikimedia Commons).