I am sometimes asked whether Middle Way Philosophy offers a meaning of life, and what it has to say about death. I have often been hesitant in trying to offer perspectives on these kinds of questions, because there is such a long tradition of unhelpful metaphysical speculation about them. However, I think the Middle Way can be applied helpfully here, if only to challenge that tradition of speculation and point us back to experience. This post is the final chapter of my new introductory book, Migglism, which should finally be published within a week or so now. I have added it to the book recently in response to a useful suggestion from Mike Fedorski.

If we are to avoid metaphysics, there can be no meaning to life as a whole beyond the meaning that we experience. That may sound like a familiar truism – that the meaning of life is just what we make it. However, the Middle Way implies a couple of other points here as well. Not only is there no absolute metaphysical meaning to life, but there is no denial of meaning either – life is not meaningless, but rather full of the meaning we find in it. The other crucial point is that meaning is an incremental matter. We are not going to find meaning all at once, as a solution to all our struggles to find meaning. Rather, we can gradually increase the meaningfulness we encounter in life.

I suggest, also, that this incremental meaningfulness is found with our degree of integration. The meaning and value we find in life as a whole, after all, need be no different from the meaning and value we find in different specific things in life: for example, the momentary value we find in stroking a pet, or embracing someone we love. The problem with getting a meaning of life as a whole from these experiences is not that they are not meaningful in themselves, but that this meaning is momentary, and perhaps in conflict with the lack of meaning we may experience at other times. When I’m feeling frustrated in the office later on, the embrace of the early morning is already gone from my awareness.

Thus it seems that we should gradually find more meaning in life the more we become integrated, whether that integration is of desire (bringing our energies together), meaning (bringing our sense of significance together), or belief (bringing our views of the world together). The more we are integrated, the less likely we are to be caught up in inner conflict and frustration, and thus the more likely we are, on average and on the whole, to find life unified, meaningful and fulfilling.

This fulfilment is always relative to the circumstances we find ourselves in. If, for example, you are a citizen of Aleppo being constantly bombed by Syrian government forces during the Syrian civil war, you will spend most of your energy just dealing with extremely difficult and stressful external conditions. However, there will still be more or less integrated ways that you can respond to these conditions. The meaningfulness of your life in such circumstances could only really be measured against what it might have been in different circumstances, whether those circumstances were reasonably secure or even over-protected – not against some abstract absolute. Some people can be destroyed by difficulties, while others gain an intense sense of fulfilment by responding in an integrated way to them.

One of the basic conditions of difficult circumstances in life is the ever-present threat of death. Like other conditions in life, it seems that the key question is whether we can accept death and respond to it in a balanced way, rather than anything about death itself. Speculation about death itself is just a distraction from the Middle Way – whether such speculation involves beliefs about an afterlife (or reincarnation), or the denial of such beliefs. Our living experience gives us no purchase at all in justifying either affirmation or denial of afterlife beliefs, so, for example, the amount of debate about rebirth that distracts Buddhists who are otherwise interested in practising the Middle Way is rather unfortunate.

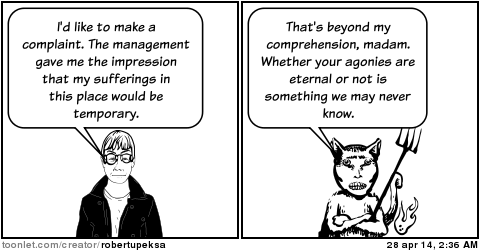

Death itself seems to be just a condition of life. It is something we are often inclined to forget that it is the temporariness of our living experience that makes it meaningful to us. An eternity of pleasure could be no more meaningful to a breathing, changing creature than an eternity of suffering, as we can only grasp the idea of pleasure or suffering in relation to an experience in which things change. The idea of such an eternity is thus just a symbolic abstraction. In practice, our pleasures are pleasurable and our pains painful only because they are impermanent, and the same could be said for life as a whole.

So, death is just a condition of life. It may be one that causes us anxiety, but anxiety is just another term for conflict between a part of us that is attached to living experience and a part that recognises the inevitability of death. If we can still that conflict, through integrative practice of one kind or another, there seems to be no reason why we should not make progress in stilling our fear of death.

I understand the sentiment that leads Dylan Thomas to write

Do not go gentle into that good-night,

But rage, rage against the dying of the light!

I read his poem as a protest against passivity and morbidity. It is possible to be too passive in the face of death, or too obsessed with the question of death. If we swap the immediate experience of living for a mere abstract idea of how we might adapt to death, we are merely distracting ourselves from the full use of the life that is available to us. However, I think Thomas’s mistake is to identify the acceptance of death with one partial feeling we have in life. Instead, I think acceptance of death probably comes through integration of our different desires in life. We do not have to fight against our fear of death, but rather incorporate the energy of that fear into an overall recognition that we can live life better in a full acceptance of its conditions – and those conditions include death.

Hi Robert,

Sometimes I think of the process of dying more than death itself, I hope it will be dignified but there is no promise that it will be, such thoughts may be inevitable at the age I have reached. I am eighty one, much to my amazement, friends of my age wrote jokingly on a recent birthday card, ‘we’re still here then!’ There is no point worrying about a future date that will certainly arrive, it cannot be too distant now.

I shall be sad to leave this life that I lead, it is happy on the whole, not that life has always felt so good. When I see family and friends and when I potter in the garden I think to myself, ‘I’ll miss you’ but of course I will not be around to miss anything, nor do I consider that I will be entering another kind of existence, that is beyond my experience to know.

I think Robert’s essay on death is a very sensible one, and I’m in complete agreement with everything he says. As I’ve said several times elsewhere and here, I’ve gained enormous reassurance from the extensive (but second-hand) experience of death, and how others face it, over fifty years of nursing work. I can’t account for the way people adapt to the knowledge that they are dying, and the equanimity with which they ‘come to terms’ with the process as it moves to its ultimate end. I don’t see (perhaps I’m insensitive or blinkered) that people who have a formal practice ‘do death’ any more skilfully or (dare i say it) more successfully than people who have never given it much serious thought. It just seems to me that the process (whatever it is) embraces people, and they seem to submit to it, wisely and graciously.

There may, as Robert says, some wobbles along the way: anxiety, confusion, a sense of helplessness, and anger; and these human feelings are what one would expect. A few words of reassurance can go a long way to helping people steady themselves, and a sense of humour often helps where solemnity can strike a discordant, incongruouus and less-than-helpful note.

I’m struck by the mysterious subtle potency (as I see it) with which knowledge of the certainty of death seems to visit people I’ve known and cared for, and with the associated mystery that people very seldom explicitly acknowledge to others that they know they are dying, although they do – at least in my experience – convey their receipt of the ‘unmistakable tap on the shoulder’ to receptive others in wordless ways; ways that it is our privilege to be gifted with, and which inspire our own reflections on death, and mitigate its sting.

Like you Norma, I’m aware most days of the imminence of my own death. I liked your elegy on dying. I don’t know how much store you set on dignity, or what it means to you. Dying usually means you lose control of your functions. Because that’s inevitable, it’s just a matter of letting its importance (control) fall away, like the rockets on a space ship when it has escaped gravity. As I mentioned above, it seems ‘natural’ to let go, and rely graciously on others to help, where help is available. Fortunately for those of us who live in developed civilisations, help is usually at hand.

I drove to the supermarket today, and I was vividly aware that the moment when I was preparing to get out of the car with my shopping bags could easily, prosaically, and simply be my last. The world will go on, the check-outs will bleep, the shelf-stackers will stack more boxes of Budweiser, and my wife and children will face some initial shock and turmoil, which will eventually subside. The Middle Way Society will announce my death and probably write a few kind words of recollection. Thank you in advance!

We recently adopted three ten-month-old kittens. They are now well settled in to our home. I’m aware that they are very likely to outlive me, perhaps by as many as ten years, possibly several more. They’re very nice pussies, and seem very happy to be free and to look up at the sky..

Hi Robert (and sorry as this is an old topic, but it is an important one.)

I can understand your reluctance to tackle this subject, as hard agnosticism about what happens (or not) after death – my death, everyone and everything’s deaths – might be the single hardest application of a Middle Way approach. Not only are we regularly bombarded with the ‘certainty’ of people who supposedly know more than us in whatever field they’re an expert in (but let’s take physics as a notable example), making any degree of attempted agnosticism often heinously difficult, I’m not entirely sure that the question of what happens (or not) after death can be so easily bracketed. Given that we appear to be goal-directed beings, what we believe about death, even unconsciously, plays a larger role than we care to admit, I think.

It’s fair to say that the life of someone who holds an annihilationist view, for example, may not have the same kind of motivational force (or degree of motivational force) of someone who believes this world is just a preparation for another, for example, unless, say, they have a conception of time different to the one we personally experience (in which case we’re back into the spiral of metaphysical speculation).

While this post is enlightening, and I’m not disagreeing with what’s written – just throwing some ideas into the ring – I’d personally argue that it’s less the event of death itself that people fear than what this event means for our lives in the here and now. If we truly live by hard agnosticism on this subject, do we really have less of a clear focus in life than someone with concrete ideas about it?

*Correction: MORE of a clear focus in life, not less.

Hi Laurie,

Thanks for reviving this topic. I don’t know if you’ve had a look at the book this blog post was taken from (Migglism), but you might find it helpful to consider this question in relation to the wider arguments in that book: there’s a page about the book on this site http://www.middlewaysociety.org/books/middle-way-philosophy-books/migglism-a-beginners-guide-to-middle-way-philosophy-by-robert-m-ellis/. I say this because the effects of hard agnosticism are part and parcel of the practice of the Middle Way itself, and thus need a wider explanation. To put it briefly, the acceptance of any metaphysical belief involves absolutisation, which represses alternative perspectives and thus interferes with the integration process. If that point is relevant to other areas of our lives, I don’t see how our attitude to death could be an exception to it. Indeed, if anything, the moment of death seems to be the ultimate test of one’s degree of integration.

That’s not to say that people with beliefs either for or against the afterlife may not also be integrated to a fair extent, as any one particular belief like this has a wider context that includes more practical beliefs (see other posts on here: ‘Franciscan Saintliness’, ‘An Acre of Forest’, ‘People and beliefs’). My argument is that saints who accept death with equanimity do so because of a lot of practically adequate beliefs rather than because of their absolutizing beliefs: in other words, despite their belief in the afterlife (and other associated beliefs), rather than because if it.

When I first started developing Middle Way theories from a Buddhist starting point I used to talk about ‘annihilationism’ (or ‘nihilism’), along with ‘eternalism’, but I no longer find these useful concepts, because they require us to believe in a cluster of negative metaphysical beliefs that must always go with each other (and a closer look shows that they don’t). Those clusters may have represented a common pattern in the time of the Buddha, but they no longer do. For example, denial of the afterlife no longer necessarily goes with denial of karma or similar cosmic justice beliefs, nor necessarily with moral relativism. There are plenty of counter-examples that show the traditional Buddhist analysis of ‘eternalism’ and ‘annihilationism’ to be an over-simplification: e.g. Marxism, which has absolute beliefs about the final good for humankind but will also deny afterlife beliefs.

Instead, I think we need to take metaphysical beliefs one at a time. They do come in opposing pairs (positive and negative) and they do tend to create mutually supporting clusters. But those clusters don’t necessarily involve beliefs about the afterlife interacting with other metaphysical beliefs. Some people today just don’t think about the afterlife at all for the most part, but still have plenty of other dogmas: e.g. hedonism, managerialism or absolutised political or economic ideologies. I think world religions are often in the habit of over-estimating the significance of afterlife beliefs, but in the end they are just one possible kind of metaphysical belief among many. All of us will have some such metaphysical beliefs along with other more adequate beliefs, and the issue is how they contribute to the complex picture created overall by our habitual and embodied beliefs – many of which are largely unconscious models that do not, and could not, have anything to do with absolutisation.

Robert, you wrote: “Indeed, if anything, the moment of death seems to be the ultimate test of one’s degree of integration”.

Even in the context of the other comments you made on this topic here, I don’t quite understand what you mean by “the ultimate test” of one’s degree of integration.

Do you suggest that, at the moment of death, we are aware of a test or challenge (arising where and how?), and that some reckoning occurs at that time, and that the result of that reckoning, and of its finality (its ultimacy) is simultaneously in our awareness?

Or am I being too pedantic?

Peter

Hi Peter,

By the ‘ultimate test’ I didn’t mean to suggest any external criteria to test us. What I meant was just an extension of the point that generally when we’re most under stress, it’s hardest to respond in an integrated way. Death seems to be the ‘ultimate’ stressor, in the sense of the final one in our lives. But, of course that doesn’t mean that people can’t rise to the challenge, or that there may not be other processes at work that help us to accept death.

Thanks Robert. Before I read your comment I lay in bed pondering my question. I “saw” that the question I asked (and my confusion over what you wrote) was based on a false assumption that an ultimate test must have ultimate consequences, and would be applied with consequences in mind; in other words my understanding of ultimate in the context of death was packed with unexamined, and unhelpful because irrelevant, metaphysical meanings.

Under closer scrutiny, it makes sense that my last thought would be susceptible to a simple test of my state of integration at the time the thought arose, in the same way that it would be susceptible to the test “Is this Peter’s last thought?”

Thanks for that.

Hi Robert, thanks for replying.

So as far as I understand it, the Middle Way appears to be saying that metaphysical beliefs and practical beliefs operate on a two-tier system, but the widespread assumption that the latter can only come from the former is incorrect. Is this right?

By and large, I agree with you when you say that approaching death – particularly in the final moments – is the ultimate challenge for us when applying a Middle Way approach. I just personally find complete and total agnosticism on the subject very, very difficult, and metaphysical speculation plays a very deep-seated and insidious role. I’m no fan of Heidegger, but I do think he was correct when he saw death as something that forces a response from us, and gives life a shape that can be construed positively or negatively (as the amount of philosophy dealing with feelings of futility can attest to). These varied responses it has elicited throughout history have largely been down to people making their minds up on what happens afterwards and acting accordingly, and this is an on-going phenomenon: those wholly convinced of the non-existence of an afterlife may be investing huge sums in life extension technologies, or those who believe in a particular version of one may be jihadist suicide bombers, etc. Total separation of what happens in life from what may or may not happen after death would seem to have few historical precedents, if anything.

Of course, what we believe about death has no bearing on its actual – we will die regardless of what we believe about it beforehand. Therefore the question is not really about death, but what it means for our lives. How can this meaning be truly separated from afterlife beliefs, or their denial, as you suggest? Can you elaborate any further on this?

Apologies if it seems like I’m not fully ‘getting it’ yet. I can see why you’ve put this subject at the end of the book – it could be that I’ve just jumped straight to it without immersing myself in all the primers.

Hi Laurie,

Yes, I agree that there is a kind of ‘two-tier system’, but only in the terms of metaphysics itself. Also that the metaphysical beliefs are formed in their own terms rather than justified by practical beliefs. But there need to be several qualifications to avoid potential misunderstandings of such statements. One is that all meaning comes from practical, embodied experience (i.e. the right hemisphere): it’s just the assembling of metaphysical propositions that are claimed to have a truth-dependent meaning that occurs independently in the left hemisphere. When the left hemisphere becomes too over-dominant it starts to assume that it is autonomous, that meaning should be understood in its purely denotative terms, and that’s how the ‘two-tier’ system emerges in its own construction. The widespread assumption that meaning is purely truth-dependent and thus that metaphysical claims even make sense depends on the over-dominance of the left hemisphere. But beyond that delusion created by the metaphysical mindset, all meaning depends on experience, and there is no two-tier system. Here the left hemisphere simply contributes to wider system of integrated meaning and belief.

I agree that total agnosticism (of any kind, not just on death) is very difficult (if not impossible) in practice. It’s easier to adopt it as an intellectual principle than it is to identify every metaphysical assumption in practice. It’s an ongoing process, not just an intellectual position. I don’t expect to become totally agnostic any more than I expect to become enlightened, but nevertheless agnosticism is an important principle.

I meant something like the Heideggerian perspective here when I said that “death itself seems to be just a condition of life”. Like you I’m not really a fan of Heidegger, but like any other thinker he has his insights.

As to how we can make progress in separating the meaning of death in our lives from afterlife beliefs (or their denial), I’m not sure than can be separated from how we make progress in developing integrated beliefs in general. Afterlife beliefs v their denial are closely associated with cosmic justice beliefs v their denial, which in turn are often associated with realism v idealism about phenomena, absolute beliefs about the self or its absence, and absolutist v relativist moral beliefs (see more about all these beliefs and the issues around them in ‘Middle Way Philosophy 4’). As I wrote above, metaphysical beliefs tend to come in clusters, but they’re not always the same clusters.

To engage with the underlying process creating the clusters we need integrative practices. Meditation and similar practices can help produce basic integrative conditions. The arts can help to provide meaningful archetypes than can feed our whole experience without recourse to metaphysics. Critical thinking and objectivity training can help us recognise metaphysical beliefs and absolutizing biases, so as to help avoid them in judgement.

In relation to death, I’m particularly struck by the role of the arts. Reading Dante’s Divine Comedy, for example, is on the surface all about afterlife beliefs; but when read with sufficient awareness of its archetypal value and a separation from metaphysics, it can help us engage with the underlying meanings that have become associated with afterlife beliefs. Dante is only one of many artistic engagements with the afterlife and its significance, but Dante in its turn it has created a tradition of further exploration of the same themes in visual art, theatre and so on.

I think I understand a little more clearly now, thanks.

Regarding the arts, one of the reasons I ended up reviving this topic was after reading Larkin’s ‘Aubade’, which demonstrates very well the (ugly) consequences of absolute denial of afterlife beliefs. Larkin’s whole worldview seemed to culminate rather sadly in this poem. I was struck by its sheer provocative power as poetry, but also suspected it’s fuelled by some of the faulty thinking the Middle Way tries to avoid. Undoubtedly while there is helpful assistance towards integration to be found in the arts, there is also much that is unhelpful in this way. I think we can all tend towards the Larkin mindset at times – almost bloody-mindedly refusing anything other than absolutizing beliefs.

I agree that ‘Aubade’ reflects that unhelpful mindset: one that focuses only on the ‘facts’ and neglects our role in interpreting them. “Nothing more terrible, nothing more true.” But at the same time it communicates what it is like to be Larkin in that mental state, and in the process makes that mental state meaningful to us. It’s only by recognising such states and integrating them that I think we can make much progress in relation to issues like this one: and there it is often helpful to focus on the meaning of works of art rather than the beliefs that we think they convey.

Sorry for dragging this one up yet again…But two things.

First is: while I’m not suggesting that the integrative process you describe is instantaneous, or a mere quick-fix ‘sticking plaster’, might the Middle Way be applied in the moment, to invasive, unpleasant thoughts that, in the case of death, can become debilitating at times?

A common one I (and innumerable others, undoubtedly) have had in the past is something along the lines of “if my subjective experience now is all there is, that experience is a product of my brain, and, when my brain is destroyed at death, the sum total of my subjective experiences is lost forever, why am I bothering right now? When I am dead, I will not know whether I ever lived, just as before I was born I did not know whether I ever would live.” This is a thought that relates to what death means for our lives, as I brought up earlier. It’s also a painful one.

Now, of course, it’s a thought with a host of metaphysical assumptions at work. Identifying them:

1) I’m assuming my subjective experience is all there is – in a ‘self’, essentially.

2) I’m assuming there is a ‘sum total’ of experiences.

3) I’m assuming all my subjective experience is a product of the brain.

4) I’m assuming that all my subjective experiences will be lost when I die.

5) A big one: I’m assuming that I shouldn’t bother with anything based on the other metaphysical assumptions. There’s a definite reaching for a absolute, God’s-eye perspective that applies ‘eternally’.

6) Maybe even something about linear time, as it is experienced.

My usual approach in the past has been to merely replace these metaphysical assumptions with new, maybe more hopeful ones (maybe, as many a scientific naturalist has implored those who don’t like the ‘facts’, ‘invent a new physics’. But the Middle Way warns against this, and I agree. From past experience, it sets you onto a spiral where too much of a stake is placed on these assumptions being the right ones, and uncertainty becomes uncomfortable and decidedly non-integrative.

Once metaphysical assumptions have been identified, what is the next practical step in a moment-by-moment application like this?

My second issue: one of the major difficulties is that the metaphysical assumptions above that we would identify as such also happen to be scientific orthodoxy. I’ve read your page on Naturalism, and your criticisms of it (and recommendations of Pyrrhonian scepticism) make perfect sense to me – but it does leave us in the difficult, and lonely, position of supposing that the majority of scientists are somehow wrong-headed in what they do. Most of them, of all stripes, will be fairly clear on what death is – though far less so on what it means for us. I suppose this is my difficulties with true agnosticism spelt out in detail: I still respect and trust science, to the point where its preferred outlook – Naturalism – is still more likely to inform my beliefs about death than afterlife beliefs. Its authority in my mind is quite deep-seated and will be difficult to dislodge.

If the above all seems garbled and unintelligible, then apologies in advance. I’m just keen to investigate the in and outs of the Middle Way on this subject at the moment.

Hi Laurie,

I’m really appreciating these searching and important questions!

With your first issue, apart from the metaphysical assumptions you list, there seems to be a bigger assumption behind your question “why am I bothering right now?” That’s a rhetorical question that seems to be another way of saying “given these conditions, my experience is not meaningful or valuable.” I would really question that. The meaning and value of your experience during life does not depend on your beliefs about any of these other issues. The only real reason for considering them intellectually at all is to recognise their irrelevance and move on. If life does not seem meaningful and valuable, I’d suggest that’s a psychological issue that needs to be addressed psychologically through integrative practices. I’d agree that just being agnostic about the philosophical questions doesn’t by itself resolve any psychological issues: it just provides a basic condition for letting go of them and moving on to more important matters.

On your second issue, I’m not sure I agree that most scientists are ‘wrong headed in what they do’. What they do as scientists is largely dictated by scientific procedures that get a lot of social reinforcement, and of course some of it consists in genuine exploration. It may be the case that the majority of scientists have a naturalistic “Death is the end” view, but that naturalistic interpretation is probably a pretty small part of what motivates them (just as Christian dogma seems to me a very small part of what motivates the most admirable Christians). Then, when they actually encounter death, I’d expect the actual attitudes of scientists to vary quite a lot, between terror of annihilation at one extreme and agnostic equanimity at another. It depends very much both on their personal integration and how they choose to interpret the idea that “death is the end”.

I agree with you in respecting and trusting the science, though at the same time I think we have to bear in mind its limitations. I have no reason to develop positive beliefs, even provisional ones, that actively contradict the naturalistic views that experience depends on the brain and that that experience is likely to cease when the brain cease to function. But it’s how we feel about that likely situation that is far more important than such views about the probabilities: and terror of annihilation as a response just seems to be dependent on a very narrow, dogmatic view of who ‘I’ am – one that needs to be gradually let go of.

Hi Robert, sorry for the late response here – your reply was registered, I’ve just spent a while chewing it over.

I agree that every idea about death can come with a myriad of responses. It seems to come down to the person, unfortunately. Both the fixation on these unanswerable questions, obviously beyond experience as you point out, and the emotional states that follow from possible ‘answers’ to them seem to constitute an obsessive-compulsive complex in many, that I probably have to quite a severe extent.

For example, if I get a certain idea, word, or phrase that produces a negative reaction in me, then I feel I ‘have’ to pursue it in more detail by running it through a search engine, reading endless articles, comments and general ‘internet noise’ on the subject, and overall feeding and entrenching that habit. This is why Middle Way integration as you describe it might be a tough business. It’s one thing to know you’re doing it, quite another to put a stop to it.

I should mention, but you’re probably aware, that a lot of philosophy (often contemporary) is in the dubious business of abusing facts and values and encouraging harmful reactions to abstract ideas, for example surrounding death – this is something I’ve commented on over at David Chapman’s ‘Meaningness’ site on a few occasions, as he does a similarly excellent job of critically examining this issue. Your approach and his are very different ones to what seems to be a common problem, but both are extremely helpful.

Hi Laurie,

I agree that changing our mental habits is a tough call. It can only be done gradually and in a full and realistic acknowledgement of where we start. But there are also grounds for optimism. One is to reflect how much we have already changed from where we started when we were younger. Another, more generally, is brain plasticity. I was particularly moved by an account in Daniel Siegel’s ‘Mindsight’ of how he worked with a 92-year old man, whom he managed to help get out of some rigid rationalised attitudes and greatly improve his marriage relationship. It’s never too late!

Another reflection that perhaps might help here is that our obsessive tendencies are not entirely negative: it’s a question of how we direct them. The over-dominant left hemisphere sometimes gets passionate about unhelpful things, but it can also get passionate about integration with the right hemisphere. I’m pretty obsessive myself, which for example has sometimes led to a rather compulsive relationship with computer strategy games: but I find the best way of dealing with that is to pour my obsessiveness into Middle Way Philosophy. One shouldn’t be under the illusion that maintaining ideas about integration is the same as becoming more integrated, but the more deeply one engages with integrative ideas, I find, the harder it becomes to ignore the conditions that integration requires. Another way of putting that (found in Buddhism) is that wisdom is merely well-channelled hatred.

Hi Robert, something else came to mind with this topic.

What are your views on Terror Management Theory?

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Terror_management_theory

Is it an accurate psychological model? (I would say maybe, up to a certain point.) Is it a helpful one? (I would say no, quite the opposite.) But what do you think, in a Middle Way context?

My immediate thought about this is that it needs to be put into the wider context of integration. If we experience a conflict between a desire to live and a desire to recognise the reality of death, that’s an integration issue. That’s not to say that the solutions suggested here are wrong or always ineffective, but they seem to have too narrow a focus. That may particularly cause problems if the solutions are not integrative in a wider sense: e.g. if ‘Terror Management’ takes afterlife beliefs to be an acceptable solution to terror about death rather than a distraction that replaces terror about death with other kinds of psychic conflict.

The approach seems to take this conflict created by terror of death to be inevitable, which I would question. Granted, this recognition of death is in conflict with a ‘desire to live’, but what is a desire to live? A desire to live for how long, with what assumed identity, in what context? If our views about ourselves become sufficiently provisional, as a result of integrative practice, we can continue to want to live, but want to live for a length of time that we recognise to be limited. We may want to live to complete a certain project, say, or to support another person, but then become much more accepting of death. We can want to live now, but also accept that there will be other times when we will no longer want to live. That’s all about recognition of our changing states over time, which is integration of the assumptions of the left hemisphere through the operation of the right.

Yes, these are similar thoughts to mine.

The intellectual framework behind TMT research is largely influenced by Ernest Becker’s ‘Denial of Death’, which is a lucid piece of work in describing some of the age-old conflicts we’ve been discussing here, but makes the fundamental assumption that every human being’s default reaction to death is the same, all of the time: horror, terror, dread, etc, hence the supposed need for distractions and symbolic placebos. Reality is assumed to have a standard that is assumed to be inherently alienating and terrifying. It certainly CAN be…for vastly different people at different times. As someone prone to that view myself, however, I’m still wary of pathologising the entire human race, or assuming that particular mental state is something that’s always with me, always has been as and always will, ‘unconsciously’ or not. This is where I’m finding Middle Way philosophy

particularly helpful.

(I’ve always strongly disliked the ethos behind many Woody Allen films for the same reason as above. Allen himself, and his character surrogates, seems to reduce all of the happiness and meaningfulness he evidently finds in life down to a distraction technique, because he knows things can’t last forever and that is treated as a threat. I suppose from a Middle Way perspective, this an example of harmful absolutising in the arts.)